Archive for the ‘scribes’ Tag

DCA (Chaldean Diocese of Alqosh) 62 contains various liturgical texts in Syriac. It is a fine copy, but the most interesting thing about the book is its colophon. Here first are the images of the colophon, after which I will give an English translation.

DCA 62, f. 110r

DCA 62, f. 110v

English translation (students may see below for some lexical notes):

[f. 110r]

This liturgical book for the Eucharist, Baptism, and all the other rites and blessings according to the Holy Roman Church was finished in the blessed month of Adar, on the 17th, the sixth Friday of the Dominical Fast, which is called the Friday of Lazarus, in the year 2150 AG, 1839 AD. Praise to the Father, the cause that put things into motion and first incited the beginning; thanks to the Son, the Word that has empowered and assisted in the middle; and worship to the Holy Spirit, who managed, directed, tended, helped, and through the management of his care brought [it] to the end. Amen.

[f. 110v]

I — the weak and helpless priest, Michael Romanus, a monk: Chaldean, Christian, from Alqosh, the son of the late deacon Michael, son of the priest Ḥadbšabbā — wrote this book, and I wrote it as for my ignorance and stupidity, that I might read in it to complete my service and fulfill my rank. Also know this, dear reader: that from the beginning until halfway through the tenth quire of the book, it was written in the city of Siirt, and from there until the end of the book I finished in Šarul, which is in the region of the city of Erevan, which is under the control of the Greeks (?), when I was a foreigner, sojourner, and stranger in the village of Syāqud.

The fact that the scribe started his work in Siirt (now in Turkey), relocated, then completed his work, is of interest in and of itself. As for the toponyms, Šarul here must be Sharur/Şərur, now of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (an exclave of Azerbaijan), which at the time of the scribe’s writing was under Imperial Russian control, part of the Armenian Province (Армянская область), and prior to that, part of the Safavid Nakhchivan Khanate, which, with the Erevan Khanate, Persia ceded to Russia at the end of the Russo-Persian War in 1828 with the Treaty of Turkmenchay (Туркманчайский договор, Persian ʿahd-nāme-yi Turkamānčāy). The spelling of Erevan in Syriac above matches exactly the spelling in Persian (ايروان). When the scribe says that Šarul/Sharur/Şərur is in the region of Erevan, he apparently means the Armenian Province, which contained the old Erevan Khanate. He says that the region “is under the control of the Greeks” (yawnāyē); this seems puzzling: the Russians should be named, but perhaps this is paralleled elsewhere. For Syāqud, cf. Siyagut in the Syriac Gazetteer.

See the Erevan and Nakhchivan khanates here called respectively Х(анст)во Ереванское and Х(анст)во Нахичеванское, bordering each other, both in green at the bottom of the map near the center.

For Syriac students, here are some notes, mostly lexical, for the text above:

- šql G sākā w-šumlāyā to be finished (hendiadys)

- ʿyādā custom

- ʿrubtā eve (of the Sabbath) > Friday

- zwʿ C to set in motion

- ḥpṭ D incite (with the preposition lwāt for the object)

- šurāyā beginning

- tawdi thanks (NB absolute)

- ḥyl D to strengthen, empower

- ʿdr D to help, support

- mṣaʿtā middle

- prns Q to manage, rule (cf. purnāsā below)

- dbr D to lead, guide

- swsy Q to heal, tend, foster

- swʿ D to help, assist, support

- ḥartā end

- mnʿ D to reach; to bring

- purnāsā management, guardianship, support (here constr.)

- bṭilutā care, forethought

So we have an outline of trinitarian direction in completing the scribal work: abā — šurāyā; brā — mṣaʿtā; ruḥ qudšā — ḥartā.

