Archive for the ‘Syriac manuscripts’ Tag

CFMM 167 and 165 (in that order) are two small notebooks from the late 19th or early 20th century. There is no explicit date, nor did the scribe give a name, but the writing is very clear. Included in the collection are some of Jacob of Serugh’s homilies against the Jews (№№ 1-5, 7, so numbered); this cycle of homilies was edited by Micheline Albert, Jacques de Saroug. Homélies contre les Juifs, PO 38. There are also a few other homilies, the most important of which are the first four copied in CFMM 167, all of which have never been published, although they are known from the Dam. Patr. manuscripts and from Assemani’s list of homilies in Bibliotheca Orientalis I: pp. 325-326, no. 174 = the second hom. below. (For a list of incipits of Jacob’s homilies, see Brock in vol. 6 of the Gorgias edition of Bedjan, The Homilies of Mar Jacob of Sarug, [2006], pp. 372-398.)

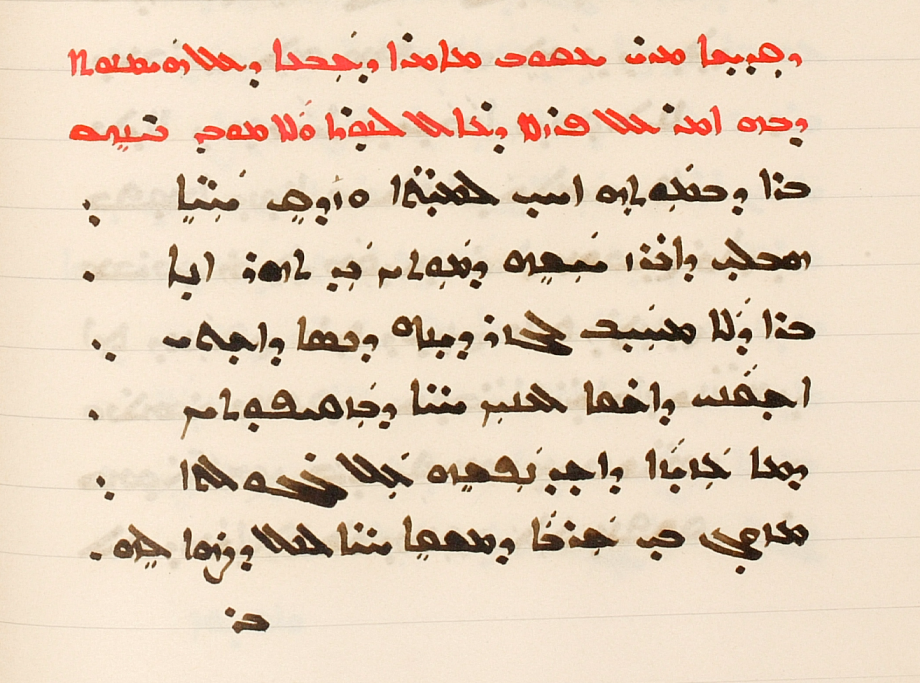

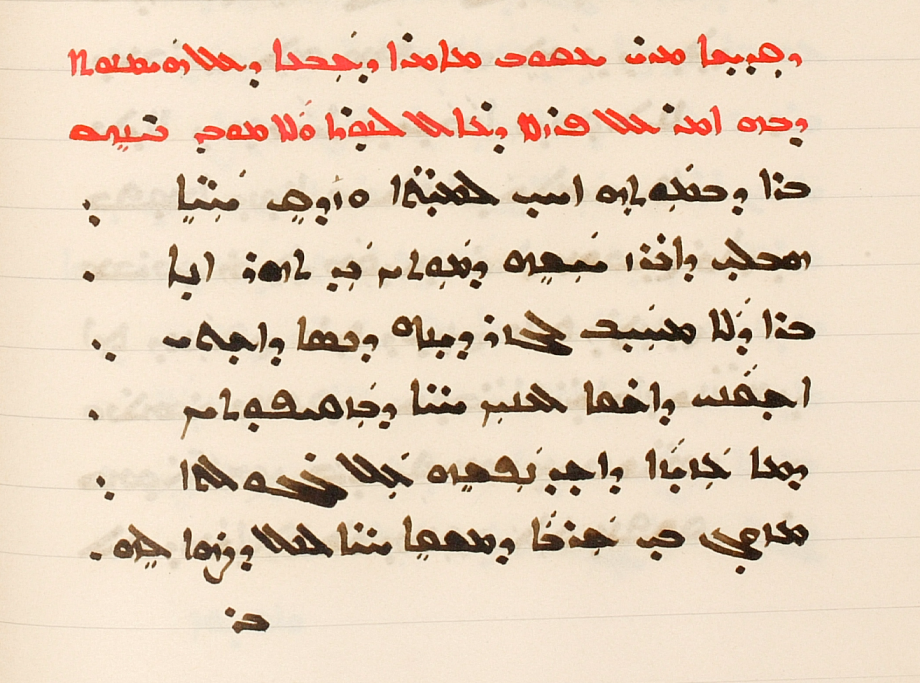

CFMM 167, p. 22

pp. 1-22 Memra on the Faith, 6

- Syriac title ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܫܬܐ ܕܥܠ ܗܝܡܢܘܬܐ

- Incipit ܐܚ̈ܝ ܢܥܪܘܩ ܡܢ ܟܣܝ̈ܬܐ ܕܠܐ ܡܬܒܨ̈ܝܢ

pp. 22-56, Memra on the Faith, 7, in which he Talks about the Iron that Enters the Fire and does not Lose its Nature

- Syriac title ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܫܒܥܐ ܕܥܠ ܗܝܡܢܘܬܐ ܕܒܗ ܐܡܪ ܥܠ ܦܪܙܠܐ ܕܥܐܠ ܠܢܘܪܐ ܘܠܐ ܡܘܒܕ ܟܝܢܗ

- Incipit ܒܪܐ ܕܒܡܘܬܗ ܐܚܝ ܠܡܝ̈ܬܐ ܘܙܕܩ ܚܝ̈ܐ

pp. 56-72, Memra on the Faith, in which He Teaches that the Way of Christ Cannot be Investigated

- Syriac title ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܗܝܡܢܘܬܐ ܕܒܗ ܡܘܕܥ ܥܠ ܐܘܪܚܗ ܕܡܫܝܚܐ ܕܠܐ ܡܬܒܨܝܐ

