Archive for the ‘Books’ Category

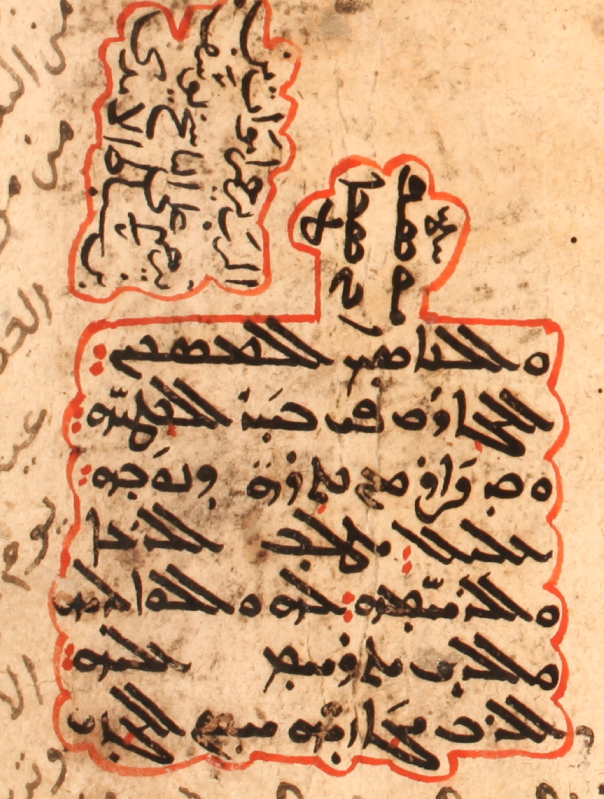

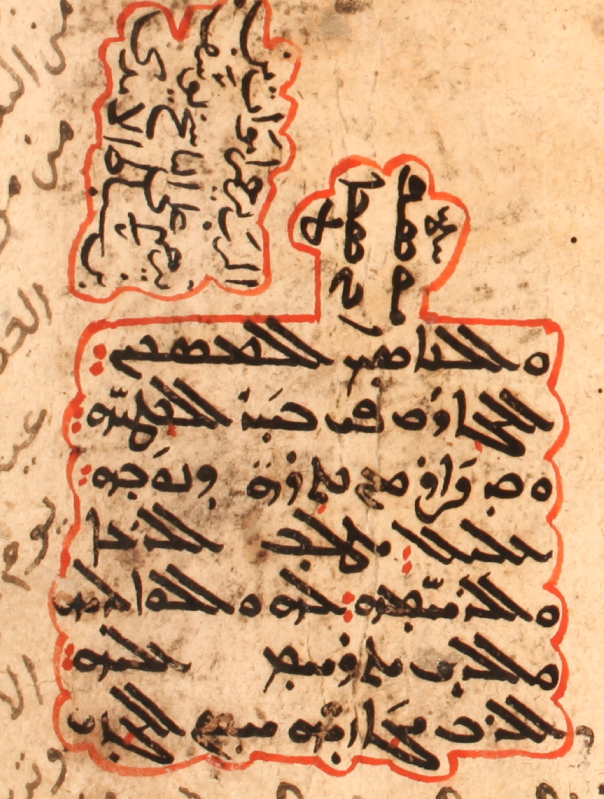

Some time ago I pointed out an Arabic/Garšūnī colophon with the phrase, “sinking in the sea of sin,” and I have since found another example from the fourteenth century (SMMJ 250, dated 1352, f. 246r, image below; sim. on f. 75r of the same manuscript).

SMMJ 250, f. 246r

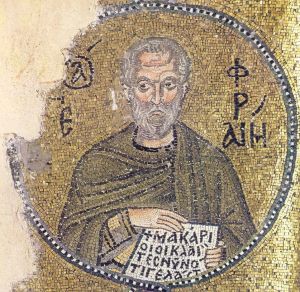

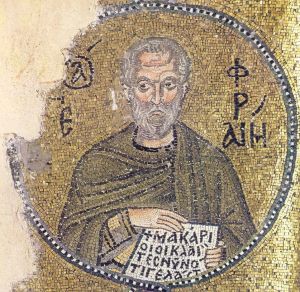

Ephrem the Syrian, Mosaic in Nea Moni, 11th cent. Source. The lines at the bottom are from Lk 6:21: “Blessed are those who weep now, because you will laugh.”

