Archive for the ‘theology’ Tag

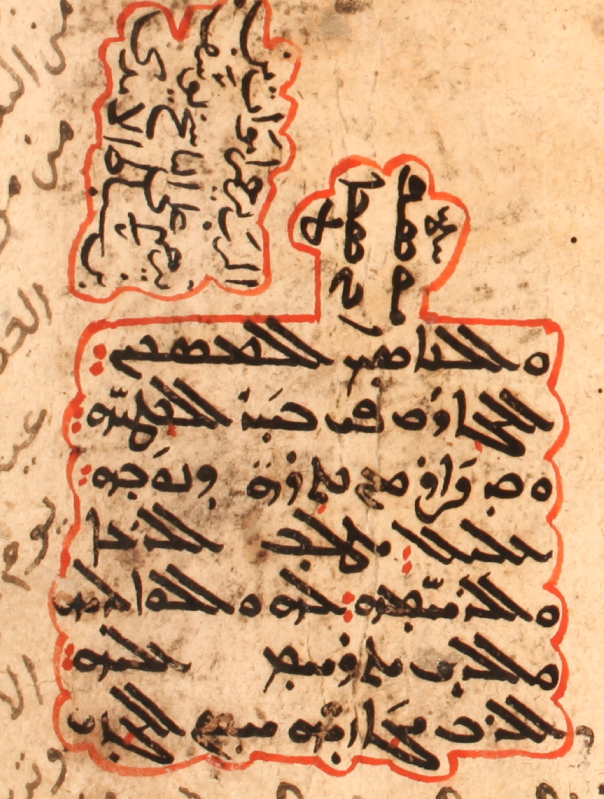

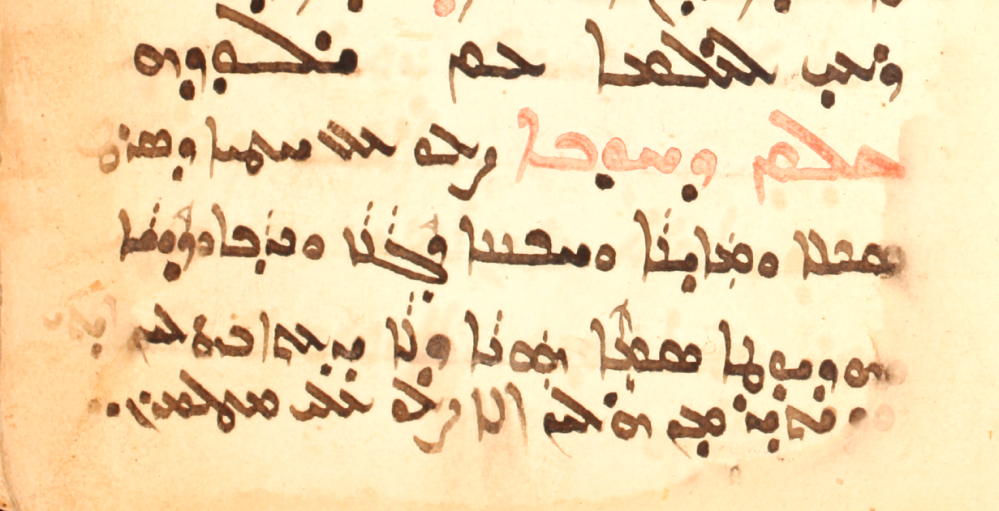

Some time ago I pointed out an Arabic/Garšūnī colophon with the phrase, “sinking in the sea of sin,” and I have since found another example from the fourteenth century (SMMJ 250, dated 1352, f. 246r, image below; sim. on f. 75r of the same manuscript).

SMMJ 250, f. 246r

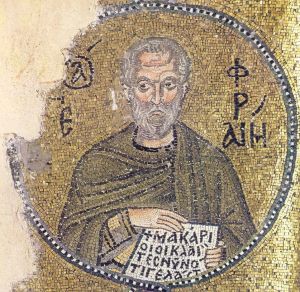

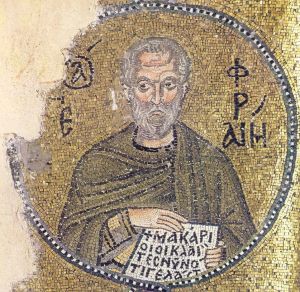

Ephrem the Syrian, Mosaic in Nea Moni, 11th cent. Source. The lines at the bottom are from Lk 6:21: “Blessed are those who weep now, because you will laugh.”

