Archive for September 2014

Many years ago I read F.F. Bruce’s In Retrospect, and among the anecdotes he relates that for some reason or other have remained in my memory is one about W.M. Edward of Leeds University. Bruce says (pp. 106-107),

My new chief, Professor W.M. Edwards of the Chair of Greek in Leeds, was an unusual man. He had been born into a military family and himself embarked on a military career, being an officer in the Royal Garrison Artillery until his later thirties. He then went to Oxford as an undergraduate, taking his B.A. at the age of forty and becoming a Fellow of Merton College the same year. Three years later he was appointed Professor of Greek in Leeds. He was an accomplished linguist, speaking Welsh, Gaelic, Russian and Hebrew as well as the commoner European languages. … On another occasion he came into my room to see me about something or other, and found me reading the Hebrew text of Judges. Immediately he threw back his head and recited in Hebrew, Samson’s song of victory, “With the jawbone of an ass…”

The Samson story is a good one, and well known. Students making their first forays into classical Hebrew prose rightly learn it thoroughly, and these two lines in verse 15:16 (בלחי החמור חמור חמרתים בלחי החמור הכיתי אלף איש), with the word play and the rhythm, make a good inhabitant of the memory’s palace. For fun, here they are in a few more languages, and some vocabulary in case students of any of these languages are reading.

Poster for Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949). Source; cf. this one.

Aramaic (Targum) בלועא דחמרא רמיתנון דגורין בלועא דחמרא קטלית אלף גברא

- לוּעָא jaw

- חמָרָא ass

- דְּגוֹר heap

Greek Ἐν σιαγόνι ὄνου ἐξαλείϕων ἐξήλειψα αὐτούς, ὅτι ἐν σιαγόνι ὄνου ἐπάταξα χιλίους ἄνδρας.

Syriac (Pesh.) ܒܦܟܐ ܕܚܡܪܐ ܟܫܝ̈ܬܐ ܟܫܝܬ ܡܢܗܘܢ. ܒܦܟܐ ܕܚܡܪܐ ܩܛܠܬ ܐܠܦ ܓܒܪ̈ܝܢ܀

- pakkā jaw, cheek

- ḥmārā ass

- kšā to pile up, heap (both verb and pass. ptcp. here)

Armenian ծնօտի́ւ իշոյ ջնջելով ջնջեցի́ զն(ո)ս(ա), զի ծնօտիւ իշոյ կոտորեցի հազա́ր այր։

- ծնօտ, -ից jaw, cheek

- իշայր, -ոյ wild ass

- ջնջեմ, -եցի to destroy, exterminate

- կոտորեմ, -եցի to shatter, destroy, massacre

- հազար thousand

Georgian (Gelati; only the first half translated, and no mention of the ass!) ღაწჳთა აღმოჴოცელმან აღვჴოცნე იგინი

- ღაწუი cheek

- აღჴოცა to kill off (participle აღმოჴოცელი and finite verb both in the sentence)

Arabic (from the London Polyglot; there are other versions)

- ṭaraḥa (a) to drive away, repel

- ʕaẓm bone

- ḫadd cheek

- ḥimār ass

- tulūl is a pl. of tall hill, but here, heap

- fakk jawbone (cf. Syriac above)

Gǝʕǝz በዐጽመ ፡ መንከሰ ፡ አድግ ፡ ደምስሶ ፡ ደምሰስክዎሙ ፡ እስመ ፡ በዐጽመ ፡ መንከሰ ፡ አድግ ፡ ቀተልኩ ፡ ዐሠርተ ፡ ምእተ ፡ ብእሴ ።

- መንከስ፡jaw, jawbone (√näkäsä to bite, like näsäkä, with cognates in many Semitic languages)

- አድግ፡ ass

- ደምሰሰ፡ to abolish, wipe out, destroy

NB: In Islamic tradition, it is not the jawbone of an ass, but that of a camel (laḥy baʕīr), that Samson employs:

وكان اذا لقيهم لقيهم بلحي بعير

(J. Barth & Th. Nöldeke, Annales quos scripsit Abu Djafar Mohammed Ibn Djarir At-Tabari, 1.II.794.7-8 [1881-1882]; available here) [More broadly, see Andrew Rippin, “The Muslim Samson: Medieval, Modern and Scholarly Interpretations,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 71 (2008): 239-253.]