From the pen of my colleague, Edward G. Mathews, Jr., has recently appeared a little book of the collection of Armenian prayers attributed to Ephrem (vol. 4 of the Mekhitarist ed., [Venice, 1836], pp. 227-276; the prayers are also in an edition from Jerusalem [1933], and others), with Armenian text and facing English translation: The Armenian Prayers (Աղօթք) attributed to Ephrem the Syrian, TeCLA 36 (Gorgias Press, 2014). A concise and helpful introduction opens the book, and it concludes with indices for scripture and subject.

There is a lot of sin in the Armenian prayers attributed to Ephrem the Syrian. And there are a lot metaphors for sin in them, too, which may be wholesome fodder for certain classes of philologist. As I was going through this new book, it seemed like a fine idea to highlight some of the places in these ps.-Ephremian prayers that are similar to the Arabic phrase mentioned above. Some of the lines below have vocabulary similar to the “peaceful harbor” imagery that is used in colophons, on which see my paper, “The Rejoicing Sailor and the Rotting Hand: Two Formulas in Syriac and Arabic Colophons, with Related Phenomena in some Other Languages,” Hugoye 18 (2015): 67-93 (available here). This kind of language also reaches beyond biblical, patristic, and scribal texts. We hear Jean Valjean uttering “whirlpool of my sin” in “What Have I Done?” from Les Misérables.

Now for our examples from these Armenian prayers attributed to Ephrem. For these few lines I’m giving the Armenian text, Mathews’ English translation, and for fellow students of Armenian, a list of vocabulary.

I.1

…եւ ի յորձանս անօրէնութեան տարաբերեալ ծփին,

եւ առ քեզ ապաւինիմ,

որպէս Պետրոսին՝ ձեռնարկեա ինձ։

- յորձան, -աց torrent, current, whirlpool

- անօրէնութիւն iniquity, impiety

- տարաբերեմ, -եցի to shake, agitate, move, stir

- ծփեմ, -եցի to agitate, trouble

- ապաւինիմ, -եցայ to trust, rely, take refuge, take shelter

- ձեռնարկեմ, -եցի to put one’s hand to

…I am floundering and tossed about in torrents of iniquity.

But I take refuge in You,

Reach out Your hand to me as You did to Peter.

I.2

Ո՛վ խորք մեծութեան եւ իմաստութեան,

փրկեա՛ զըմբռնեալս՝

որ ի խորս մեղաց ծովուն անկեալ եմ.

- խորք, խրոց pit, depth, bottom, abyss

- փրկեմ, -եցի to save, deliver

- ըմբռնեմ, -եցի to seize, trap, catch

- մեղ, -աց sin

- ծով, -ուց sea

O depths of majesty and of wisdom,

Deliver me for I am trapped,

and I have fallen into the depths of the sea of sin.

I.7

նաւապետ բարի Յիսուս՝ փրկեա՛ զիս

ի բազմութենէ ալեաց մեղաց իմոց,

եւ տո՛ւր ինձ նաւահանգիստ խաղաղութեան։

- նաւապետ captain

- ալիք, ալեաց wave, surge, swell

- տո՛ւր impv 2sg տամ, ետու to give, provide, make

- նաւահանգիստ port, haven, harbor

- խաղաղութիւն peace, tranquility, rest, quiet

O Good Jesus, my Captain, save me

from the abundant waves of my sins,

and settle me in a peaceful harbor.

I.20

Ձգեա՛ Տէր՝զձեռս քո ի նաւաբեկեալս՝

որ ընկղմեալս եմ ի խորս չարեաց,

եւ փրկեա՛ զիս ի սաստիկ ծովածուփ բռնութենէ ալեաց մեղաց իմոց։

- ձգեմ, -եցի to stretch, extend, draw

- նաւաբեկիմ to run aground, founder, be shipwrecked

- ընկղմեմ, -եցի to sink, submerge, drown, bury

- շարիք, -րեաց, -րեօք evil deeds, iniquity; disaster

- սաստիկ, սաստկաց extreme, intense, violent, strong

- ծովածուփ tempestuous, stormy

- բռնութիւն violence, fury (< բուռն, բռանց fist, with many other derivatives)

Stretch forth, O Lord, Your hand to me for I am shipwrecked

and I am drowning in the abyss of my evil deeds.

