Archive for the ‘Dionysius bar Ṣalibi’ Category

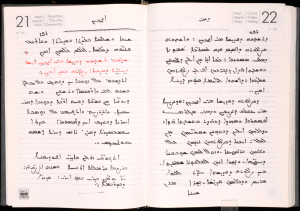

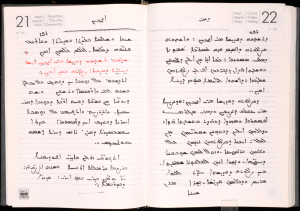

Saint Mark’s Monastery, Jerusalem, 48 is a big manuscript — 26.1x18x13.5 cm and about 600 folios — containing Dionysios bar Ṣalibi’s commentary on the Gospels, and a notable copy because it comes from only a century after the author’s death: the colophon (f. 588v) has the date Nisan 23, 1582 AG (= 1271 CE). Before the text itself begins on f. 1v, there is on the previous page a note in Garšūnī:

SMMJ 41, f. 1r

The note is not in the same hand of the manuscript’s scribe, and there is no explicit indication of its date, but it bears no marks of being recent. Here is a quickly done translation into English:

We found the date of this holy, venerated father, Mār Dionysios (that is Yaʿqub) bar Ṣalibi, recorded in the Chronicon [Ecclesiasticum] of St. Gregory Bar ʿEbrāyā, the fact that he was ordained bishop over Marʿaš by Athanasios the patriarch (that is, Yešuʿ b. Qaṭra). The ordination of Patriarch Athanasios was in the year 1450 AG (1138/9 CE), and the ordination of St. Dionysios bar Ṣalibi as bishop was in the year 1462 [AG, = 1150/1 CE]. This St. Dionysios was present at the ordination of St. Mār Michael the Great, Patriarch of Antioch, whose ordination was in the year 1478 AG [1166/7 CE] in the Monastery of Mār Barṣawmā. The eternal rest of St. Dionysios bar Ṣalibi was in Tešrin II [November] 1483 AG [= 1171 CE], and he was buried in the Church of the Virgin in Diyarbakır.

If you wish, you can read more about Dionysios bar Ṣalibi in:

- Michael the Great’s Chronicle, Edessa-Aleppo Codex, ff. 349v-350v (outer columns; = pp. 701-703 in the Gorgias Press facsimile)

- Bar ʿEbrāyā’s Chronicon [Ecclesiasticum] I 511-513, 559-561

- Assemani, Bibliotheca Orientalis II 156-211

- S.P. Brock, in GEDSH 126-127

The note above, which acknowledges Bar ʿEbrāyā as a source, apparently by an early reader, is a good example showing how manuscripts are not static objects serving merely as text-receptacles, but unique witnesses not only to this or that version of a particular text, but also to the scribes who copied them, their readers from generation to generation, and the communities that have curated them.

UPDATE: Thanks to Gabriel Rabo for pointing out a mistake in my translation due to eyeskip. It has now been corrected.

The word “manuscript” conjures images of monks, quills, parchment, candles, and the like, that is, a mostly pre-modern setting and seemingly antiquated accoutrements, but the advent and proliferation of the printing press was hardly a death knell to writing by hand, neither in the fifteenth century, nor in those following (keyboards, physical or on-screen, notwithstanding). We don’t have to go back as far as some pre-modern period in Europe or elsewhere to find manuscripts (which, remember, simply means anything written by hand) as a notable witness to scholarly, creative, or memorial activity, and we are not talking here only of texts in old (Greek, Sanskrit, etc.) or semi-old (e.g. Middle English, Ottoman Turkish) varieties of language. Consider the “papers” (in French, English, and other contemporary languages) of relatively recent authors, such as James Joyce and others, which are very often handwritten. (Following widespread use of the typewriter, typewritten pages and sometimes even electronically produced documents are sometimes misleadingly referred to as “manuscripts”!) True, these documents are typically not copied and recopied: for that, printing was employed, and sometimes — if the assumed circulation was (or, prior to efforts by publishers such as Barney Rosset of Grove Press, had to be) small — private printing, one catalog of which is here, and which on the first page has the titles Double Acrostic Enigmas, with Poetical Descriptions selected principally from British Poets and Feigned Insanity, how most usually simulated, and how best detected! From Syriac studies we may point to Gottheil’s (age 23 at the time) little book to the right. (Thankfully, many of these privately printed books are now easily available online for a wide audience.)