From the pen of my colleague, Edward G. Mathews, Jr., has recently appeared a little book of the collection of Armenian prayers attributed to Ephrem (vol. 4 of the Mekhitarist ed., [Venice, 1836], pp. 227-276; the prayers are also in an edition from Jerusalem [1933], and others), with Armenian text and facing English translation: The Armenian Prayers (Աղօթք) attributed to Ephrem the Syrian, TeCLA 36 (Gorgias Press, 2014). A concise and helpful introduction opens the book, and it concludes with indices for scripture and subject.

There is a lot of sin in the Armenian prayers attributed to Ephrem the Syrian. And there are a lot metaphors for sin in them, too, which may be wholesome fodder for certain classes of philologist. As I was going through this new book, it seemed like a fine idea to highlight some of the places in these ps.-Ephremian prayers that are similar to the Arabic phrase mentioned above. Some of the lines below have vocabulary similar to the “peaceful harbor” imagery that is used in colophons, on which see my paper, “The Rejoicing Sailor and the Rotting Hand: Two Formulas in Syriac and Arabic Colophons, with Related Phenomena in some Other Languages,” Hugoye 18 (2015): 67-93 (available here). This kind of language also reaches beyond biblical, patristic, and scribal texts. We hear Jean Valjean uttering “whirlpool of my sin” in “What Have I Done?” from Les Misérables.

Now for our examples from these Armenian prayers attributed to Ephrem. For these few lines I’m giving the Armenian text, Mathews’ English translation, and for fellow students of Armenian, a list of vocabulary.

I.1

…եւ ի յորձանս անօրէնութեան տարաբերեալ ծփին,

եւ առ քեզ ապաւինիմ,

որպէս Պետրոսին՝ ձեռնարկեա ինձ։

- յորձան, -աց torrent, current, whirlpool

- անօրէնութիւն iniquity, impiety

- տարաբերեմ, -եցի to shake, agitate, move, stir

- ծփեմ, -եցի to agitate, trouble

- ապաւինիմ, -եցայ to trust, rely, take refuge, take shelter

- ձեռնարկեմ, -եցի to put one’s hand to

…I am floundering and tossed about in torrents of iniquity.

But I take refuge in You,

Reach out Your hand to me as You did to Peter.

I.2

Ո՛վ խորք մեծութեան եւ իմաստութեան,

փրկեա՛ զըմբռնեալս՝

որ ի խորս մեղաց ծովուն անկեալ եմ.

- խորք, խրոց pit, depth, bottom, abyss

- փրկեմ, -եցի to save, deliver

- ըմբռնեմ, -եցի to seize, trap, catch

- մեղ, -աց sin

- ծով, -ուց sea

O depths of majesty and of wisdom,

Deliver me for I am trapped,

and I have fallen into the depths of the sea of sin.

I.7

նաւապետ բարի Յիսուս՝ փրկեա՛ զիս

ի բազմութենէ ալեաց մեղաց իմոց,

եւ տո՛ւր ինձ նաւահանգիստ խաղաղութեան։

- նաւապետ captain

- ալիք, ալեաց wave, surge, swell

- տո՛ւր impv 2sg տամ, ետու to give, provide, make

- նաւահանգիստ port, haven, harbor

- խաղաղութիւն peace, tranquility, rest, quiet

O Good Jesus, my Captain, save me

from the abundant waves of my sins,

and settle me in a peaceful harbor.

I.20

Ձգեա՛ Տէր՝զձեռս քո ի նաւաբեկեալս՝

որ ընկղմեալս եմ ի խորս չարեաց,

եւ փրկեա՛ զիս ի սաստիկ ծովածուփ բռնութենէ ալեաց մեղաց իմոց։

- ձգեմ, -եցի to stretch, extend, draw

- նաւաբեկիմ to run aground, founder, be shipwrecked

- ընկղմեմ, -եցի to sink, submerge, drown, bury

- շարիք, -րեաց, -րեօք evil deeds, iniquity; disaster

- սաստիկ, սաստկաց extreme, intense, violent, strong

- ծովածուփ tempestuous, stormy

- բռնութիւն violence, fury (< բուռն, բռանց fist, with many other derivatives)

Stretch forth, O Lord, Your hand to me for I am shipwrecked

and I am drowning in the abyss of my evil deeds.

Deliver [me] from the stormy and violent force of the waves of my sins.