Deliver [me] from the stormy and violent force of the waves of my sins.

I.64

Խաղաղացո՛ զիս Տէր՝ ի ծփանաց ալեաց խռովութեանց խորհրդոց,

եւ զբազմւոթեան յորձանս մեղաց իմոց ցածո՛,

եւ կառավարեա՛ զմիտս իմ ժամանել

յանքոյթ եւ ի խաղաղ նաւահանգիստն Հոգւոյդ սրբոյ։

- Խաղաղացո՛ impv 2sg խաղաղացուցանեմ, խաղաղացուցի to calm

- ծփանք wave, billow

- ձորձան, -աց current, torrent, whirlpool

- ցածո՛ impv 2sg ցածուցանեմ, ցածուցի to reduce, diminish, soften, calm, humiliate

- կառավերեմ, -եցի to guide, direct, govern

- միտ, մտի, զմտաւ, միտք, մտաց, մտօք mind, understanding

- ժամանեմ, -եցի to arrive, be able, happen

- անքոյթ safe, secure

Grant me peace, O Lord, from the billowy waves of my turbulent thoughts,

Abate the many whirlpools of my sins.

Steer my mind that it may come

To the safe and peaceful harbor of Your Holy Spirit.

In I.81, we have, not the sea, but, it seems, a river (something fordable):

Անցո՛ զիս Տէր՝ ընդ հուն անցից մեղաց…

- Անցո՛ impv 2sg անցուցանեմ, անցուցի to cause to pass, carry back, transmit

- հուն, հնի ford, shallow passage

- անցք, անցից passage, street, channel, opening

Bring me, O Lord, through the ford of the river of sins…

The sea and drowning are by no means the only metaphors for sin in these prayers. Others from pt. I include ice (15), dryness (21), thorn (23; also p. 120, line 8), sleep (25), darkness (39, 102), nakedness (44-45), bondage and prison (54, 93), a quagmire (62), an abyss (71), “dung and slime” (72), and a weight and burden (123, 125, 129). From pt. III, p. 106, ll. 29-30:

հա՜ն զիս ի տղմոյ անօրէնութեան իմոյ,

զի մի՛ ընկլայց յաւիտեան։

- հա՜ն impv 2sg հանեմ, հանի to remove, dislodge, lift up

- տիղմ, տղմոյ mire, mud, filth

- ընկլայց aor subj m/p 1sg ընկլնում, -կլայ (also ընկղմիմ, -եցայ!) to founder, sink, be plunged

- յաւիտեան, -ենից eternity

Remove me from the mire of my iniquity

lest I sink in forever.

Metaphors from nature for things other than sin are “the ice of disobedience,” “the fog of mistrust,” “the raging torrents of desires for pleasures,” and ” the spring of falsehood” in pt. VI, p. 136, ll. 23-26.

Whether these places are of interest to you spiritually, conceptually, philologically, or some combination of those possibilities, I leave you to ponder them.

I’ve been reading lately through Michael E. Stone, Adam and Eve in the Armenian Traditions, Fifth through Seventeenth Centuries, Early Judaism and its Literature 38 (Atlanta, 2013), a thick volume that collects, in Armenian and English, references to Adam & Eve, the serpent, the Garden of Eden, etc., from over a millennium of Armenian literature. There are, of course, very many interesting passages that students of the history of biblical interpretation, patristics, and Armenian will appreciate. Especially for the last named group, students of Armenian, here are a few lines of a love poem by Grigoris Ałt’amarc’i (1480-1544), kat’ołikos from 1510 (see Stone, p. 688). Stone (p. 636) publishes the lines from Mayis Avdalbegyab, Գրիգորիս Աղթամարցի, XVI դ. Ուսումնասիրություն, քննական բնագրեր եւ ծանոթություններ (Grigoris Ałt’amarc’i: Study, Critical Texts, and Commentary) (Erevan, 1963), which I do not have access to. These are apparently lines 215-218 from the poem. These lines rhyme in -ին.