- mḥilā weak

- tāḥobā feeble, wretched

- mnāḥ (pass. ptcp of nwḥ C) at rest, contented

- niḥ napšā at rest in terms of the soul > deceased (the first word is a pass. ptcp of nwḥ G)

- mšammšānā deacon

- burutā stupidity, inexperience

- hedyoṭutā stupidity, simplicity (explicitly vocalized hēdyuṭut(y) above)

- šumlāyā fulfilling

- mulāyā completion

- dargā office, rank

- qāroyā reader

- pelgā half, part

- kurrāsā quire

- šlm D to complete, finish

- nukrāyā foreigner

- tawtābā sojourner

- aksnāyā stranger

- qritā village

Here is a colophon from a manuscript I cataloged last week (CFMM 155, p. 378). It shares common features and vocabulary with other Syriac colophons, but the direct address to the reader, not merely to ask for prayer, but also to suggest that the reader, too, needs rescuing is less common. We often find something like “Whoever prays for the scribe’s forgiveness will also be forgiven,” but the phrasing we find in this colophon is not as common.

CFMM 155, p. 378

Brother, reader! I ask you in the love of Jesus to say, “God, save from the wiles of the rebellious slanderer the weak and frail one who has written, and forgive his sins in your compassion.” Perhaps you, too, should be saved from the snares of the deceitful one and be made worthy of the rank of perfection. Through the prayers of Mary the Godbearer and all the saints! Yes and yes, amen, amen.

Here are a few notes and vocabulary words for students:

- pāgoʿā reader (see the note on the root pgʿ in this post)

- ḥubbā Išoʿ should presumably be ḥubbā d-Išoʿ

- pṣy D to save; first paṣṣay(hy) D impv 2ms + 3ms, then tetpaṣṣē Dt impf 2ms

- mḥil weak

- tāḥub weak

- ākel-qarṣā crumb-eater, i.e. slanderer, from an old Aramaic (< Akkadian) idiom ekal qarṣē “to eat the crumbs (of)” > “to slander” (see S.A. Kaufman, Akkadian Influences on Aramaic, p. 63) (cf. διάβολος < διαβάλλω)

- ṣenʿtā plot (for ṣenʿātēh d-ākel-qarṣā cf. Eph 6:11 τὰς μεθοδείας τοῦ διαβόλου)

- mārod rebellious

- paḥḥā trap, snare

- nkil deceitful

- šwy Gt to be equal, to be made worthy, deserve

- dargā level, rank

- gmirutā perfection

Here is a simple scribal note on a page of manuscript 152 of the Church of the Forty Martyrs, Mardin (CFMM), a book dated 1780 AG (= 1468/9 CE) and containing mēmrē attributed to Isaac, Ephrem, and Jacob. On p. 59, where the date is given, in addition to the name Gabriel, which also occurs in this note, we see the name Abraham as another partner in producing the manuscript, which was copied at the Monastery of Samuel.

CFMM 152, p. 145

Here’s the Syriac and an English translation, followed by a few notes for students.

d-pāgaʿ w-qārē nšammar ṣlotā l-Gabriʾēl da-npal b-hālēn ḥaššē wa-ktab hānā ptāḥā a(y)k da-l-ʿuhdānā w-meṭṭul reggat ṣlotā d-ḥussāyā da-ḥṭāhē

Whoever comes upon and reads [this note], let him send a prayer for Gabriel, who has fallen into these sufferings and has written this page-spread as a memorial and due to a longing for a prayer for the forgiveness of [his] sins.

A few notes on the passage:

- The verb pgaʿ, semantically similar to Greek ἐντυγχάνειν, often means “to read” and is commonly paired with qrā in notes and colophons.

- šmr D + ṣlotā means “to direct, send, utter a prayer”.

- ḥaššē may not refer to any specific pains or illness. Scribes are generally all too happy to remind their readers that it was in difficult circumstances — of environment, body, mind, etc. — that they wielded their pens!

- ptāḥā means “the opening” (ptaḥ to open), that is, the two-page spread of an open book.

- The purpose, commonly mentioned in notes and colophons, of Gabriel’s copying this book is to remind readers to pray for his sins.

At the end of one of the texts in SMMJ 183, which contains theological and hagiographic writings in Garšūnī, some later reader (or readers?) — the handwriting does not seem to be the same as the scribe’s — has recorded some intended wisdom. The two four-line sayings are in Arabic, but written in both Syriac and Arabic script.