I.64

Խաղաղացո՛ զիս Տէր՝ ի ծփանաց ալեաց խռովութեանց խորհրդոց,

եւ զբազմւոթեան յորձանս մեղաց իմոց ցածո՛,

եւ կառավարեա՛ զմիտս իմ ժամանել

յանքոյթ եւ ի խաղաղ նաւահանգիստն Հոգւոյդ սրբոյ։

- Խաղաղացո՛ impv 2sg խաղաղացուցանեմ, խաղաղացուցի to calm

- ծփանք wave, billow

- ձորձան, -աց current, torrent, whirlpool

- ցածո՛ impv 2sg ցածուցանեմ, ցածուցի to reduce, diminish, soften, calm, humiliate

- կառավերեմ, -եցի to guide, direct, govern

- միտ, մտի, զմտաւ, միտք, մտաց, մտօք mind, understanding

- ժամանեմ, -եցի to arrive, be able, happen

- անքոյթ safe, secure

Grant me peace, O Lord, from the billowy waves of my turbulent thoughts,

Abate the many whirlpools of my sins.

Steer my mind that it may come

To the safe and peaceful harbor of Your Holy Spirit.

In I.81, we have, not the sea, but, it seems, a river (something fordable):

Անցո՛ զիս Տէր՝ ընդ հուն անցից մեղաց…

- Անցո՛ impv 2sg անցուցանեմ, անցուցի to cause to pass, carry back, transmit

- հուն, հնի ford, shallow passage

- անցք, անցից passage, street, channel, opening

Bring me, O Lord, through the ford of the river of sins…

The sea and drowning are by no means the only metaphors for sin in these prayers. Others from pt. I include ice (15), dryness (21), thorn (23; also p. 120, line 8), sleep (25), darkness (39, 102), nakedness (44-45), bondage and prison (54, 93), a quagmire (62), an abyss (71), “dung and slime” (72), and a weight and burden (123, 125, 129). From pt. III, p. 106, ll. 29-30:

հա՜ն զիս ի տղմոյ անօրէնութեան իմոյ,

զի մի՛ ընկլայց յաւիտեան։

- հա՜ն impv 2sg հանեմ, հանի to remove, dislodge, lift up

- տիղմ, տղմոյ mire, mud, filth

- ընկլայց aor subj m/p 1sg ընկլնում, -կլայ (also ընկղմիմ, -եցայ!) to founder, sink, be plunged

- յաւիտեան, -ենից eternity

Remove me from the mire of my iniquity

lest I sink in forever.

Metaphors from nature for things other than sin are “the ice of disobedience,” “the fog of mistrust,” “the raging torrents of desires for pleasures,” and ” the spring of falsehood” in pt. VI, p. 136, ll. 23-26.

Whether these places are of interest to you spiritually, conceptually, philologically, or some combination of those possibilities, I leave you to ponder them.