Թէ տեսանեմ ըզքեզ կրկին,

Լուսաւորի միտքս իմ մթին,

Եւ տամ համբոյր շրթանց քոյին,

Նա վերանամ ես ի յԱդին։

Vocabulary:

- տեսանեմ, տեսի to see

- կրկին doubly, again

- լուսաւոեմ, -եցի to illuminate, brighten

- միտք, մտաց, մտօք mind

- մթին gloomy, dark

- տամ, ետու to give

- համբոյր, -բուրից kiss (cf. Geo. ამბორი)

- շուրթն, շրթան, շրթունք, -թանց lip

- քոյին a longer form of քո

- վերանամ, -ացայ to rise, ascend, leave

Here is Stone’s translation:

If I see you again,

My dark mind is illuminated,

And I give a kiss to your lips,

Indeed I ascend to Eden.

12th-cent. mosaic in Basilica di San Marco, Venice. Source.

A couple of days ago UPS delivered a box with copies of my new book on two homilies by Jacob of Serug. These homilies are on the Temptation of Jesus (Mt 4:1-11, Mk 1:12-13, Lk 4:1-13), and the book, my second contribution (the first is here) to Gorgias Press’ series for Jacob within Texts from Christian Late Antiquity (TeCLA), includes vocalized Syriac text with facing English translation, introduction, and a few notes. As far as I know, neither homily has been translated before, so hopefully, even with some inevitable imperfections in this first translation, they will both now meet with more readers. The introduction has a few words about manuscripts, broader history of the interpretation of the pericopes on the Temptation, and the Syriac vocabulary Jacob uses for fighting, humility, and the devil.

And for your viewing pleasure, in addition to the one above, here is another representation of the encounter between Satan and Jesus, this one from Vind. Pal. 1847, a German Prayer Book dated 1537 (more info here, and on the image here), a copy of which is available through HMML. (Two more related images from Vivarium I would highlight are this one, with the image of the devil smudged, and this one from the Moser Bible, with a very different kind of Satan.)

Temptation of Jesus. Vind. Pal. 1847, f. 18v. See further here.

Finally, from Walters 539, an Armenian Gospel-book from 1262, here is Jesus post temptation, being ministered to by angels. The text on this page is Mt 4:8b-411.

Walters 539, p. 52.

Well over two years ago I wrote a short post on some Old Nubian resources. Giovanni Ruffini has recently announced more work in general Nubian studies. These, three in number, are:

So, even though the corpus of Old Nubian is comparatively small, it’s exciting to see new work appearing widely available in this and related fields. Go have a look.

As rightly locating multi-volume sets at archive.org and other repositories of scanned books is sometimes maddening, here’s a list of the volumes of the Leiden ed. of Al-Ṭabari, edited by M. de Goeje et al., that I’ve been able to find at archive.org.

On the History, see EI² 10: 13-14. The continuation, the Ṣila of ʿArīb b. Saʿd al-Qurṭubī, was also edited by De Goeje: Arîb Tabari Continuatus (Brill, 1897) at https://archive.org/details/ilattrkhalabar00agoog. (There were other continuations, too.) NB De Goeje’s Selections from the Annals of Tabari in (1902) Brill’s Semitic Study Series (https://archive.org/details/selectionsfroman00abaruoft).

A few words on the Persian adaptation, very important due to its age and manuscript attestation. The Persian adaptation is the work of the Sāmānid vizier Abū ʿAlī Muḥammad al-Balʿamī (EI² 1: 984-985). The Persian text was published in Lucknow 1874, of which I can find no version online, and there have been more recent editions published in Iran (see esp. Daniel’s article). From Persian the text was translated into Turkish. Incidentally, the beginning of a manuscript of the Persian text is at http://www.wdl.org/en/item/6828/. Here are a few resources:

- Zotenberg’s French translation of the Persian text, Chronique de Abou-Djafar-Moʻhammed-ben-Djarir-ben-Yezid Tabari (1867-1874), is at archive.org (vol. 1, 2, 3, 4)

- Rieu, Cat. Pers. BL, I. 69

- (briefly) p. xxii of the Intro. volume to the De Goeje’s Leiden ed.

- G. Lazard, La langue des plus anciens monuments de la prose persane (Paris, 1963), 38-41.

- E.L. Daniel, “Manuscripts and Editions of Balʿamī’s Tarjamah-i tārīkh-i Ṭabarī,” JRAS (1990): 282-308.