SMMJ 183, f. 98v

This is not the prettiest handwriting, and the spelling might not be what is expected, but the meaning of both is relatively clear. (For the long vowels at line-end, cf. Wright, Grammar, vol. 2, § 224.) The sideways text in the center has its Arabic-script version is on the bottom.

O seeker of knowledge! Apply yourself to piety,

Forgo sleep and subdue satiety,

Continue studying and don’t leave it,

For knowledge consists and grows in study.

On the right we have four more lines in Garšūnī, with its Arabic-script version immediately below.

O child of Adam! You are ignorant!

There is no more awaiting the reckoning:

Look! Your life and your time have vanished.

Now you shall return to dust.

In line 2, al-ḥisābi (written –ī) must be genitive with the foregoing V maṣdar, tanaẓẓur; the latter word is written with ḍ in the Arabic text, but a derivative of “to blossom” doesn’t make much sense, and the Garšūnī writing of ṭ, even without a dot, is known well for ẓ. In the last word of these lines, the Garšūnī version lacks the preposition l-, but it’s present in the Arabic version and is needed for the sense in any case.

Finally, the three Garšūnī lines on the far left read, “Our trust is in God, the quickener of our souls. To him be glory forever.”

Marginal notes of any kind, whether by the original scribe or by a later owner or reader, are among the unique parts of a particular manuscript, no matter how many other copies of the main text may exist. Here, as a simple example of such notes, and for those that might like some easy practice reading Garšūnī and Arabic, are two images from SMMJ 168, a collection of homilies attributed to Ephrem, Jacob of Serugh, John Chrysostom, and others in Garšūnī. They are both written by a reader and secondary scribe named Isaac (here spelled Īsḥāq). The first one is in Arabic script:

SMMJ 168, f. 240r, margin

iġfirū* li-rabbān Īsḥāq

Forgive Rabbān Īsḥāq!

*Missing the alif otiosum.

The second one, several folios later, is written around the outer and lower margin, all in Syriac script (but Arabic language) except for the last three words, which are in Arabic.

SMMJ 168, f. 270r

hāḏihi ‘l-waǧh katībat al-ʕabd al-ḫāṭiʔ rabbān Īsḥāq bi-sm qass wa-rāhib. taraḥḥam ʕalay-hi wa-ʕalá wāliday-hi ayyuhā ‘l-qānī wa-‘l-qāriʔ. raḥimaka ‘llāhu āmīn.

This side [of the folio] is the writing of the sinful slave Rabbān Īsḥāq, [who is] in name a priest and monk. O owner and reader, plead for mercy for him and his parents! May God be merciful to you! Amen!

My involvement in cataloging Syriac and Arabic manuscripts over the last few years has impressed upon me how often and actively Syriac Orthodox and Chaldean scribes (and presumably, readers) used Garšūnī: it is anything but an isolated occurrence in these collections. This brings to the fore questions of how these scribes and readers thought about Garšūnī. Did they consider it simply a writing system, a certain kind of Arabic, or something else? At least a few specific references to “Garšūnī” in colophons may help us answer them. Scribes sometimes make reference to their transcriptions from Arabic script into Syriac script, and elsewhere a scribe mentions translation “from Garšūnī into Syriac” (CFMM 256, p. 344; after another text in the same manuscript, p. 349, we have in Arabic script “…who transcribed and copied [naqala wa-kataba] from Arabic into Garšūnī”). Such statements show that scribes certainly considered Arabic and Garšūnī distinctly.

While cataloging Saint Mark’s Monastery, Jerusalem, (SMMJ) № 167 recently, I found in the colophon a reference to Garšūnī unlike any that I’d seen before, in which the scribe refers, not to the Garšūnī “text” or “copy” (nusḫa, as in SMMJ 140, f. 132v), but rather to “the Garšūnī language” (lisān al-garšūnī). Here is an English translation of the relevant part of the colophon, with the images from the manuscript below.