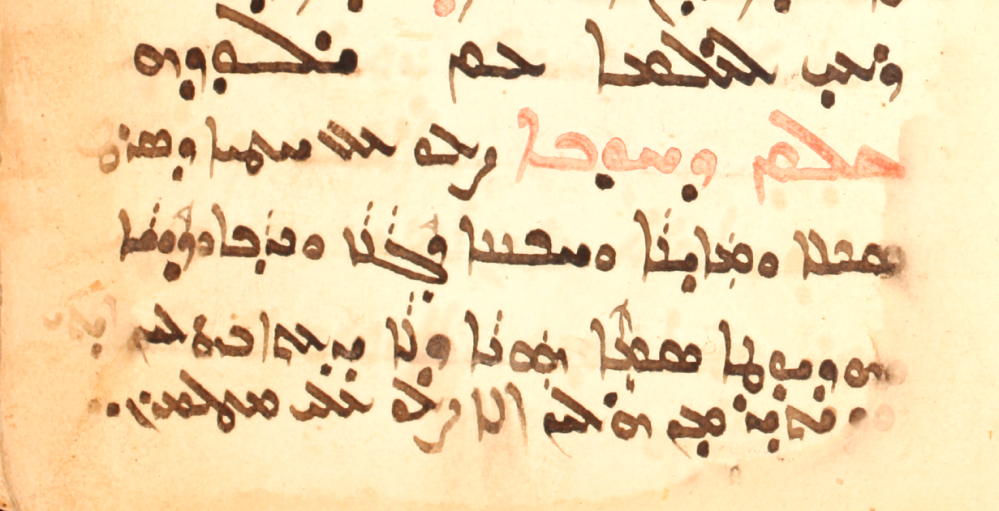

Saint Mark’s Monastery, Jerusalem, № 169 mostly contains homilies in Garšūnī, but at the beginning (ff. 4v-8r) there is an excerpt, in Syriac, from the Chronicle of Michael the Great, book 11 of chapter 20, on the Council of Manazkert (or Manzikert; see here for other forms of the name) convened in 726 by Catholicos Yovhannēs Ōjnec’i the Philosopher with Syriac Orthodox Patriarch Athanasios III. The title is “On the Unity Effected by Patriarch Athanasios and Catholicos John of the Armenians against the Heresy of Maximos that has Spread Abroad, and the Negation of the Phrase ‘Who was crucified for us.'” Neither Michael nor the title Chronicle are specifically mentioned here, however. This manuscript was copied outside of Amid/Diyarbakır; the date in the colophon seems to be 1092 AG, which is certainly wrong and probably a mistake for 2092 AG, so May 1781.

SMMJ 169, f. 4v

My friend and colleague, Ed Mathews, in his Armenian Commentary on Genesis attributed to Ephrem the Syrian, CSCO 573, (Louvain, 1998), pp. xlvii-xlviii, briefly discusses this council as follows:

It is fairly well known that a council of Manazkert, referred to by a number of historians, was convened in 726, by the great Armenian Kat‘ołikos Yovhannēs Ōjnec‘i, also known as the Philosopher (Arm., իմաստասէր) in order to quiet this dispute and come to some sort of union with the Syrian Church. This council was attended by a number of Armenian bishops and six Syrian bishops to try to effect a union between the two churches, and particularly, to find some common ground whereby each might suppress the more radical branch of Monophysitism as practiced by followers of Julian of Halicarnassus, who maintained the incorruptibility of the body of Christ. The Armenian historians, Step‘annos Asołik, Samuēl Anec‘i, Step‘annos Ōrbelian, and Kirakos Ganiakec‘i do little more than mention the council at all and, like the other historians just mentioned, seems far more interested in the personal appearance of Ōjnec‘i, being enthralled with his elaborate garments and even more with his gold-speckled beard. Clearly then, this council left no real lasting impression in the Armenian church.

As for Syriac sources on this council, as Mathews points out, Barhebraeus’ subsequent account (Chron. Eccl. 1.299-304) is based on that in Michael’s Chronicle, and there is also Dionysius b. Ṣalibi’s Against the Armenians. The bishop of Ḥarrān, Symeon of the Olives, associated with the Monastery of Mor Gabriel, attended the Council (cf. Brock “Fenqitho of the Monastery of Mor Gabriel in Tur ‘Abdin,” Ostkirchliche Studien 28 (1979): 168-182, here 177).

On the name of the place itself, Մանազկերտ, see Hübschmann, Die altarmenische Ortsnamen, 328, 330, 449-450, and Toumanoff, Studies in Christian Caucasian History, p. 218, n. 253, who points to the name of the Urartian king Menua as the source of the place-name. We may also note the important battle fought there in 1071, with the Byzantine army defeated by the Seljuks.

The name of the later fourth-century author and bishop Nemesius of Emesa may not often pass the lips even of those closely interested in late antique theology and philosophy, but his work On the Nature of Man (Περὶ φύσεως ἀνθρώπου, CPG II 3550), to judge by the evident translations of the work, attracted translators and readers in various languages. What follows are merely a few pointers to these translations and some related evidence in Greek, Armenian, Syriac, Georgian, and Latin (bibliography below), with renderings of the book’s incipit in the versions.

For Arabic, I don’t have any texts ready to hand, but with attribution to Gregory of Nyssa, Isḥāq b. Ḥunayn (d. 910/911) translated it into Arabic (GCAL I 319, II 130), and Abū ‘l-Fatḥ ʕabdallāh b. al-Faḍl (11th cent.) apparently writes in connection to the work in chs. 51-70 of his Kitāb al-manfaʕa al-kabīr (GCAL II 59). (Note also the latter’s translation and commentary to Basil’s Hexaemeron and its continuation by Gregory of Nyssa [GCAL II 56].)

Greek

Morani, Moreno, ed. Nemesii Emeseni De natura hominis. Bibliotheca scriptorum Graecorum et Romanorum Teubneriana. Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, 1987.

Older ed. in PG 40 504-817.