- Andrew Peacock, Mediaeval Islamic Historiography and Political Legitimacy: Bal’amī’s Tārīkhnāma (Routledge, 2007)

Title page to the Leiden edition.

Prima Series

I 1879-1881 Barth https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal01abaruoft

II 1881-1882 Barth and Nöldeke https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal02abaruoft

III 1881-1882 Barth and Nöldeke https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri02unkngoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal03abaruoft)

IV 1890 De Jong and Prym https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri02goejgoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal04abaruoft)

V 1893 Prym https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri02guyagoog (another at https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri01unkngoog, https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal05abaruoft)

VI 1898 Prym https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri00goejgoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal06abaruoft)

X 1896 Prym https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri04unkngoog

Secunda Series

I 1881-1883 Thorbecke, Fraenkel, and Guidi https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri00unkngoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal07abaruoft)

II 1883-1885 Guidi https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri03unkngoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal08abaruoft)

III 1885-1889 Guidi, Müller, and De Goeje https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal09abaruoft

Tertia Series

I 1879-1880 Houtsma and Guyard https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal10abaruoft

II 1881 Guyard and De Goeje https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal11abaruoft

III 1883-1884 Rosen and De Goeje https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal12abaruoft

IV 1890 De Goeje https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri00bargoog (another at https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri01goejgoog, https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal13abaruoft)

________

1901 Intro., Gloss., etc. https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri01guyagoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal15abaruoft)

1901 Indices https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri00guyagoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal14abaruoft)

________

It’s probable that I’ve missed some of those that are available, and as I find or am informed of others, I’ll update this list.

For this simple post, I just want to share a few lines from a memorable scene in the Life of the famous Ethiopian saint Täklä Haymanot (ተክለ፡ ሃይማኖት፡; BHO 1128-1134). It comes from the Däbrä Libanos version, as published by Budge (1906); for more details on this and the other versions, see Denis Nosnitsin in Enc. Aeth. 4: 831-834. For the setting: the people of a “high mountain” called Wifat (ዊፋት፡) are responding to the saint’s question of how they know when their god is coming to them.

ወይቤልዎ ፡ ይመጽአ ፡ እንዘ ፡ ያንጐደጕድ ፡ ከመ ፡ ነጐድጓደ ፡ ክረምት ፡ለቢሶ ፡ እሳት። ወተፅዒኖ ፡ ዝዕበ ፡ ወብዙኃን ፡ መስተፅዕናነ ፡ አዝዕብት ፡ እምለፌ ፡ ወእምለፌ ፡ የዐውድዎ ፡ ወኵሎሙ ፡ ያበኵሁ ፡ እሳተ ፡ እምአፉሆሙ።

f. 67ra-67rb (text in Budge, vol. 2, p. 39)

My translation (for Budge’s, see vol. 1, p. 97):

And they said to him, “He comes thundering like the thunder of the rainy season, clothed in fire, riding on a jackal, and many jackal-riders surround him on each side, all of the [mounts] blowing fire out of their mouths.

Notes:

- ክረምት፡ the rainy season is June/July-September

- ዝእብ፡ (pl. አዝእብት፡) jackal; hyena; wolf. Specific possibilities include:

- Budge’s text mistakenly has መስተፅናነ፡ for the correct reading መስተፅዕናነ፡.

- The text could mean that the jackal-riders are breathing out fire, but the image in the manuscript (BL Or. 728; see Budge’s pl. 38) obviously takes that predicate as referring to the jackals themselves.

Pl. 38 from Budge, Life of Takla Haymanot, vol. 1

I’ve recently finished David B. Honey’s Incense at the Altar: Pioneering Sinologists and the Development of Classical Chinese Philology, AOS Series 86 (New Haven: AOS, 2001), which my friend Chuck Häberl pointed out to me a few months ago. The books covers the lives and works of these “pioneering sinologists” from various countries, backgrounds, and temperaments in what was for me a delightful reading experience.