I stumbled upon the sentence below in Sarjveladze and Fähnrich’s Altgeorgisch-Deutsches Wörterbuch, 1213a. (I’m told that it’s National Dog Week. If so, this is a fitting sentence to read!) It comes from Basil’s Hexaemeron, homily 9.

The Greek (ed. Giet, SC 26, 2d ed., Hom. 9.4.43) is as follows:

Λόγου μὲν ἄμοιρος ὁ κύων, ἰσοδυναμοῦσαν δὲ ὅμως τῷ λόγῳ αἴσθησιν ἔχει.

And the Georgian text (ed. Abuladze, 129.28-29) is:

ძაღლი უსიტუელ არს, არამედ აქუს მას გრძნობაჲ, რომელი შეეტყუების ძალსა სიტყჳსასა.

Vocabulary

- ძაღლი dog

- უსიტყუელი without speech, unable to speak

- აქუს to have (see previously in OGPS here and here)

- გრძნობაჲ sense, feeling

- შე-ე-ტყუებ-ი-ს 3sg pres შეტყუება to correspond to

- ძალი power, force

- სიტყუაჲ speech, language, words

Sarjveladze and Fähnrich translate, “Der Hund ist nicht fähig zu sprechen, doch er besitzt Gefühl, das der Kraft des Wortes entspricht.” In English we might say,

A dog is without the capacity to speak, but it has a faculty of perception that corresponds to the power of speech.

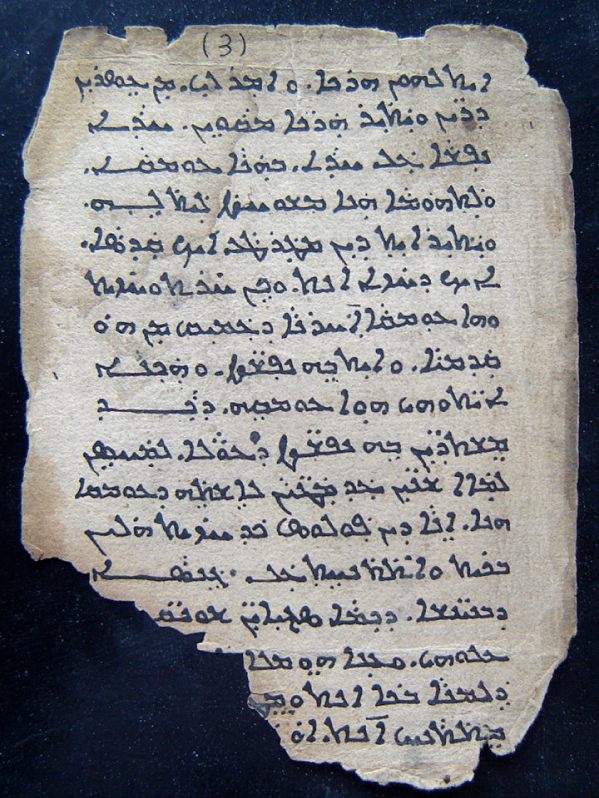

The Apocalypse of Paul (BHG 1460, CANT 325) is one of the more well known New Testament apocrypha in Syriac, with an edition and with translations into Latin, German, and English available (see bibliography below). The collection of Syriac manuscripts at the Chaldean Church of St. Joseph in Tehran, which I recently mentioned in another post, has two witnesses to the Apocalypse of Paul, one of which has been known, but the other, as far as I know, has escaped the notice of scholars who might be interested in the text.