(ed. Morani, as quoted in Zonta, 231):

Τὸν ἄνθρωπον ἐκ ψυχῆς νοερᾶς καὶ σώματος ἄριστα κατεσκευασμένον

Armenian

See Thomson, Bibliography of Classical Armenian, 40. The Venice, 1889 ed. is available here.

title: Յաղագս բնութեան մարդոյ

Զմարգն ի հոգւոյ իմանալւոյ եւ ի մարմնոյ գեղեցիկ կազմեալ

- մարդ, -ոց man, mortal, human being

- իմանալի intelligible, perceptible; intelligent

- մարմին, -մնոց body

- գեղեցիկ, -ցկի, -ցկաց handsome, agreeable, proper, elegant, good

- կազնեմ, -եցի to form, model, construct, arrange

Latin

C. Burkhard, ed. Nemesii Episcopi Premnon Physicon sive Περὶ φύσεως ἀνθρώπου Liber a N. Alfano Archiepiscopo Salerni in Latinum Translatus. Leipzig: Teubner, 1917. At archive.org here.

It was translated into Latin by Alfanus of Salerno (fl. 1058-1085), and in the Latin tradition it is known by the Greek title πρέμνον φυσικῶν, “the trunk of physical things”. This seems to be the usual title (spelled variously in Latin letters, of course), and a marginal note has “Nemesius episcopus graece fecit librum quem vocavit prennon phisicon id est stipes naturalium. hunc transtulit N. Alfanus archiepiscopus Salerni.” The text begins thus:

A multis et prudentibus viris confirmatum est hominem ex anima intellegibili et corpore tam bene compositum…

Georgian

Gorgadze. S. ნემესიოს ემესელი, ბუნებისათჳს კაცისა (იოანე პეტრიწის თარგმანი). Tbilisi, 1914. The text from this edition is at TITUS here.

The translation is that of the famous philosopher and translator Ioane Petrici (d. 1125; Tarchnishvili, Geschichte, 211-225).

კაცისა სულისა-გან გონიერისა და სხეულისა რჩეულად შემზადებაჲ

- გონიერი wise, understanding

- სხეული body

- რჩეული choice, select

- შემზადებაჲ preparation

Syriac

The witness to a Syriac translation is fragmentary. It has been studied by Zonta. The incipit of Nemesius’ work appears in two places, and differently.

1. from Timotheos I (d. 823), Letter 43, as given in Pognon, xvii:

ܥܩܒ ܬܘܒ ܘܥܠ ܣܝܡܐ ܕܐܢܫ ܦܝܠܣܘܦܐ ܕܡܬܩܪܐ ܢܡܘܣܝܘܣ ܕܥܠ ܬܘܩܢܗ ܕܒܪܢܫܐ ܘܐܝܬܘܗܝ ܪܫܗ ܗܢܐ. ܒܪܢܫܐ ܡܢ ܢܦܫܐ ܡܬܝܕܥܢܝܬܐ ܘܦܓܪܐ ܛܒ ܫܦܝܪ ܡܬܩܢ

Brock’s ET (“Two Letters,” 237): “Search out for a work by a certain philosopher called Nemesius, on the structure of man, which begins: ‘Man is excellently constructed as a rational soul and body…’”

2. from Iwannis of Dara (fl. first half of 9th cent.), De anima, in Vat. Syr. 147, as given by Zonta, 231:

ܒܪܢܫܐ ܡܢ ܢܦܫܐ ܝܕܘܥܬܢܝܬܐ ܘܦܓܪܐ ܡܪܟܒ

Bibliography

(In addition to the already cited editions, etc.)

Brock, Sebastian P., ”Two Letters of the Patriarch Timothy from the Late Eighth Century on Translations from Greek”, Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 9 (1999): 233-246.

Motta, Beatrice, ”Nemesius of Emesa”, Pages 509-518 in The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity. Edited by Gerson, Lloyd Phillip. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Pognon, Henri. Une version syriaque des aphorismes d’Hippocrate. Texte et traduction. Pt. 1, Texte syriaque. Leipzig, 1903.

Sharples, Robert W. and van der Eijk, Philip J., Nemesius. On the Nature of Man. Translated Texts for Historians 49. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008.

Zonta, Mauro, ”Nemesiana Syriaca: New Fragments from the Missing Syriac Version of the De Natura Hominis”, Journal of Semitic Studies 36:2 (1991): 223-258.

Lately I have been cataloging a group of manuscripts from Saint Mark’s Monastery, Jerusalem, that have homiletic contents, especially the mēmrē of Jacob of Serug, including some that are hitherto unpublished. One of these manuscripts is SMMJ 162, from the late 19th or early 20th century. I don’t mention it here so much for the texts the scribe penned into it, but rather for a little colophon left at the end of Jacob’s Mēmrā on Love (cf. Bedjan, vol. 1, 606-627), f. 181r:

SMMJ 162, f. 181r

Pray for the sinner who has written [it], a fool, lazy, slothful, deceitful, a liar, wretched, stupid, blind of understanding, with no knowledge of these things, [nor] more than these things, but pray for me for our Lord’s sake!