While I’ve not mentioned Chinese here before, the study of Classical Chinese language, literature, and history developed, not surprisingly, along lines partly analogous to the study of other such fields, including the textual matrices and complexes frequently touched on at hmmlorientalia. Among the scholars discussed in Honey’s book is Vladivostok-born Peter Boodberg (1903-1972), and for now I’d just like to quote part of the latter’s “Philologist’s Creed,” which Honey gives in full (pp. 305-306). It’s a testament of Boodberg’s approach to philology (not only Chinese), his “brooding humanism” (Honey, p. 306), penned in a confessional tone (with echoes of the language of Qohelet in one part), and the excerpt given here (and the whole of it) might resonate — even if wryly! — with other students and scholars.

I mind me of all tongues, all tribes, and all nations that labored and wrought all manner of works with their hands, and their minds, and their hearts. And I cast mine yes unto Hind, unto Sinim, and the lands of Gogs and Magogs of the earth, across wilderness, pasture, and field, over mountains, waters, and oceans, to wherever man lived, suffered, and died; to wherever he sinned, and toiled, and sang. I rejoice and I weep over his story and relics, and I praise his glory, and I share his shame.

For Valentine’s Day, there may be no better Georgian text to turn to than the Visramiani, the Georgian version of the Persian poem Vis o Rāmin. In addition to the prose version, there is an adaptation in verse, both fortunately available at TITUS. Here is where Ramin happens to see the face of Vis, and what the sight does to him, from ch. 12 of the prose version (p. 61, ll. 19-24 in the edition of Gvakharia and Todua).

ანაზდად ღმრთისა განგებისაგან ადგა დიდი ქარი და მოჰგლიჯა კუბოსა სახურავი ფარდაგი. თუ სთქუა, ღრუბლისაგან ელვა გამოჩნდა ანუ ანაზდად მზე ამოვიდა: გამოჩნდა ვისის პირი და მისისა გამოჩენისაგან დატყუევდა რამინის გული. თუ სთქუა, გრძნეულმან მოწამლა რამინ, რომელ ერთითა ნახვითა. სული წაუღო.

Suddenly, by the providence of God, a great wind arose, and it tore the covering curtain of the sedan chair: as if lightning shone forth from a cloud, or the sun suddenly arose, the face of Vis appeared, and at her appearance the heart of Ramin was taken captive, as if a sorcerer had poisoned him; at one look he had his soul taken away. [Adapted from Wardrop’s ET, p. 50]

Some vocabulary

- ანაზდად all of a sudden

- განგებაჲ guidance, direction, decision, order

- ადგომა to arise (ადგა)

- ქარი wind

- მოგლეჯა to tear, rip (მოჰგლიჯა)

- კუბოჲ sedan chair

- სახურავი covering

- ფარდაგი curtain

- ღრუბელი cloud (ღრუბლისაგან)

- ელვაჲ lightning

- გამოჩინება to appear (გამოჩნდა)

- მზეჲ sun

- ამოსლვა to come up (ამოვიდა)

- დატყუენვა to apprehend, usurp, conquer (დატყუევდა) (cf. Šaniże, Gramm., § 22 for ვ after a consonant, and § 27 for the falling away of ნ)

- გრძნეული magician, sorcerer, witch

- მოწამვლა to poison (მოწამლა) (cf. მოწამლეჲ sorcerer)

- ნახვაჲ sight, glimpse

- წაღება to take away (წაუღო)

Even after this, the narrator continues for many lines describing the ravishing and intoxicating effect on Ramin of having seen Vis, but the few lines here and the supplied vocabulary will have to serve us for now.

Bibliography

*See further bibliography at Giunashvili 2013.

Gippert, J. (1994). Towards and Automatical Analysis of a Translated Text and its Original: The Persian Epic of Vīs u Rāmīn and the Georgian Visramiani. Studia Iranica, Mesopotamica et Anatolica, 1, 21–59.

Giunashvili, J. (2013). Visramiani. In Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved from http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/visramiani

Gvakharia, A. (2001). Georgia iv. Literary Contacts with Persia. In Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved from http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/georgia-iv–1

Lang, D. M. (1963). Rev. of Alexander Gvakharia and Magali Todua, Visramiani (The Old Georgian Translation of the Persian Poem Vis o Ramin): Text, Notes, and Glossary. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 26(2), 480.