SMMJ 167, ff. 322r-322v

…[God], in whose help this blessed book is finished and completed, the book of Mar Ephrem the Syrian. The means for copying it were not available with us at the monastery, so we found it with a Greek [rūmī] priest from Beit Jala, a friend of ours, and we took it on loan, so that we could read in it. We observed that it was a priceless jewel. It was written in Arabic, so we, the wretched, with his holiness, our revered lord, the honored Muṭrān, Ǧirǧis Mār Grigorios, were interested in transcribing it into the Garšūnī language, so that reading it might be easy for the novice monks, that they might obtain the salvation of their souls.

This was in the year 1882 AD, the 11th of the blessed month of June…

SMMJ 167, f. 322r (bottom)

SMMJ 167, f. 322v (top)

This is the second explicit reference I have found where a Garšūnī text is considered more readable to at least some section of the literate population. In this case, the audience in view is a group of beginning monks, and in the aforementioned manuscript SMMJ 140 the transcription from Arabic into Garšūnī was made “to facilitate the understanding of its contents for every reader.”

UPDATE (June 17, 2014): Thanks to Salam Rassi for help on the phrase ʕalá sabīl al-ʕīra.

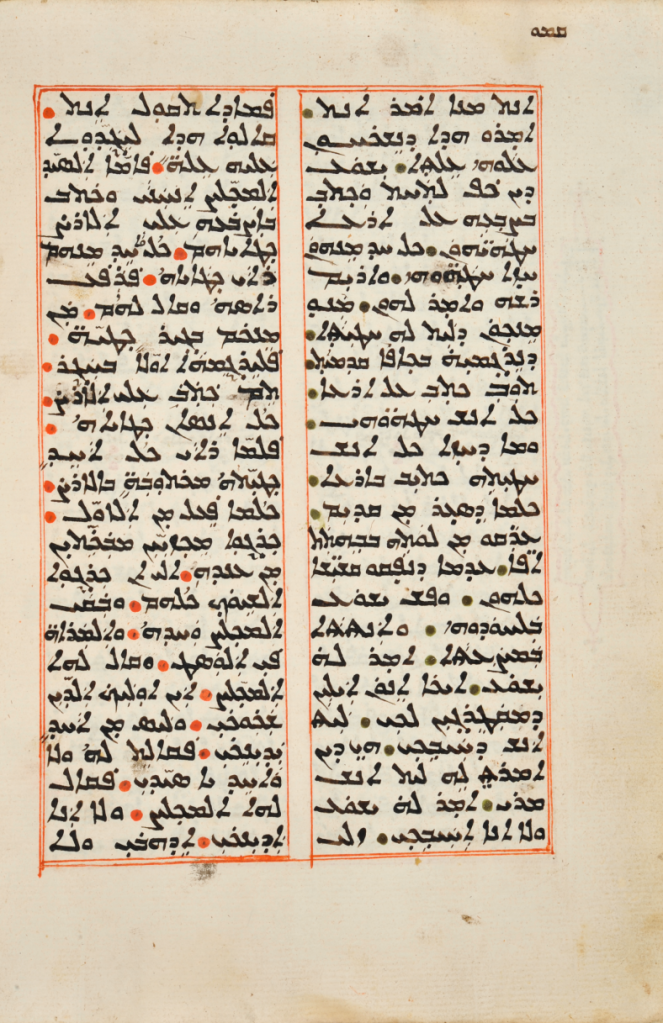

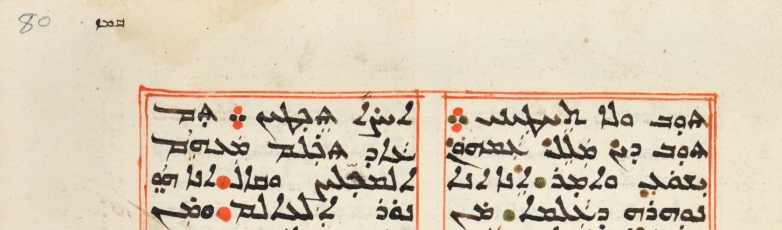

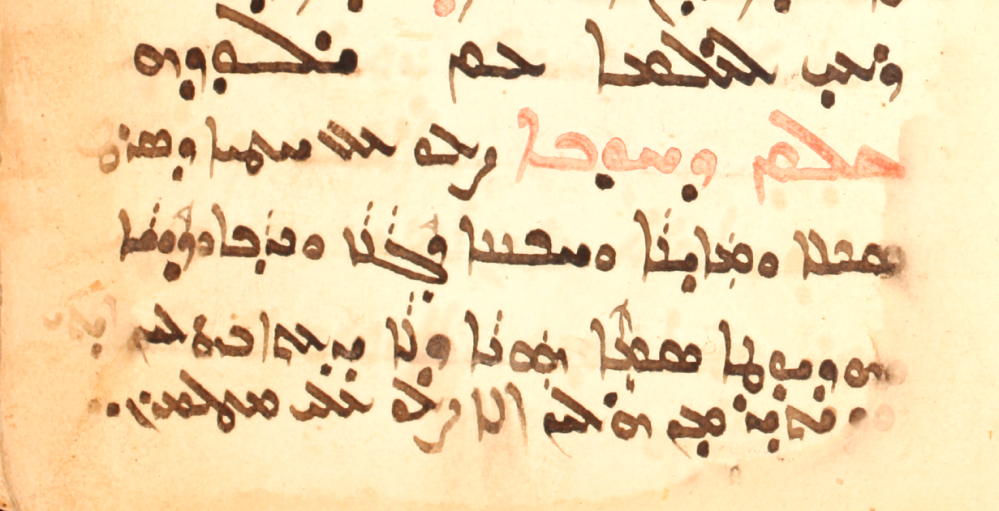