Almost from the beginning of my time cataloging at HMML, I have been collecting excerpts of scribal notes and colophons that I found interesting for some reason or other, one such reason being the extreme self-loathing and self-deprecation that scribes not uncommonly trumpet. The cases in which scribes go on and on with adjectives or substantives of negative sentiment can elicit almost a humorous reaction, but scribes who do this do give their readers some semantically related vocabulary examples all in one spot!

NB: If interested, see my short article in Illuminations, Spring 2012, pp. 4-6, available here, for a popular presentation on colophons.

The Dormition of Mary is celebrated August 15 (for those that follow the old calendar = Aug 28 in the Gregorian calendar), so today is an opportune time to study a few lines on the Dormition from the Georgian version of Maximus the Confessor‘s Life of the Virgin, which survives only in that language.

The Georgian text was edited (and translated into French) by Michel-Jean van Esbroeck, Maxime le confesseur. Vie de la Vierge, CSCO 478/Scr. Iber. 21 (Louvain, 1986). Here is the text from § 103, pp. 133.25-134.14:

ოდეს იგი იგულებოდა ქრისტესა ღმერთსა ჩუენსა ამიერ სოფლით განყვანებად ყოვლად წმიდისა მის და უბიწოჲსა დედისა თჳსისა, და სასუფეველად ზეცისა მიყვანებად რაჲთა სათნოებათა და ბუნებისა უვაღრესთა მოღუაწებათა მისთა გჳრგჳნი საუკუნაჲ მიიღოს, და ფესუედითა ოქროანითა პირად-პირადად შემკობილი შუენიერად დადგეს მარჯუენით მისა, და დედუფლად იქადაგოს ყოველთა დაბადებულთა, და შევიდეს შინაგან კრეტსაბმელისა და წმიდასა წმიდათასა დაემკჳდროს. წინაჲთვე გამოუცხადა დიდებული იგი მიცვალებაჲ მისი. და მოუვლინა მას კუალად მთავარანგელოსი გაბრიელ მახარებელად დიდებულისა მის მიცვალებისა მისისა, ვითარცა იგი პირველ საკჳრველისა მის მუცლადღებისა. მოვიდა უკუჱ მთავარანგელოსი და მოართუა რტოჲ ფინიკისაჲ რომელი იგი იყო სასწაული ძლევისაჲ, ვითარცა ოდესმე ძესა მისსა მიეგებვოდეს რტოებითა ფინიკისაჲთა მძლესა მას სიკუდილისასა და შემმუსრველსა ჯოჯოხეთისასა, ეგრეთვე წმიდასა მას დედუფალსა მოართუა მთავარანგელოსმან რტოჲ იგი სახე ძლევისა ვნებათაჲსა და სიკუდილისა გან უშიშობისა.

We are fortunate to have an English translation of this text, only recently published (2012), by Stephen Shoemaker, The Life of the Virgin: Maximus the Confessor. Here is his rendering of the passage given above (p. 130):

When Christ our God wanted to bring his all-holy and immaculate mother forth from the world and lead her into the kingdom of heaven so that she would receive the eternal crown of virtues and supernatural labors, and so that he could place her at his right hand beautifully adorned with golden tassels in many colors (cf. Ps 44:10, 14) and proclaim her queen of all creatures, and so that she would pass behind the veil and dwell in the Holy of Holies, he revealed her glorious Dormition to her in advance. And he sent the archangel Gabriel to her again to announce her glorious Dormition, as he had before the wondrous conception. Thus the archangel came and brought her a branch from a date palm, which is a sign of victory: as once they went with branches of date palms to meet her son (cf. John 12:13), the victor over death and vanquisher of Hell, so the archangel brought the branch to the holy queen, a sign of victory over suffering and fearlessness before death.

Turning back to the Georgian text, the structure of this little excerpt falls along these lines. There are four sentences, beginning with, respectively,

- ოდეს იგი იგულებოდა…

- და მოუვლინა მას…

- მოვიდა უკუჱ…

- ვითარცა ოდესმე…

The main clause of sent. 1 comes at its end, წინაჲთვე გამოუცხადა დიდებული იგი მიცვალებაჲ მისი, the temporal setting for which comes at the beginning, ოდეს იგი იგულებოდა ქრისტესა ღმერთსა ჩუენსა…. Precisely what he wishes (იგულებოდა) to do in this temporal setting is given immediately thereafter by means of two verbal nouns in the adverbial case (განყვანებად and მიყვანებად), the object of both being Jesus’ mother, only explicitly said in the first instance, and in the genitive case according to the normal construction with a verbal noun. These two verbal nouns have for their purpose (or result) five clauses following რაჲთა built with a string of aorist conjunctive verbs with either Mary or Jesus as subject.