- Incipit ܐܝܟ ܕܠܫܘܒܚܟ ܐܙܝܥ ܒܝ ܡܪܝ ܩܠܐ ܪܡܐ

pp. 72-68bis, Memra on the Faith, 10

- Syriac title ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܣܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܗܝܡܢܘܬܐ

- Incipit ܢܫܠܘܢ ܣܦܪ̈ܐ ܡܢ ܥܘܩܒܗ ܕܒܪ ܐܠܗܐ

As a special treat, here is the cover of this manuscript, with a 19th-cent. image of the Golden Horn (Turkish Haliç) and the Unkapanı Bridge (see now Atatürk Bridge):

Front cover of CFMM 167

The Turkish beneath the French is roughly Haliç Dersaadet manzarından Unkapanı köprüsü. Dersaadet is one of the old names of Istanbul.

One of the pleasures of cataloging manuscripts is learning about authors and texts that are relatively little known. One such Syriac author is Athanasios (Abū Ġalib) of Ǧayḥān (Ceyhan). Two fifteenth-century manuscripts, CFMM 417 and 418, which I have recently cataloged, each contain different texts attributed to him. Barsoum surveys his life and work briefly in Scattered Pearls (pp. 441-442), and prior to that Vosté wrote an article on him; more recently Vööbus and Carmen Fotescu Tauwinkl have further reported on him. (See the bibliography below; I have not seen all of these resources.) According to Barsoum, he died in 1177 at over 80 years old. As far as I know, none of his work has been published.

The place name associated with this author is the Turkish Ceyhan. The Syriac spelling of the place in the Gazetteer has gyḥʾn, but in both of these manuscripts it is gyḥn. The former is probably an imitation of the Arabic-script spelling, while the form without ālap in the manuscripts still indicates ā in the second syllable by means of an assumed zqāpā.

Now for the CFMM texts.