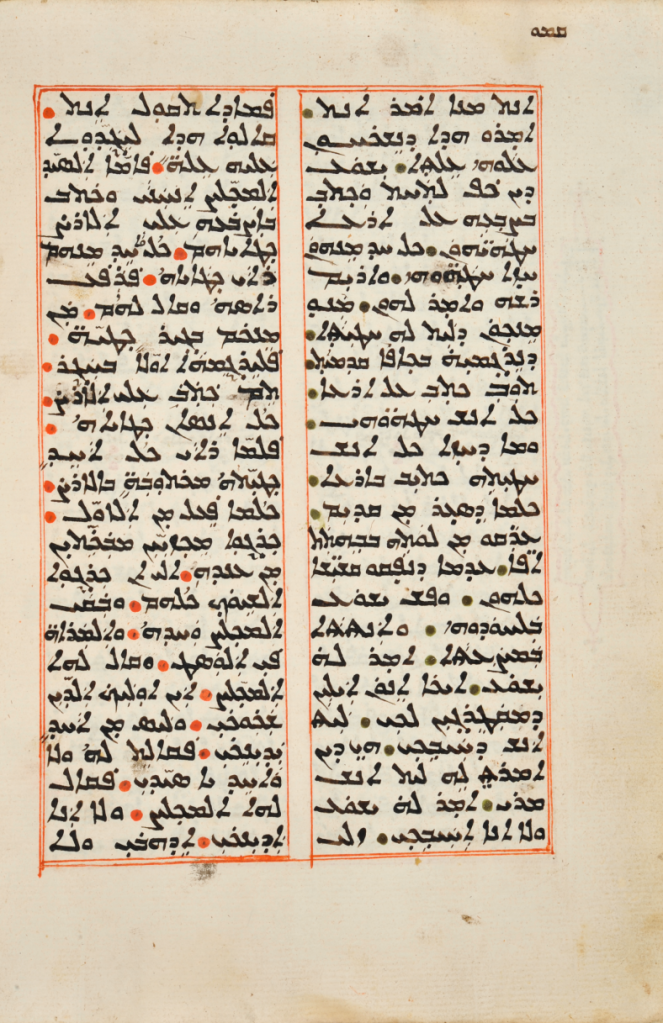

The famous passage known as the pericope adulterae, about which there is a long bibliography and on which Chris Keith has written perhaps most recently (e.g. this survey paper and this book), is not a regular part of the Bible in Syriac. That is, it is not in the typical text of the Peshitta, nor in the Old Syriac, nor even the Harqlean, but we have traces of it, on which see Gwynn, Remnants of the Later Syriac Versions of the Bible (1909), lxxi-lxxii, texts on 41-49, and notes on 140. Gwynn (lxxii) refers to a late Syriac copy, which he does not print, “judging from internal evidence that it was merely a translation from the Latin Vulgate probably connected with the action of the Synod of Diamper,” but he does give some Syriac texts of the passage. The situation with biblical texts in Arabic versions generally being more complicated than Syriac, we can’t say much without further work, but in my recent cataloging work I have come across a copy of the passage in both languages in a late seventeenth-century lectionary (CCM 64) with Syriac and Garšūnī in parallel columns. According to this manuscript’s long colophon on ff. 202r-205r, the book was finished on 7 Ḥzirān (June), a Friday, 1695 AD and 2006 AG, written in the village of ʕayn Tannūr by a scribe named ʕabdā l-ḥad, whose name is given explicitly and also cryptically and acrostically in the series of words ʕabdā bṣirā dawyā allilā lellā ḥbannānā d-šiṭ min kolhon bnaynāšā (“unworthy slave, weak, insignificant, foolish, slothful, more wretched than anyone”).

The text appears in the lection on ff. 77v-80r, for the fifth Sunday of the Fast (Lent), which contains John 7:37-8:20. In a marginal note, the scribe notifies the reader that the verses we call 7:53-8:11 are not in Syriac copies, but he has translated them from Latin:

CCM 64, f. 79r, marginal note

Know, dear reader, that this pericope [pāsoqā] is lacking in our Syriac copy [lit. the copy of us Syriac people], but we have seen it among the Latins [r(h)omāyē], and we have translated it into our Syriac language and into Arabic. Pray for the poor scribe!

John 7:53, in both languages is written interlinearly, but 8:1-8:11 appear just like the rest of the text. (The word pāsoqā above can mean “verse” as well as “section, pericope”; given the history of this passage, in Syriac and other languages, I have taken the word to have the latter meaning here, and not to be merely a reference to the interlinear verse.) Were it not for the marginal note, the reader would have no idea that the passage does not normally occur in the text. Here, then, is a little something for other Syriac and Arabic/Garšūnī readers; I have not compared this Syriac version carefully with those given by Gwynn, but for anyone who wishes to do so, here it is. Happy reading!