The other sentences are much simpler. Sent. 2’s main clause is მოუვლინა მას კუალად მთავარანგელოსი გაბრიელ, with the archangel being sent as a messenger or announcer (მახარებელად). This clause is correlated with the next one, ვითარცა იგი პირველ საკჳრველისა მის მუცლადღებისა, for which the same participle in the adverbial case is again understood. What I am calling sent. 3 is two compound clauses, მოვიდა უკუჱ მთავარანგელოსი and მოართუა რტოჲ ფინიკისაჲ, this last word being extended by a relative clause to state what the branch (რტოჲ) is a sign (სასწაული) of. The last sentence again has two main clauses, this time correlated by ვითარცა and ეგრეთვე. The first of these clauses has a verb with an unnamed plural agent (მიეგებვოდეს), the indirect object of which, ძესა მისსა, is extended by two appositive noun phrases, მძლესა მას სიკუდილისასა and შემმუსრველსა ჯოჯოხეთისასა, both in the dative case in agreement with the noun they further identify, while the second clause has a singular verb, მოართუა, already seen in this passage, the agent being the archangel Gabriel. In the last clause of the passage, the direct object რტოჲ იგი — in the nominative case as direct object of an aorist verb — is followed by the appositive სახე, itself extended by two genitive noun phrases (ძლევისა ვნებათაჲსა and სიკუდილისა გან უშიშობისა).

(A PDF document including most of the material from this post along with some further grammatical details is available: maxim_conf_dormition.)

Today (Aug 19) some churches celebrate the Transfiguration, and there are readings for the feast in published synaxaria in Arabic, Armenian, and Gǝʿǝz. A close reading and comparison of the language of these texts would be worthwhile, but now I’d like only to share part of the Gǝʿǝz reading, namely the three sälam verses that close the commemoration of the Transfiguration. (On the genre of the sälam, see this post.) Most typically, there is only one five-line verse in the Gǝʿǝz synaxarion at the end of the commemoration of a saint or holy event, but for this important feast there are three together, the verses ending, respectively, with the syllabic rhymes -ʿa/ʾa, -wä, -se. As usual, verses like this provide a good learning opportunity for students interested in Gǝʿǝz, both in terms of lexicon and grammar, the latter especially thanks to the freer arrangement of the sentence’s constituents that obtains in this kind of writing.

I give Guidi and Grébaut’s text from PO 9: 513-514, together with a new, rough English translation.

ሰላም፡ለታቦር፡እንተ፡ተሰምየ፡ወተጸውዓ።

ደብረ፡ጥሉለ፡ወደበረ፡ርጉዓ።

ባርቅ፡ሞአ፡በህየ፡ወኃይለ፡ሲሳራ፡ተሞአ።

ወቦቱ፡አሪጎ፡አመ፡ኢየሱስ፡ተሰብአ።

ምሥጢረ፡ምጽአቱ፡ዳግም፡ከሠተ፡ኅቡአ።

ሰላም፡ለዕርገትከ፡ዓቀበ፡ደብረ፡ታቦር፡ጽምወ።

እምብዙኃን፡ነሢአከ፡እለ፡ኃረይከ፡ዕደወ።

ኢየሱስ፡ዘኮንከ፡እምቤተ፡ይሁድ፡ሥግወ።

ርእየተ፡ገጽከ፡አምሳለ፡መብረቅ፡ሐተወ።

ወከመ፡በረድ፡ልብሰከ፡ፃዕደወ።

ፀርሐ፡አብ፡ኪያከ፡በውዳሴ።

ወርእስከ፡ጸለለ፡ምንፈሰ፡ቅዳሴ።

አመ፡ገበርከ፡በታቦር፡ምስለ፡ሐዋርያት፡ክናሴ።

ኤልያስ፡መንገለ፡ቆመ፡ወኀበ፡ሀለወ፡ሙሴ።[1]

ዘመለኮትከ፡ወልድ፡ከሠትከ፡ሥላሴ።

Greetings to Tabor, which is named and called

The fertile mountain and the firm mountain!

There Barak conquered, and the might of Sisera was conquered.