The word “manuscript” conjures images of monks, quills, parchment, candles, and the like, that is, a mostly pre-modern setting and seemingly antiquated accoutrements, but the advent and proliferation of the printing press was hardly a death knell to writing by hand, neither in the fifteenth century, nor in those following (keyboards, physical or on-screen, notwithstanding). We don’t have to go back as far as some pre-modern period in Europe or elsewhere to find manuscripts (which, remember, simply means anything written by hand) as a notable witness to scholarly, creative, or memorial activity, and we are not talking here only of texts in old (Greek, Sanskrit, etc.) or semi-old (e.g. Middle English, Ottoman Turkish) varieties of language. Consider the “papers” (in French, English, and other contemporary languages) of relatively recent authors, such as James Joyce and others, which are very often handwritten. (Following widespread use of the typewriter, typewritten pages and sometimes even electronically produced documents are sometimes misleadingly referred to as “manuscripts”!) True, these documents are typically not copied and recopied: for that, printing was employed, and sometimes — if the assumed circulation was (or, prior to efforts by publishers such as Barney Rosset of Grove Press, had to be) small — private printing, one catalog of which is here, and which on the first page has the titles Double Acrostic Enigmas, with Poetical Descriptions selected principally from British Poets and Feigned Insanity, how most usually simulated, and how best detected! From Syriac studies we may point to Gottheil’s (age 23 at the time) little book to the right. (Thankfully, many of these privately printed books are now easily available online for a wide audience.)

“Manuscript culture” in the fullest sense refers not to a specific time, place, or language, but to the production and re-production (i.e. copying) of manuscripts. Taken thus, it is certainly most predominant in pre-modern periods, at least in Europe, but in the Middle East and parts of Africa (Ethiopia) — what about China, India, elsewhere? — copying texts has remained, at least in some small circles, a real practice. HMML has copies of very many Gǝʿǝz manuscripts from the 20th century, and likewise for manuscripts in Syriac, Arabic, and Garšūnī. Just from Mardin, and just in Syriac, HMML has copies of more than 80 manuscripts from the 20th century. The 1960s, it seems, were a relatively active period, with some large manuscripts copied then. As my colleague Wayne Torborg pointed out, someone may have been copying the words of Genesis in Syriac while, perhaps unbeknownst to them, those words in English were being recited from Apollo 8 on Christmas Eve, 1968! While these late manuscripts may often — but hardly always! — be of limited value as textual witnesses, in terms of the manuscript as a physical product and in terms of examples of scribal activity, their worth is not at all negligible, not even to mention their colophons and readers’ notes, which are eminently unique. Also, I have talked before about the probable importance of reading handwriting (i.e. manuscripts) and practicing handwriting (copying manuscripts) in language learning (see here and here), and in the second place I pointed to certain nineteenth- and twentieth-century orientalists who seemingly used manuscript copying to good effect. So at least some manuscript copying was going on also among European scholars.

CFMM 550, dated 1945: Ibn Sīnā’s Al-Išārāt wa-l-tanbīhāt in Garšūnī with Bar ʿEbrāyā’s Syriac tr.

MGMT 81, dated 1968: Dionysios bar Ṣalibi’s Commentaries on the Old Testament

Within this context and this definition of “manuscript culture”, I would like to highlight a very recently copied manuscript from the latest batch of files from Saint Mark’s Monastery in Jerusalem. I had seen manuscripts with notes written in Syriac dated as late as 2008, and a very interesting manuscript that I doubt I shall ever forget is a collection of three saints’ lives copied into a 1993 calendar book (ZFRN 385), but based on a manuscript on parchment from 1496 AG (= 1184/5 CE)!