CCM 64, f. 79r

CCM 64, f. 79v

CCM 64, f. 80r

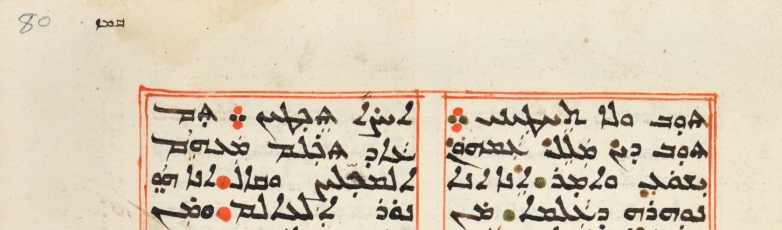

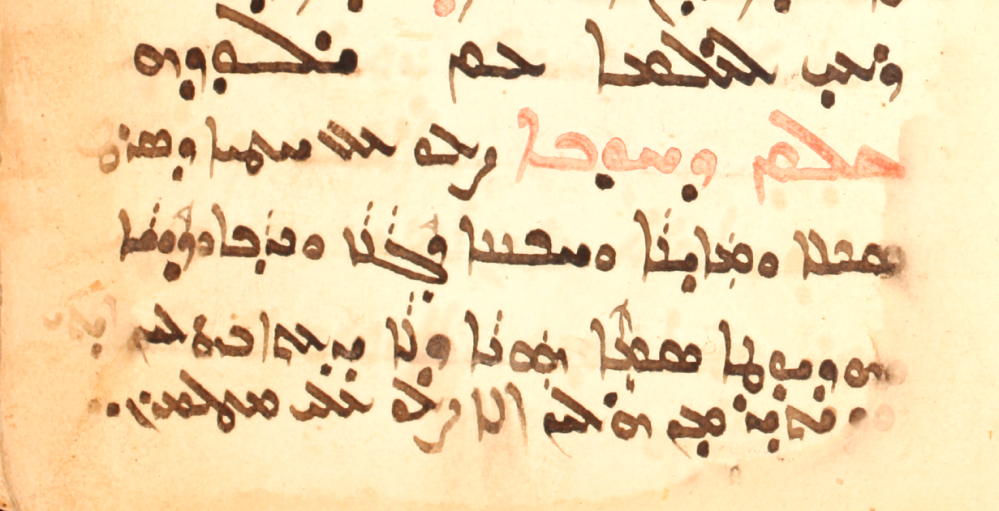

For some brief Friday fun, here’s part of a colophon that shows a little playful cleverness from a scribe. The manuscript CCM 58 (olim Mardin 7), a New Testament manuscript dated July 2053 AG (= 1742 CE) and copied in Alqosh, has a long colophon, including the following few colorful (literally and figuratively) lines near the end, at the bottom of one page and the top of the next:

CCM 58, f. 227v

CCM 58, f. 228r

That is:

Lord, may the payment of the five twins that have toiled, worked, labored, and planted good seed in a white field with a reed from the forest not be refused, but may they be saved from the fire of Gehenna! Yes, and amen!

The “five twins” are the scribe’s ten fingers, the “good seed” is the writing, the “white field” is the paper, and the “reed” is the pen. At least some of this imagery is not unique to this manuscript. In any case we have a memorable way of thinking about a scribe’s labor.

Lately I have been cataloging a group of manuscripts from Saint Mark’s Monastery, Jerusalem, that have homiletic contents, especially the mēmrē of Jacob of Serug, including some that are hitherto unpublished. One of these manuscripts is SMMJ 162, from the late 19th or early 20th century. I don’t mention it here so much for the texts the scribe penned into it, but rather for a little colophon left at the end of Jacob’s Mēmrā on Love (cf. Bedjan, vol. 1, 606-627), f. 181r:

SMMJ 162, f. 181r

Pray for the sinner who has written [it], a fool, lazy, slothful, deceitful, a liar, wretched, stupid, blind of understanding, with no knowledge of these things, [nor] more than these things, but pray for me for our Lord’s sake!

Almost from the beginning of my time cataloging at HMML, I have been collecting excerpts of scribal notes and colophons that I found interesting for some reason or other, one such reason being the extreme self-loathing and self-deprecation that scribes not uncommonly trumpet. The cases in which scribes go on and on with adjectives or substantives of negative sentiment can elicit almost a humorous reaction, but scribes who do this do give their readers some semantically related vocabulary examples all in one spot!

NB: If interested, see my short article in Illuminations, Spring 2012, pp. 4-6, available here, for a popular presentation on colophons.

While cataloging an undated, late manuscript from Saint Mark’s Monastery (Jerusalem) today, I came across this page spread, each page showing a correction in the scribe’s hand.

SMMJ 165, ff. 6v-7r

Homer nods and copyists sleep: scribes old and new, like typesetters and typists, have been bound to occasionally slip into error, whether by letter, word, or line. Here on the right (f. 6v), four lines from the bottom, the scribe indicates that he — the odds are that the scribe was male, but it could have been a female scribe — first erroneously copied the word tešbḥātēh by transposing B and Ḥ, so it was a mistake of a letter leading to an incorrect word. On the left (f. 7r), the scribe at first omitted (probably) two lines, and he adds them into the margin. Both mistakes are signaled by a variously oriented sign similar to ÷. Although their function is not the same, it is easy to be reminded a little of the Aristarchian or Hexaplaric signs (Field, Origenis Hexaplorum quae supersunt, vol. 1, lii-lx; Swete, Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek, 69-73).

Proofreading is hardly relished by any one, whether a centuries-old scribe or today’s or tomorrow’s writer with a keyboard and screen, but seizing and adequately rectifying an error, whether by marking the error and pointing to the correction, as here, or by wholly obliterating the mistake and only giving the proper reading, at least goes a long way toward repaying the time spent doing it!