The known copy is in manuscript № 8, a manuscript to which Alain Desreumaux (1995) has devoted an article with a detailed catalog of the texts in the manuscript. In this manuscript, the preface to the Apocalypse of Paul is on ff. 136r-140r, and the Apocalypse itself on ff. 140r-171v. (The foliation given here, based on the file names of the photographs, differs slightly from Desreumaux’s. The manuscript is not physically foliated.) Here is a folio spread from this copy (ff. 162-163r).

Tehran, St. Jos., 8, ff. 162-163r

…a servant from among the angels, and he had in his hand a pitch-fork that had three tines, and [with it] he was pulling the old man’s guts out through his mouth. … (f. 162v, lines 1-3)

The other witness, manuscript № 17, is fragmentary, consisting only of two loose and torn folios, but they are contiguous. The page numbers were marked out of order and should be read as follows: 2, 1, 4, 3. This fragment corresponds to parts of §§ 32-34 (pp. 132, 134) in the edition of Ricciotti (cf. Perkins, pp. 203-204 / Zingerle pp. 164-165 / ≈ Tischendorf pp. 57-58). In this order, then, here are the images:

p. 2 corr. to Ricciotti 132.2-132.10

p. 1 corr. to Ricciotti 132.10-132.18

p. 4 corr. to Ricciotti 132.18-132.25

p. 3 corr. to Ricciotti 132.26-29, 134.1-6

A cursory comparison with Ricciotti’s text reveals very few differences between them.

Bibliography

(see further the Comprehensive Bib. on Syriac Christianity here)

Desreumaux, Alain. “Des symboles à la réalite: la préface à l’Apocalypse de Paul dans la tradition syriaque.” Apocrypha 4 (1993): 65-82.

Desreumaux, Alain. “Un manuscrit syriaque de Téhéran contenant des apocryphes.” Apocrypha 5 (1994): 137-164.

Desreumaux, Alain. “Le prologue apologétique de l’Apocalypse de Paul syriaque: un débat théologique chez les Syriaques orientaux.” Pages 125-134 in Entrer en matière. Les prologues. Edited by Dubois, Jean-Daniel and Roussel, Bernard. Patrimoines: Religions du Livre. Paris: Cerf, 1998.

Desreumaux, Alain. “L’environnement de l’Apocalypse de Paul. À propos d’un nouveau manuscrit syriaque de la Caverne des trésors.” Pages 185-192 in Pensée grecque et sagesse d’Orient. Hommage à Michel Tardieu. Edited by Amir-Moezzi, Mohammed-Ali and Dubois, Jean-Daniel and Jullien, Christelle and Jullien, Florence. Bibliothèque de l’École des Hautes Études, Sciences religieuses 142. Turnhout: Brepols, 2010.

Perkins, Justin. “The Revelation of the Blessed Apostle Paul Translated from an Ancient Syriac Manuscript.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 8 (1866): 183-212. (available here)

Ricciotti, Giuseppe. “Apocalypsis Pauli syriace.” Orientalia NS 2 (1933): 1-25, 120-149. [ed. of Vat. Syr. 180 and Vat. Borg. Syr. 39, with facing LT]

Zingerle, Pius. “Die Apocalypse des Apostels Paulus, aus einer syrischen Handschrift des Vaticans übersetzt.” Vierteljahrsschrift für deutsch- und englisch-theologische Forschung und Kritik 4 (1871): 139-183. [tr. on the basis of Vat. Syr. 180] (available here)

The poem below is one of Heimweh. The poetess credited with the poem, whether rightly or wrongly, is Maysūn bint Baḥdal b. Unayf al-Kalbiyya, the mother of Yazīd I and wife of Muʿāwiya, and she is said to have sung these lines after her husband brought her to Syria (al-Šām) from the desert home of her family. She came from a tribe predominantly Christian. (See the brief article about her by Lammens in EI² 6: 924. On her father, Baḥdal, see EI² 1: 919-920.) After the Arabic text, an English translation follows, together with a list of some vocabulary.