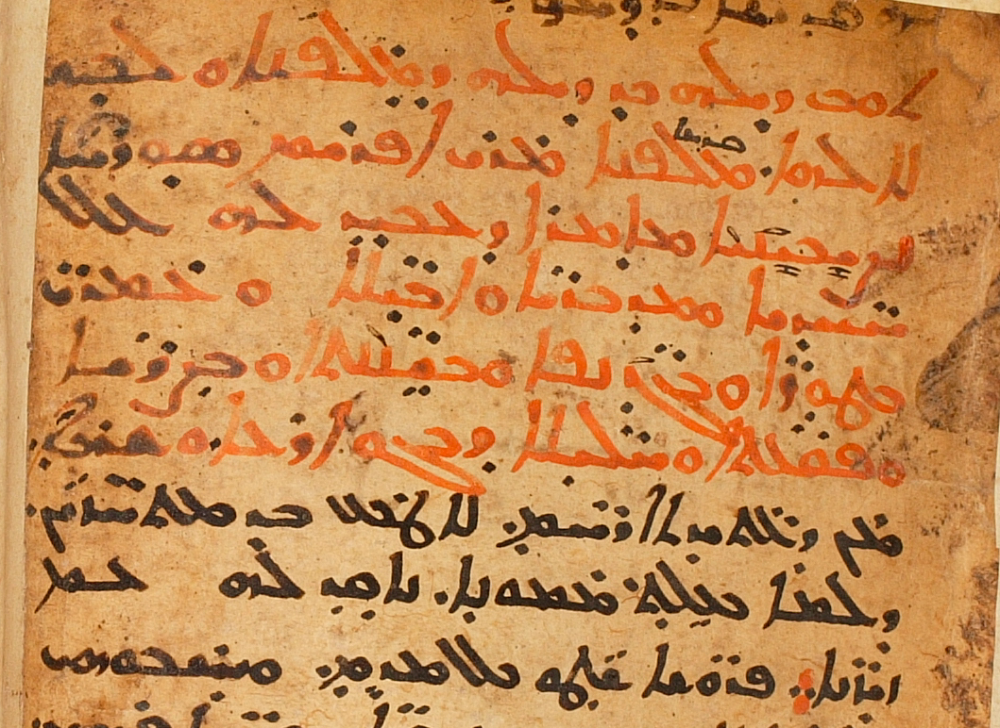

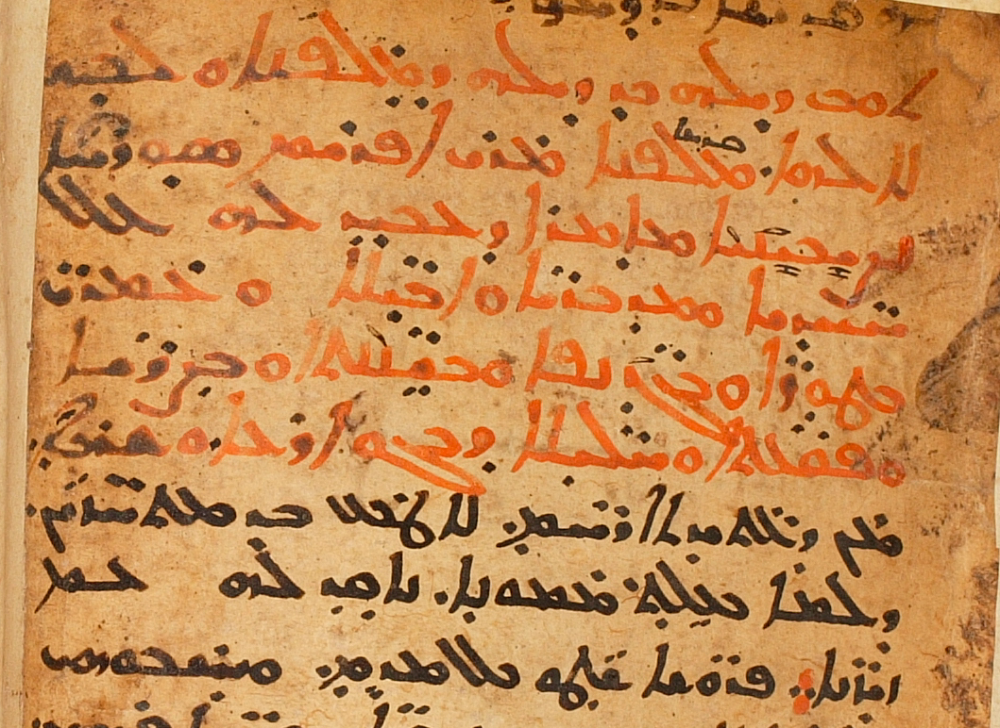

CFMM 417, pp. 465-466

An untitled monastic selection. These two pages make up the whole of this short text. As you can see, it follows something from Isaac of Nineveh, and it precedes Ps.-Evagrius, On the Perfect and the Just (CPG 2465 = Hom. 14 of the Liber Graduum). The manuscript is dated March, 1785 AG (= 1474 CE).