ZFRN 385, here the end of the Story of Mar Awgen.

As unique as that manuscript is, the great lateness of the Jerusalem manuscript (SMMJ 475) is also startlingly memorable. It has the date in three places, all from the present year, the last one being July 26, 2012! Copied by the monk, Shemun Can, at Saint Mark’s, it is a collection of Syriac poetry, mostly by later authors (but one by Jacob of Serugh and one by Ephrem), along with a few hymns in Garšūnī and the Lawij (in Kurdish with Syriac letters) of Basilios Šemʿon al-Ṭūrānī. The manuscript’s colophons are all in a style not unlike those written centuries before, and they, together with the manuscript as a whole, a physical, textual object, remind us well that manuscript culture, at least in some quarters, is alive and well.

SMMJ 475, p. 34, the beginning of Yaʿqob ʿUrdnsāyā, “On Himself”.

Alphonse Mingana, at the end of his famous article (see bibliography below) touching on those passages of the Qurʾān that show up in Dionysius bar Ṣalibi‘s (d. 1171) Response to the Arabs, briefly mentions the manuscript that is now known as Harvard Syriac 91 (then 4019; see Goshen-Gottstein, p. 74):

While the above pages were in the press, the authorities of Harvard University — to whom I here take the liberty to tender my sincerest thanks — were so kind as to place at my disposal, through the intermediary of my friend Dr. Rendel Harris, a manuscript described as “Harvard University Semitic Museum No, 4019,” and containing all the controversial works of Barsalibi mentioned by Baumstark in his Geschichte der Syrischen Literatur (p.297). This MS. formerly belonged to Dr. R. Harris in whose collection it was numbered 83. On fol. 47b we are informed that it was transcribed in Mardin, Saturday, 14th March, 1898, by the priest Gabriel, from a MS. dated 1813 of the Greeks (A.D. 1502) and written in the monastery of Mar Abel and Mar Abraham, near Midyad, in Tur ʿAbdin.

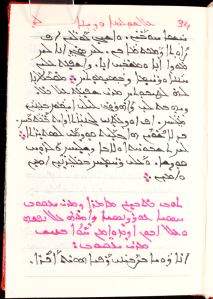

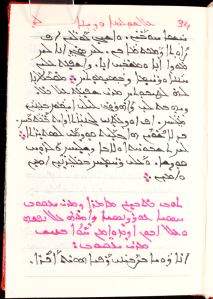

I came today in my cataloging work to the manuscript Church of the Forty Martyrs, Mardin (CFMM) 350, a large book in clear Serṭo that has the same polemical treatises of Bar Ṣalibi (Against the Arabs, Against the Jews, Against the Nestorians, Against the Chalcedonians, Against the Armenians), and I was happy to light upon a colophon at the end of memra 2 of the aforementioned treatise (p. 92, image below). The first few lines read as follows:

Let the reader pray for ʿAz(iz) — the miserable, the sinful, the weak monk, “Son of the Cross” [bar ṣlibā], monk of Midyat, from Ṭur ʿAbdin — who has copied [this book] in the Monastery of Mar Abel and Mar Abraham, the teacher of Barṣawmā, that is near the ble(ssed) city of Midyat, in the year 1813 AG, at the beginning of the month of Ēlul [September] on the memorial [lege dukrānēh] of Mar Malke of Clysma.

(See Fiey, Saints syriaques, no. 282, where one of Mar Malke’s commemoration days is given as Sept. 1.) The colophon continues with a notice of some clerical happenings of the place and time not relevant to the present focus, but those interested in early 16th-century ecclesiastical history in Ṭur ʿAbdin will probably find some things of interest and value. There are several more colophons in the manuscript (pp. 287, 307, 591, 665, 781-782), the later ones having the date 1814 AG.