The poem’s rhyme-letter (rawī) is f, which is preceded by ī or ū, these two vowels being considered as rhyming (Wright, Grammar of the Arabic Language, vol. 2, § 196b). The text of the poem is given in Nöldeke-Müller, Delectus veterum carminum arabicorum, Porta Linguarum Orientalium 13 (Berlin, 1890), p. 25, and in Heinrich Thorbecke’s edition of Al-Ḥarīrī’s (EI² 3: 221-222) Durrat al-ġawwāṣ fī awhām al-ḫawwāṣ (Leipzig, 1871), pp. 41-42. (Nöldeke and Müller dedicated their Delectus to the memory of the recently departed Thorbecke.) The images below are from the latter book.

English’d:

Aye, dearer to me is a tent where the winds roar than a lofty palace.

Dearer to me is a rough woolen cloak with a happy heart than clothes of well-spun wool.

Dearer to me is a morsel of food at the side of the tent than a cake to eat.

Dearer to me are the sounds of winds in every mountain path than the tap of the tambourine.

Dearer to me is a dog barking at my night visitors than a familiar cat.

Dearer to me is a young, unyielding camel following a litter than an active mule.

And dearer to me is a thin generous man from among my cousins than a strong lavishly fed man.

Vocabulary and notes:

- ḫafaqa i to beat; (of wind) to roar

- qaṣr citadel, palace (on which see Jeffery, Foreign Vocabulary of the Qurʾān, 240)

- munīf lofty, sublime, projecting

- ʿabāʾa cloak made of coarse wool

- qarra a i to be cool; with ʿayn eye, to be joyful, happy (Lane 2499c)

- šaff a garment of fine wool

- kusayra (dimin.) a small piece of something

- kisr side (of a tent). Note in this line the jinās, the use of two words of the same root but different meaning (see Arberry, Arabic Poetry, 21-23).

- raġīf cake

- faǧǧ wide path in the mountains

- naqr beat, crack, tap

- duff tambourine

- ṭāriq, pl. ṭurrāq someone who comes at night

- dūn here, before, opposite (Lane 938c)

- alūf familiar, sociable

- bakr young camel

- ṣaʿb difficult, unyielding

- baġl mule

- zafūf agile, active, quick

- ẓaʿīna a woman’s litter carried by camels

- ḫirq liberal, generous, bountiful

- naḥīf thin, slight, meager

- ʿilǧ “strong, sturdy man” (Lane)

- ʿalīf fatted, stuffed, fed

In a recent post, I mentioned Bar Bahlul’s source “the Proverbs [or tales] of the Arameans”. Among other entries in his lexicon where he cites that source, here is another:

Bar Bahlul, Lexicon, ed. Duval, col. 2072

English’d:

Tmirā I found it in the Proverbs [or tales] of the Arameans. I think it is tatmīr, that is, seasoned, salted meat.

Here is an image from a manuscript of the Lexicon, SMMJ 229 (dated 2101 AG = 1789/90 CE), f. 311v:

SMMJ 229, f. 311v

This is not a particularly special copy of the Lexicon; it’s just one I had immediately at hand. It is, not surprisingly, slightly different from Duval’s text, including the variants he gives. Note that the Persian word at the end is misspelled in this copy.

Payne Smith (col. 4461) defines tmirā as caro dactylis condita (“meat seasoned with dates”), with Bar Bahlul cited, along with some variation in another manuscript, including alongside tatmīr the word تنجمير. I don’t know anything certain about this additional word (rel. to Persian tanjidan, “to twist together, squeeze, press”?).