CFMM, p. 465

CFMM 417, p. 466

****

CFMM 418, ff. 235v-243v

Excerpts “from his teaching”. Here are the first and last pages of the text. This longer text follows Isaac of Nineveh’s Letter on how Satan Takes Pains to Remove the Diligent from Silence (ff. 223v-235v, Eggartā ʿal hāy d-aykannā metparras Sāṭānā la-mbaṭṭālu la-ḥpiṭē men šelyā) and precedes some Profitable Sayings attributed to Isaac. This manuscript — written by more than one scribe, but at about the same time, it seems — is dated on f. 277v with the year 1482, but the 14- is to be read 17-, so we have 1782 AG (= 1470/1 CE; cf. Vööbus, Handschriftliche Überlieferung der Mēmrē-Dichtung des Jaʿqōb von Serūg, III 97).

CFMM 418, f. 235v

CFMM 418, f. 243v

Bibliography

Tauwinkl, Carmen Fotescu, “Abū Ghālib, an Unknown West Syrian Spiritual Author of the XIIth Century”, Parole de l’Orient 36 (2010): 277-284.

Tauwinkl, Carmen Fotescu, “A Spiritual Author in 12th Century Upper Mesopotamia: Abū Ghālib and his Treatise on Monastic Life”, Pages 75-93 in The Syriac Renaissance. Edited by Teule, Herman G.B. and Tauwinkl, Carmen Fotescu and ter Haar Romeny, Robert Bas and van Ginkel, Jan. Eastern Christian Studies 9. Leuven / Paris / Walpole, MA: Peeters, 2010.

Vööbus, Arthur, History of Asceticism in the Syrian Orient: A Contribution to the History of Culture in the Near East, III, CSCO 500, Subs. 81. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1988, pp. 407-410.

Vööbus, Arthur, “Important Discoveries for the History of Syrian Mysticism: New Manuscript Sources for Athanasius Abû Ghalîb”, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 35:4 (1976): 269-270.

Vosté, Jacques Marie, “Athanasios Aboughaleb, évêque de Gihân en Cilicie, écrivain ascétique du XIIe siècle”, Revue de l’Orient chrétien III, 6 [26] (1927-1928): 432-438. Available here.

DCA (Chaldean Diocese of Alqosh) 62 contains various liturgical texts in Syriac. It is a fine copy, but the most interesting thing about the book is its colophon. Here first are the images of the colophon, after which I will give an English translation.

DCA 62, f. 110r

DCA 62, f. 110v

English translation (students may see below for some lexical notes):

[f. 110r]

This liturgical book for the Eucharist, Baptism, and all the other rites and blessings according to the Holy Roman Church was finished in the blessed month of Adar, on the 17th, the sixth Friday of the Dominical Fast, which is called the Friday of Lazarus, in the year 2150 AG, 1839 AD. Praise to the Father, the cause that put things into motion and first incited the beginning; thanks to the Son, the Word that has empowered and assisted in the middle; and worship to the Holy Spirit, who managed, directed, tended, helped, and through the management of his care brought [it] to the end. Amen.

[f. 110v]

I — the weak and helpless priest, Michael Romanus, a monk: Chaldean, Christian, from Alqosh, the son of the late deacon Michael, son of the priest Ḥadbšabbā — wrote this book, and I wrote it as for my ignorance and stupidity, that I might read in it to complete my service and fulfill my rank. Also know this, dear reader: that from the beginning until halfway through the tenth quire of the book, it was written in the city of Siirt, and from there until the end of the book I finished in Šarul, which is in the region of the city of Erevan, which is under the control of the Greeks (?), when I was a foreigner, sojourner, and stranger in the village of Syāqud.

The fact that the scribe started his work in Siirt (now in Turkey), relocated, then completed his work, is of interest in and of itself. As for the toponyms, Šarul here must be Sharur/Şərur, now of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (an exclave of Azerbaijan), which at the time of the scribe’s writing was under Imperial Russian control, part of the Armenian Province (Армянская область), and prior to that, part of the Safavid Nakhchivan Khanate, which, with the Erevan Khanate, Persia ceded to Russia at the end of the Russo-Persian War in 1828 with the Treaty of Turkmenchay (Туркманчайский договор, Persian ʿahd-nāme-yi Turkamānčāy). The spelling of Erevan in Syriac above matches exactly the spelling in Persian (ايروان). When the scribe says that Šarul/Sharur/Şərur is in the region of Erevan, he apparently means the Armenian Province, which contained the old Erevan Khanate. He says that the region “is under the control of the Greeks” (yawnāyē); this seems puzzling: the Russians should be named, but perhaps this is paralleled elsewhere. For Syāqud, cf. Siyagut in the Syriac Gazetteer.