Vashalomidze, S. G. (2008). Ein Vergleich georgischer und persischer Erziehungmethoden anhand literarischer Quellen der Hofliteratur am Beispiel von Vīs u Rāmīn und Visramiani. In A. Drost-Abgarjan, J. Kotjatko-Reeb, & J. Tubach (Eds.), Von Nil an die Saale: Festschrift für Arafa Mustafa zum 65. Geburtstag am 28. Februar 2005 (pp. 463–480). Halle (Saale). Retrieved from http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/642205

Wardrop, O. (1914). Visramiani: The Story of the Loves of Vis and Ramin, a Romance of Ancient Persia (Vol. 23). London: Royal Asiatic Society. Retrieved from http://gwdspace.wrlc.org:8180/xmlui/handle/38989/c011c5b27

I have spoken here before of my love of chrestomathies, with which especially earlier decades and centuries were perhaps fuller than more recent times. (I don’t know how old the word “chrestomathia” and its forms in different languages is, but the earliest use in English that the OED gives is only from 1832. We may note that, at least in English, the word has been extended to refer not only to books useful for learning another language, but simply to a collection of passages by a specific author, as in A Mencken Chrestomathy.) Chrestomathies may — and I really do not know — strike hardcore adherents to the latest and greatest advice of foreign language pedagogy as quaint and sorely outdated, my own view is that readers along these lines — text selections, vocabulary, more or less notes on points of grammar — can be of palpable value to students of less commonly taught languages, especially for those studying without regular recourse to a teacher. Since I’m talking about reading texts, I have in mind mainly written language and the preparation of students for reading, but that does not, of course, exclude speaking and hearing: those activities are just not the focus.

I have gone through seventy-one chrestomathies from the nineteenth to the twenty-first centuries in several languages (Arabic, Armenian, Coptic, Syriac, Georgian, Old Persian, Middle Persian, Old English, Middle English, Middle High German, Latin, Greek, Akkadian, Sumerian, Ugaritic, Aramaic dialects, &c.). The data (not absolutely complete) is available in this file: chrestomathy_data. By far the commonest arrangement is to have all the texts of the chrestomathy together, with or without grammatical or historical annotations, and then the glossary separately, and in alphabetical order, at the end of the book (or in another volume). Notable exceptions to this rule are some volumes in Brill’s old Semitic Study Series, Clyde Pharr’s Aeneid reader, and the JACT’s Greek Anthology, which contain a more or less comprehensive running vocabulary either on the page (the last two) or separately from the text (the Brill series). Some chrestomathies have no notes or vocabulary. These can be useful for languages that have hard-to-access texts editions or when the editor wants to include hitherto unpublished texts, but the addition of lexical and grammatical helps would even in those cases add definite value to the work for students.

In addition to these printed chrestomathies, there are some similar electronic publications, such as those at Early Indo-European Online from The University of Texas at Austin, which give a few reading texts for a number of IE languages: the texts are broken down into lines, each word is immediately glossed, and an ET is supplied, with a full separate glossary for each language.

From a Greek reader I have been putting together off and on.

Over the years, I have made chrestomathy texts in various languages, either for myself or for other students, and more are in the works. (Most are unpublished, but here is one for an Arabic text from a few years ago.) I have used different formats for text, notes, and vocabulary, and I’m still not decided on what the best arrangement is.

This little post is not a full disquisition on the subject of chrestomathies. I just want to pose a question about the vocabulary items supplied to a given text in a chrestomathy: should defined words be in the form of a running vocabulary, perhaps on the page facing the text or directly below the text, or should all of the vocabulary be gathered together at the end like a conventional glossary or lexicon? What do you think, dear and learned readers?

For some brief Friday fun, here’s part of a colophon that shows a little playful cleverness from a scribe. The manuscript CCM 58 (olim Mardin 7), a New Testament manuscript dated July 2053 AG (= 1742 CE) and copied in Alqosh, has a long colophon, including the following few colorful (literally and figuratively) lines near the end, at the bottom of one page and the top of the next:

CCM 58, f. 227v

CCM 58, f. 228r

That is:

Lord, may the payment of the five twins that have toiled, worked, labored, and planted good seed in a white field with a reed from the forest not be refused, but may they be saved from the fire of Gehenna! Yes, and amen!

The “five twins” are the scribe’s ten fingers, the “good seed” is the writing, the “white field” is the paper, and the “reed” is the pen. At least some of this imagery is not unique to this manuscript. In any case we have a memorable way of thinking about a scribe’s labor.