The word tatmīr is a II maṣdar of the root t-m-r, which has to do with dates. The Arabic noun is tamr (dried) dates (do not confuse with ṯamar fruit), and probably from Arabic Gǝʿǝz has ተምር፡; cf. Heb. tāmār, JPA t(w)mrh, Syr. tmartā, pl. tamrē. (Another Aramaic word for date-palm is deqlā.) The Arabic D-stem/II verb tammara means “to dry” (dates, meat) (Lane 317). While the noun tamr means “dates”, the verb tammara does not necessarily have to do with drying dates, but can also refer to cutting meat into strips and drying it. Words for tatmīr in the dictionary Lisān al-ʿarab are taqdīd, taybīs, taǧfīf, tanšīf; we find the description taqṭīʿu ‘l-laḥmi ṣiġāran ka-‘l-tamri wa-taǧfīfuhu wa-tanšīfuhu (“cutting meat into small pieces like dates, drying it, and drying it out”) and further, an yaqṭaʿa al-laḥma ṣiġāran wa-yuǧaffifa (“he cuts meat into small pieces and dries it”). All this makes it doubtful that the word above in Bar Bahlul’s lexicon really has anything to do with dates. Why not simply “dried, seasoned meat”?

As for the passive participle mubazzar, b-z-r is often “to sow”, but may also be used for the “sowing” of seeds, spices, etc. in cooking, so: “to season” (Lane 199). Finally, the last word is Persian namak-sud “salted” (Persian [< Middle Persian] namak salt + sudan to rub [also in Mid.Pers.)

Below is Lk 12:27 in the Adishi text. A comparison with this verse as it appears in the xanmeti manuscript A-844, the Pre-Athonite version, and the Athonite version reveals only minor differences, two of which are mentioned below.

κατανοήσατε τὰ κρίνα πῶς αὐξάνει· οὐ κοπιᾷ οὐδὲ νήθει· λέγω δὲ ὑμῖν, οὐδὲ Σολομὼν ἐν πάσῃ τῇ δόξῃ αὐτοῦ περιεβάλετο ὡς ἓν τούτων.

განიცადენით შროშანნი, ვითარ-იგი აღორძნდის: არცა შურებინ, არცა სთავნ. ხოლო გეტყჳ თქუენ, რამეთუ არცა სოლომონ ყოველსა დიდებასა მისსა შეიმოსა, ვითარცა ერთი ამათგანი.

- გან-ი-ცად-ენ-ი-თ aor impv 2pl განცდა to see, look at

- შროშანი lily (cf. Armenian շուշան [this verse begins Հայեցարուք ընդ շուշանն], Syr. šuša(n)tā, etc.)

- აღორძნ-დ-ი-ს aor iter 3sg აღორძინება to grow

- შურ-ებ-ი-ნ pres iter 3sg შურება to hurry; suffer (the other versions have შურების pres 3sg)

- სთავ-ნ pres iter 3sg სთვა to spin (the other versions have სთავს pres 3sg)

- გ-ე-ტყ-ჳ pres 1sg O2 სიტყუა to say

- შე-ი-მოს-ა aor 3sg შემოსა to clothe, put on

Here are three exclamatory sentences, one from the Sinai Mravaltavi (Polycephalion) and two from the Georgian version of Chrysostom’s homilies on Matthew, all with similar vocabulary.

ჵ ახალი და დიდებული საქმჱ! Sinai Mravaltavi, 39 (p. 219.17; f. 208r)

O new and excellent thing!

ჵ, ახალი იგი და დიდებული საკჳრველი! Chrysostom, Hom. Mt., hom. 75 (p. 302.27), [on Mt 24:15]

Ὤ καινῶν καὶ παραδόξων πραγμάτων! PG 58.699 (NB singular in Georgian, plural in Greek)

O that new and excellent marvel!

ეჰა, საკჳრველი ახალი და დიდებული, და ჭეშმარიტად სასწაული დიდისა ძლევისაჲ! Chrysostom, Hom. Mt., hom. 87 (p. 433.29-30)

(I do not immediately see anything corresponding to this in the Greek of PG 58.)

Look! A new and excellent marvel, and truly a sign of great power!