See the Erevan and Nakhchivan khanates here called respectively Х(анст)во Ереванское and Х(анст)во Нахичеванское, bordering each other, both in green at the bottom of the map near the center.

For Syriac students, here are some notes, mostly lexical, for the text above:

- šql G sākā w-šumlāyā to be finished (hendiadys)

- ʿyādā custom

- ʿrubtā eve (of the Sabbath) > Friday

- zwʿ C to set in motion

- ḥpṭ D incite (with the preposition lwāt for the object)

- šurāyā beginning

- tawdi thanks (NB absolute)

- ḥyl D to strengthen, empower

- ʿdr D to help, support

- mṣaʿtā middle

- prns Q to manage, rule (cf. purnāsā below)

- dbr D to lead, guide

- swsy Q to heal, tend, foster

- swʿ D to help, assist, support

- ḥartā end

- mnʿ D to reach; to bring

- purnāsā management, guardianship, support (here constr.)

- bṭilutā care, forethought

So we have an outline of trinitarian direction in completing the scribal work: abā — šurāyā; brā — mṣaʿtā; ruḥ qudšā — ḥartā.

- mḥilā weak

- tāḥobā feeble, wretched

- mnāḥ (pass. ptcp of nwḥ C) at rest, contented

- niḥ napšā at rest in terms of the soul > deceased (the first word is a pass. ptcp of nwḥ G)

- mšammšānā deacon

- burutā stupidity, inexperience

- hedyoṭutā stupidity, simplicity (explicitly vocalized hēdyuṭut(y) above)

- šumlāyā fulfilling

- mulāyā completion

- dargā office, rank

- qāroyā reader

- pelgā half, part

- kurrāsā quire

- šlm D to complete, finish

- nukrāyā foreigner

- tawtābā sojourner

- aksnāyā stranger

- qritā village

While cataloging the 15th-century manuscript CFMM 152 (on which see also here), I was struck by the long rubric of this mēmrā attributed to Ephrem.

CFMM 152, p. 156

(Students of Syriac may note the construct state before a preposition in ʿāmray b-ṭurē [Nöldeke, Gramm., § 206], as well as in the common epithet lbiš l-alāhā [Brockelmann, Lexicon Syriacum, 2d ed., 358a].)

Here with English glosses are the nouns in this rubric where monks may dwell. They can all be rocky areas, and there might be some semantic ambiguity and overlap with some of them.

- ṭurā mountain

- gdānpā ledge, crag

- šnāntā rock, crag, peak

- ṣeryā crack, fissure

- pqaʿtā crack (also valley)

- ḥlēlā crack

Brock’s list of incipits tells us that this mēmrā, possibly a genuine work of Ephrem, has been published by Beck in Sermones IV (CSCO 334-335 / Scr. Syr. 148-149, 1973), pp. 16-28. (Published earlier by Zingerle and Rahmani; there are two English translations, neither available to me at the moment.) The rubric in Beck’s ed. differs slightly from the one in this manuscript.

For comparison, here is another mēmrā attributed to Ephrem from a later manuscript, CFMM 157, p. 104. (see Beck, Sermones IV, pp. 1-16, for a published edition of the mēmrā).

CFMM 157, p. 104

This one has some of the same words, but the related addition terms are:

- mʿartā cave (pl. without fem. marker; see Nöldeke, Gramm., § 81)

- šqipā cliff

- pe/aʿrā cave

And so I leave you with these related Syriac terms, in case you wish to write a Syriac poem with events in rocky locales!

Here is a colophon from a manuscript I cataloged last week (CFMM 155, p. 378). It shares common features and vocabulary with other Syriac colophons, but the direct address to the reader, not merely to ask for prayer, but also to suggest that the reader, too, needs rescuing is less common. We often find something like “Whoever prays for the scribe’s forgiveness will also be forgiven,” but the phrasing we find in this colophon is not as common.

CFMM 155, p. 378

Brother, reader! I ask you in the love of Jesus to say, “God, save from the wiles of the rebellious slanderer the weak and frail one who has written, and forgive his sins in your compassion.” Perhaps you, too, should be saved from the snares of the deceitful one and be made worthy of the rank of perfection. Through the prayers of Mary the Godbearer and all the saints! Yes and yes, amen, amen.