CFMM 350, p. 92

It appears, then, that the manuscript before us is the one on the basis of which Harris’s late 19th-century copy, now Harv. Syr. 91, was made, and indeed a cursory look at the readings of the Harvard copy as reported by Amar confirm the fact. The manuscript was formerly at nearby Dayr Al-Zaʿfarān, as evidenced by the still present bookplate at the beginning of the codex, and Dolabani lists its contents in his catalog (olim no. 98, see pt. I, pp. 376-397). The manuscript itself has hardly been widely accessible in recent years, and Dolabani’s catalog (in Syriac), itself formerly not commonly available (but reprinted by Gorgias Press) and even where available not so usable as might be hoped for due to faults in the printing process and Dolabani’s sometimes unclear handwriting, and although the indefatigable Vööbus, of course, knew the Dayr Al-Zaʿfarān/Church of the Forty Martyrs collection well, he does not (as far as I know) make much (or any?) notice of this important manuscript. It has, however, not been wholly unknown. In the introduction to his edition of the Response to the Arabs, Joseph Amar has the following to say: “A further manuscript, Mardin Syriac 350 (unfoliated), which contains one-sentence summaries of the contents of each chapter of the treatise, has also been consulted in the preparation of this edition” (vi-vii). This statement calls for a few remarks. It must be made clear that the manuscript does have those one-sentence summaries, but this is merely the beginning of the book: the remainder of it consists of the full treatises themselves, along with some related works by other authors. The reference to this copy in his introduction is distinct from the other five manuscripts he used for his edition in that those each have a siglum, while the Mardin manuscript does not, and the latter seems to have been used in the edition much less indeed than the other manuscripts listed. He does not say how he consulted this copy (on-site in Mardin, photographs, microfilm?). The manuscript is indeed unfoliated, as he says, but at least when it was photographed by HMML in 2007, it was paginated with eastern Arabic numerals.

How CFMM 350 is related to the other witnesses to Bar Ṣalibi’s polemical treatises will require closer comparison, but it will at least displace Harv. Syr. 91 in that list, since it is the Vorlage, and its antiquity is nothing to ignore, the only older witness (only of the Response to the Arabs, not the other treatises) being Vat. Syr. 96 (Dec 1664 AG = 1352 [1325 in Amar’s ed. is an error]; Assem. Cat., p. 523), and that copy is incomplete. In terms of its text as well as some apparently contemporaneous marginal notes, CFMM 350 deserves close inspection by anyone interested in Bar Ṣalibi’s polemical treatises.

CFMM 350, p. 97, showing Qurʾān 2:31-32 in Syriac, with commentary (cf. Amar, ed. pp. 114, 116 = tr. pp. 107, 109)

Bibliography

Amar, Joseph P. Dionysius bar Ṣalībī, A Response to the Arabs. CSCO 614–615 = SS 238-239. Louvain, 2005.

Assemani, S.E. and Assemani J.S. Bibliothecae Apostolicae Vaticanae Codicum Manuscriptorum Catalogus. I.2. Rome, 1778.

Brock, S.P. “Dionysios bar Ṣalibi.” In GEDSH, 126-127. Piscataway, 2011.

Dolabani, Yuhanna. Catalogue of Syriac Manuscripts in Zaʿfaran Monastery. Dar Mardin Press, 1994; reprint, Piscataway, 2009.

Goshen-Gottstein, Moshe H. Syriac Manuscripts in the Harvard College Library: A Catalogue. Harvard Semitic Studies 23. Missoula, 1979.

Mingana, Alphonse. “An Ancient Syriac Translation of the Kur’ân Exhibiting New Verses and Variants.” Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 9 (1925): 188-235. (available as text, not PDF, here)

ADDENDUM: Barsoum (Scattered Pearls, p. 438, with n. 1) mentions CFMM 350 under the name Zaʿfaran 5 (cf. p. 428, nn. 2, 4, p. 439, n. 2).