Vocabulary

- ახალი new

- დიდებული excellent, fabulous, great, fantastic, terrific, superb

- ჭეშმარიტად truly

- საკჳრველი wonderful, astonishing

- სასწაული wonder, sign

- ძლევაჲ power

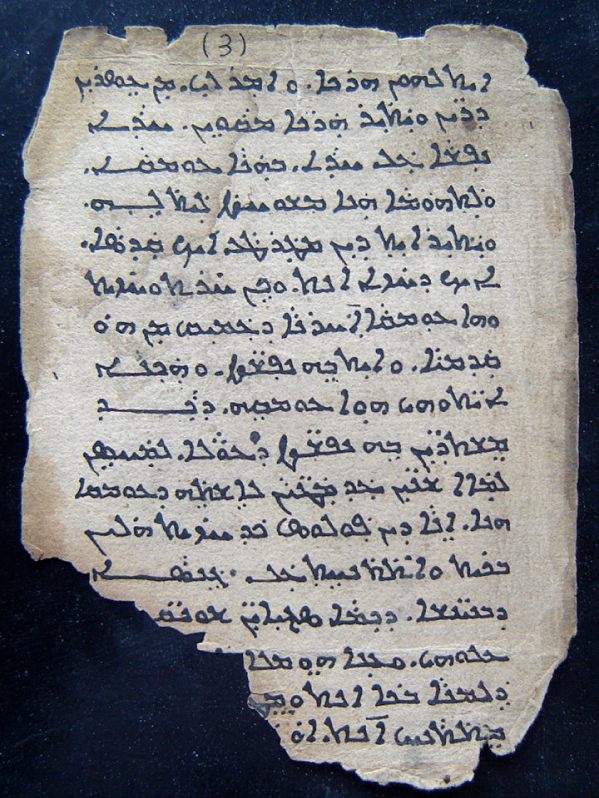

Among the few manuscripts of the Chaldean Church of St. Joseph in Tehran is a late (1896), huge codex (№ 5) with 71 memre of Narsai. A typewritten note by Ph. Gignoux (dated Mar 23, 1966) accompanies the book, saying that it is a copy of BL Or 5463 (on which see Margoliouth, Descriptive List, pp. 49-50), which is dated 1893 and was copied in Urmi. (In his edition of the homilies of Narsai on creation, Gignoux calls this manuscript Téhéran № 1 and uses the siglum F; see PO 34: 520 [102].) At the beginning of the book is a very interesting note in Syriac that was written some time after 1965.

![Tehran, Chaldean Church of St. Joseph, № 5, p. [iii]](https://hmmlorientalia.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/tehran_st_jos_5_note.png?w=1000)

Tehran, Chaldean Church of St. Joseph, № 5, p. [iii]

Transliteration (with vowels):

zebnet l-aṣṣaḥtā hādē d-mēmrē d-narsay ʿam ʿesrā ṣḥāḥē (ʾ)ḥrānē ktibay idā menhon ḥdattā mšamlaytā d-dārā da-tlāt-ʿsar w-hākwāt orāytā d-yattir qallil d-hu kad hu zabnā. d-šaddret enon l-bēt arkē d-watiqan l-appay šnat 1965 l-māran men gabrā ihudāyā ba-šmā d-sulaymān ahron [hārūn?] d-ḥānutēh simā (h)wāt qallil l-ʿel men l-qublā d-izgaddutā d-england da-b-plaṭṭiā d-ferdawsi b-tehran mdi(n)tā

✝ yoḥannān simʿān ʿisāy

miṭropoliṭa d-kaldāyē d-tehran [transp.]

English translation:

I bought this copy of the homilies of Narsai together with ten other manuscripts — including a complete New Testament of the thirteenth century, and similarly an Old Testament, more or less of the same time, which I sent to the Vatican Library — about the year 1965 AD from a Jewish man named Solomon Aaron, whose shop is situated a little up and across from the English embassy on Ferdowsi Avenue in Tehran.

Yoḥannān Simʿān ʿIsāy

Metropolitan of the Chaldeans of Tehran

[Thanks to Grigory Kessel for the suggestion that watiqan refers to the Vatican Library.]