Here are a few notes and vocabulary words for students:

- pāgoʿā reader (see the note on the root pgʿ in this post)

- ḥubbā Išoʿ should presumably be ḥubbā d-Išoʿ

- pṣy D to save; first paṣṣay(hy) D impv 2ms + 3ms, then tetpaṣṣē Dt impf 2ms

- mḥil weak

- tāḥub weak

- ākel-qarṣā crumb-eater, i.e. slanderer, from an old Aramaic (< Akkadian) idiom ekal qarṣē “to eat the crumbs (of)” > “to slander” (see S.A. Kaufman, Akkadian Influences on Aramaic, p. 63) (cf. διάβολος < διαβάλλω)

- ṣenʿtā plot (for ṣenʿātēh d-ākel-qarṣā cf. Eph 6:11 τὰς μεθοδείας τοῦ διαβόλου)

- mārod rebellious

- paḥḥā trap, snare

- nkil deceitful

- šwy Gt to be equal, to be made worthy, deserve

- dargā level, rank

- gmirutā perfection

I learned earlier this week from a tweet by Matthew Crawford (@mattrcrawford) that the Rabbula Gospels are freely available to view online in fairly high-quality images. This sixth-century manuscript (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 1.56) is famous especially for its artwork at the beginning of the codex before, surrounding, and following the Eusebian canon tables, including both figures from biblical history and animals: prophets, Mary, Jesus, scenes from the Gospels (Judas is hanging from a tree on f. 12r), the evangelists, birds, deer, rabbits, &c. Beginning on f. 13r, the folios are strictly pictures, the canon tables having been completed. These paintings are very pleasing, but lovers of Syriac script have plenty to feast on, too. The main text itself is written in large Estrangela, with the colophon (f. 291v-292v) also in Estrangela but mostly of a much smaller size. Small notes about particular lections are often in small Serto. The manuscript also has several notes in Syriac, Arabic, and Garšūnī in various hands (see articles by Borbone and Mengozzi in the bibliography below). From f. 15v to f. 19r is an index lectionum in East Syriac script. The Gospel text itself begins on f. 20r with Mt 1:23 (that is, the very beginning of the Gospel is missing).

The images are found here. (The viewer is identical to the one that archive.org uses.)

Rabbula Gospels, f. 231r, from the story of Jesus’ turning the water into wine, Jn 2.

Rabbula Gospels, f. 5r. The servants filling the jugs with the water that will become wine.

For those interested in studying this important manuscript beyond examining these now accessible images, here are a few resources:

Bernabò, Massimò, ed. Il Tetravangelo di Rabbula: Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 1.56. L’illustrazione del Nuovo Testamento nella Siria del VI secolo. Folia picta 1. Rome, 2008. A review here.

Bernabò, Massimò, “Miniature e decorazione,” pp. 79-112 in Il Tetravangelo di Rabbula.

Bernabò, Massimò, “The Miniatures in the Rabbula Gospels: Postscripta to a Recent Book,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 68 (2014): 343-358. Available here.

Borbone, Pier Giorgio, “Codicologia, paleografia, aspetti storici,” pp. 23-58 in Il Tetravangelo di Rabbula. Available here.

Borbone, Pier Giorgio, “Il Codice di Rabbula e i suoi compagni. Su alcuni manoscritti siriaci della Biblioteca medicea laurenziana (Mss. Pluteo 1.12; Pluteo 1.40; Pluteo 1.58),” Egitto e Vicino Oriente 32 (2009): 245-253. Available here.

Borbone, Pier Giorgio, “L’itinéraire du “Codex de Rabbula” selon ses notes marginales,” pp. 169-180 in F. Briquel-Chatonnet and M. Debié, eds., Sur les pas des Araméens chrétiens. Mélanges offerts à Alain Desreumaux. Paris, 2010. Available here.

Botte, Bernard, “Note sur l’Évangéliaire de Rabbula,” Revue des sciences religieuses 36 (1962): 13-26.

Cecchelli, Carlo, Giuseppe Furlani, and Mario Salmi, eds. The Rabbula Gospels: Facsimile Edition of the Miniatures of the Syriac Manuscript Plut. I, 56 in the Medicaean-Laurentian Library. Monumenta occidentis 1. Olten and Lausanne, 1959.

Leroy, Jules, “L’auteur des miniatures du manuscrit syriaque de Florence, Plut. I, 56, Codex Rabulensis,” Comptes-rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Paris 98 (1954): 278-283.

Leroy, Jules, Les manuscrits syriaques à peintures, conservés dans les bibliothèques d’Europe et d’Orient. Contribution à l’étude de l’iconographie des églises de langue syriaque. Paris, 1964.

Macchiarella, Gianclaudio, “Ricerche sulla miniatura siriaca del VI sec. 1. Il codice. c.d. di Rabula,” Commentari NS 22 (1971): 107-123.

Mango, Marlia Mundell, “Where Was Beth Zagba?,” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 7 (1983): 405-430.

Mango, Marlia Mundell, “The Rabbula Gospels and Other Manuscripts Produced in the Late Antique Levant,” pp. 113-126 in Il Tetravangelo di Rabbula.

Mengozzi, Alessandro, “Le annotazioni in lingua araba sul codice di Rabbula,” pp. 59-66 in Il Tetravangelo di Rabbula.

Mengozzi, Alessandro, “The History of Garshuni as a Writing System: Evidence from the Rabbula Codex,” pp. 297-304 in F. M. Fales & G. F. Grassi, eds., CAMSEMUD 2007. Proceedings of the 13th Italian Meeting of Afro-Asiatic Linguistics, held in Udine, May 21st-24th, 2007. Padua, 2010.Available here.

Paykova, Aza Vladimirovna, “Четвероевангелие Раввулы (VI в.) как источник по истории раннехристианского искусства,” (The Rabbula Gospels (6th cent.) as a Source for the History of Early Christian Art) Палестинский сборник 29 [92] (1987): 118-127.

Rouwhorst, Gerard A.M., “The Liturgical Background of the Crucifixion and Resurrection Scene of the Syriac Gospel Codex of Rabbula: An Example of the Relatedness between Liturgy and Iconography,” pp. 225-238 in Steven Hawkes-Teeples, Bert Groen, and Stefanos Alexopoulos, eds., Studies on the Liturgies of the Christian East: Selected Papers of the Third International Congress of the Society of Oriental Liturgy Volos, May 26-30, 2010. Eastern Christian Studies 18. Leuven / Paris / Walpole, MA, 2013.

Sörries, Reiner, Christlich-antike Buchmalerei im Überblick. Wiesbaden, 1993.

van Rompay, Lucas, “‘Une faucille volante’: la représentation du prophète Zacharie dans le codex de Rabbula et la tradition syriaque,” pp. 343-354 in Kristoffel Demoen and Jeannine Vereecken, eds., La spiritualité de l’univers byzantin dans le verbe et l’image. Hommages offerts à Edmond Voordeckers à l’occasion de son éméritat. Instrumenta Patristica 30. Steenbrugis and Turnhout, 1997.

Wright, David H., “The Date and Arrangement of the Illustrations in the Rabbula Gospels,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 27 (1973): 199-208.

I have returned to the CFMM collection for some more cataloging work, and I am now continuing with a series of Syriac homiletic manuscripts, including especially the work of Jacob of Serug. Far into one of these manuscripts (CFMM 134), the following note in Arabic appears:

CFMM 134, p. 666

Here is an ET with a few comments:

Let the reader understand, be informed, and advise [those] near him and everyone that they should give glory to the Son of God, who receives the repentant, who saves his church from drowning in sins and from eternal damnation.

- Let the reader understand cf. Mk 13:14, ὁ ἀναγινώσκων νοεῖτω.

- al-muḫalliṣ might better be read without the article, in construct with kanīsatihi, but here the latter word is vocalized kanīsatahu (ACC, not GEN), and so the writer clearly had a verbal (“saving, one who saves [X]”), rather than nominal (“savior [of X]”), function in view for the participle al-muḫalliṣ.

- ġarīq here seems to = ġaraq.

- drowning in sins (or the like) is a common expression; another example is in this post.

I have written before on the page from CCM 10 that has the Trisagion in various languages, all in Syriac script. Let’s take a look specifically at the Turkish part now:

CCM 10, f. 8r, trisagion in Turkish written with Syriac letters

The readings of this one are more obvious than the Georgian part we looked at before. Here is a possible transcription:

arı Taŋrı, arı güçlü, arı ölmez

rahmet bizüm ʾwsnʾ eyle!

Notes

arı pure, clean (a homonym means bee, wasp). For “holy” in Isa 6:3, Ali Bey has kuddûs, and the same seems to be the norm in related places (e.g. Rev 4:8), too, in Ali Bey’s version and later translations. (For Ottoman translations of the Bible, see here.)