For some photos along Ferdowsi Avenue, including an old picture of the British embassy, see here. It is unknown exactly where the bookseller’s shop was located, but both the church and the embassy are easily discovered on the map:

As rightly locating multi-volume sets at archive.org and other repositories of scanned books is sometimes maddening, here’s a list of the volumes of the Leiden ed. of Al-Ṭabari, edited by M. de Goeje et al., that I’ve been able to find at archive.org.

On the History, see EI² 10: 13-14. The continuation, the Ṣila of ʿArīb b. Saʿd al-Qurṭubī, was also edited by De Goeje: Arîb Tabari Continuatus (Brill, 1897) at https://archive.org/details/ilattrkhalabar00agoog. (There were other continuations, too.) NB De Goeje’s Selections from the Annals of Tabari in (1902) Brill’s Semitic Study Series (https://archive.org/details/selectionsfroman00abaruoft).

A few words on the Persian adaptation, very important due to its age and manuscript attestation. The Persian adaptation is the work of the Sāmānid vizier Abū ʿAlī Muḥammad al-Balʿamī (EI² 1: 984-985). The Persian text was published in Lucknow 1874, of which I can find no version online, and there have been more recent editions published in Iran (see esp. Daniel’s article). From Persian the text was translated into Turkish. Incidentally, the beginning of a manuscript of the Persian text is at http://www.wdl.org/en/item/6828/. Here are a few resources:

- Zotenberg’s French translation of the Persian text, Chronique de Abou-Djafar-Moʻhammed-ben-Djarir-ben-Yezid Tabari (1867-1874), is at archive.org (vol. 1, 2, 3, 4)

- Rieu, Cat. Pers. BL, I. 69

- (briefly) p. xxii of the Intro. volume to the De Goeje’s Leiden ed.

- G. Lazard, La langue des plus anciens monuments de la prose persane (Paris, 1963), 38-41.

- E.L. Daniel, “Manuscripts and Editions of Balʿamī’s Tarjamah-i tārīkh-i Ṭabarī,” JRAS (1990): 282-308.

- Andrew Peacock, Mediaeval Islamic Historiography and Political Legitimacy: Bal’amī’s Tārīkhnāma (Routledge, 2007)

Title page to the Leiden edition.

Prima Series

I 1879-1881 Barth https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal01abaruoft

II 1881-1882 Barth and Nöldeke https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal02abaruoft

III 1881-1882 Barth and Nöldeke https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri02unkngoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal03abaruoft)

IV 1890 De Jong and Prym https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri02goejgoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal04abaruoft)

V 1893 Prym https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri02guyagoog (another at https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri01unkngoog, https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal05abaruoft)

VI 1898 Prym https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri00goejgoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal06abaruoft)

X 1896 Prym https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri04unkngoog

Secunda Series

I 1881-1883 Thorbecke, Fraenkel, and Guidi https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri00unkngoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal07abaruoft)

II 1883-1885 Guidi https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri03unkngoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal08abaruoft)

III 1885-1889 Guidi, Müller, and De Goeje https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal09abaruoft

Tertia Series

I 1879-1880 Houtsma and Guyard https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal10abaruoft

II 1881 Guyard and De Goeje https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal11abaruoft

III 1883-1884 Rosen and De Goeje https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal12abaruoft

IV 1890 De Goeje https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri00bargoog (another at https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri01goejgoog, https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal13abaruoft)

________

1901 Intro., Gloss., etc. https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri01guyagoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal15abaruoft)

1901 Indices https://archive.org/details/annalesquosscri00guyagoog (another at https://archive.org/details/tarkhalrusulwaal14abaruoft)

________

It’s probable that I’ve missed some of those that are available, and as I find or am informed of others, I’ll update this list.

![Tehran, Chaldean Church of St. Joseph, № 5, p. [iii]](https://hmmlorientalia.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/tehran_st_jos_5_note.png?w=1000)