Taŋrı God (< sky). Here spelled tgry. The ŋ in this word (mod. Tanrı) was written in Ottoman with the ڭ (where so marked) or with نڭ. For the earlier history of the word see G. Clauson, An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Thirteenth-Century Turkish, pp. 523-524; Turkish and Mongolian Studies, pp. 9-10, 220, 223. It appears in other Turkic languages, too, such as Tatar тәңре. From a Turkic language the word came into Mongolian (sky, heaven, deity; in addition to the above references, cf. N. Poppe, Introduction to Mongolian Comparative Studies, p. 45). The word is listed, of course, in Kāšġarī’s famous work on Turkic languages; see vol. 3: 278-279 of edition available here (PDF); no other edition is available to me now, but for a Russian translation, see № 6418 in the Z.-A. Auezova’s 2005 work (Мах̣мӯд ал-Ка̄шг̣арӣ, Дӣва̄н Луг̣а̄т ат-Турк). (Clauson and others — such as K. Shiratori, Über die Sprache des Hiung-nu Stammes und der Tung-hu Stämme, pp. 3-4 — point to an early occurrence of the word in Chinese garb in the 漢書 Hàn Shū: the form is 撐犁, modern chēng lí < t’ʿäng liei < tʿäng liǝr. The passage is in the last part of the Hàn Shū, the biographies, chapter (94) 匈奴傳上, § 10, available here.) Whether or not there is a real connection, the Turkic word does immediately bring to mind Sumerian diĝir (which we might just as well spell diŋir).

güçlü strong, powerful, mighty. Note in the Syriac script that ç is indicated by a gāmal with an Arabic ǧīm beneath it.

ölmez immortal, undying (the root of ölmek to die + neg. suffix -mAz)

bizüm 1pl pron gen. We might expect the dative bize, but the phrase here (lit. do our mercy) is not altogether unclear; but see the note to the following word. Analogous phrases in Ottoman versions of the Bible do have the dative:

- Ps 123:3 Ali Bey ʿināyet eyle bize

- Ps 123:3 Turabi Effendi merhamet eyle bize

- Lk 18:38 Ali Bey (with 1sg) baŋa merhamet eyle

ʾwsnʾ I’m not immediately sure how to take this word. Possibly a mistake for üstüne upon, a postposition with bizüm for object?

eyle impv of the auxiliary verb eylemek to do, make, here with rahmet: to have mercy, be merciful

To file in “unexpected finds”: With no apparent relationship to the rest of the text on the page, the Georgian mxedruli alphabet (along with Armenian) is found in the large outer margin of a Syriac manuscript from Jerusalem containing the Lexicon attributed to Eudochus, &c. (SMMJ 295, perh. 19th cent.).

SMMJ 295, p. 277

Here “Georgian” in Syriac is gergānāytā. The writing begins with ქ, presumably for ქრისტე “Christ!”, and ends with ამ(ე)ნ “Amen”. The handwriting is not bad at all. There is no ჳ between the ტ and უ, but the other four letters obsolete in later Georgian (ჱ, ჲ, ჴ, ჵ) are here.

As anyone who frequents this blog knows, manuscripts can be much more than simple receptacles for the main texts that their scribes copied. When present, colophons, notes, &c., may make a manuscript even more valuable and interesting. Here is a case in point. On f. 241r of SMMJ 211, a fifteenth-century copy of Bar ʿEbrāyā’s Chronography (secular & eccles.), are two later meteorological reports from different hands, neither the scribe’s.

Notes in outer column of SMMJ 211, f. 241r.

The first note says roughly in English:

In the year 1814 (= 1502/3 CE) AG, in the month of Ḥzirān, there was a white meteor like the darkest night in the middle of the air for about an hour in the day, and everyone [lit. the whole world] saw it. And in the same year, on the feast of St. Jacob, on the 29th of the month of Tammuz, there was great and powerful thunder before midday, and with it were white clouds (ʿnānā), yet without a mist (ʿaymā) in the air, or rain, and this thunder continued roaring for about an hour of the day. They heard its sound throughout the region all the way to Gāzartā and the valley, and many people were frightened of its sound and fell on their faces. While the Lord shows us these signs for us to be repentant, our insolent and refractory heart neither repents nor is softened. May the Lord not repay us according to our evils, but according to the multitude of his mercy — amen — and his grace.

And from almost seven decades later, the second note (in less careful handwriting) says:

In the year 1882 AG (= 1570/1 CE) the clouds thickened and much rain appeared in Ṭur ʿĀbdin with terrible thunder, and intense lightning came down for six days in the month of Āb during the Feast of Booths in the villages, one of which is called Zāz, before the outer land of the Church of Mar Dimeṭ, and this lightning came down upon a house near that church with wood and straw inside it, and the house caught fire [with] all the firewood and straw.

(For the Church of Mar Dimet in Zaz, see a picture here.)

Update: Thanks to Thomas Carlson for the suggestion about PQʿTʾ (valley) in the first note, which I initially read as an unidentified place-name PWʿTʾ. The scribe writes waw and qop with little difference.