And having ascended [that mountain], when Jesus had become man,

He revealed the hidden mystery of his second coming.

Greetings to your ascent up the slope of Mount Tabor in tranquility!

Having taken the men you had chosen from among many,

Jesus, you who were incarnate from the house of Judah,

The appearance of your face shined like lightning,

And your clothes were as white as snow.

The Father proclaimed you in praise,

And the Spirit of holiness concealed your head.

When you had made an assembly of apostles,

Where Elijah was present and where Moses was,

You, Son, showed the trinity of your divinity.

Note

[1] The two prepositions in this line behave more like adverbs than prepositions, given that a relative pronoun pointing back to ክናሴ፡ in the previous line is omitted: “assembly at [which] Elijah was present and with [which] Moses was.” Cf. Dillmann, Gr., § 201.

Jn 16:33, Pre-Athonite and Athonite:

მე მიძლევიეს სოფელსა.

ἐγὼ νενίκηκα τὸν κόσμον.

The Adishi version, instead of the perfect (a-me-victum-est = vici), has the aorist ვსძლე.

The saint known as Marina (Margaret in the west) — not to be confused with Marina the Monk — is in some churches celebrated on July 30. In the synaxaria available to me, I find her story only in the Gǝʿǝz for Hamle 23 (see PO 7:386-389, with a sälam). Her tale, quite fantastic, is known in many languages. Here is an outline of the version of the aforementioned Gǝʿǝz synaxarion, with some excerpts in that language.

Her father, Decius (ዳኬዎስ፡), was a chief of the idol-priests (ሊቀ፡ገነውተ፡አማልክት፡ዘሀገረ፡አንጾኪያ፡), and with the saint’s mother dead, he gave her over to the care of a nurse or guardian (ሐፃኒት፡), who was a Christian and who taught her the faith (ወመሐረታ፡ሃይማኖተ፡ክርስቶስ፡). One day, inspired by hearing about the martyrs (ሰምዓት፡እንዘ፡ትትናገር፡ሐፃኒታ፡ጻማ፡ተጋድሎቶሙ፡ለሰማዕታት፡), the young saint, then around fifteen years old, went out to seek martyrdom herself (ሖረት፡እንዘ፡ተኃሥሥ፡ከዊነ፡ስምዕ፡). On meeting a “wicked magistrate” (፩መኰንን፡ዓላዊ፡), who characteristically inquires as to her identity, she equally characteristically responds, “I am of the people of Jesus Christ, and my name is Marina” (አነ፡እምሰብአ፡ኢየሱስ፡ክርስቶስ፡ወስምየ፡መሪና፡). The magistrate noticed Marina’s beauty and splendor (ስና፡ወላሕያ፡) and could not control himself (ስእነ፡ተዓግሦ፡), so he tried to persuade her with all kinds of talk to make her agree to give herself to him (ወሄጣ፡ብኵሉ፡ነገር፡ከመ፡ኦሆ፡ትብሎ፡), but she would not, of course, and instead she cursed him and slandered his gods (ረገመቶ፡ወፀረፈት፡አማልክቲሁ፡). This results in the magistrate’s command that she be beaten with iron bars, cut and lacerated (አዘዘ፡ይቅሥፍዋ፡በአብትረ፡ሐፂን፡ወይምትሩ፡መለያልዪሃ፡ወይሥትሩ፡ሥጋሃ፡) “until her blood flowed like water” (እስከ፡ውኅዘ፡ደማ፡ከመ፡ማይ፡). The saint prays and Michael the archangel heals her (ፈወሳ፡), but she is then thrown into prison, an especially dark one (ቤተ፡ሞቅሕ፡ዘምሉእ፡ጽልመት፡). There she again prays, Michael comes and illumines the prison, and he takes her to heaven and before returning her he shows her the habitation of the saints and the just (ወአዕረጋ፡ውስተ፡ሰማይ፡ወአርአያ፡ማኅደረ፡ቅዱሳን፡ወጻድቃን፡). Once, while she is praying, having endured more tortures and having received subsequent archangelic healing, a huge serpent (or dragon) comes to her “from one of the corners of the prison” (መጽአ፡ኀቤሃ፡እማእዘንተ፡ቤተ፡ሞቅሕ፡ዐቢይ፡ተመን፡). She is afraid of it, and it swallows her whole as she has her arms extended in prayer in the shape of a cross (ወውኅጣ፡እንዘ፡ስፉሕ፡እደዊሃ፡በአምሳለ፡መስቀል፡ወትጼሊ፡በልባ፡)! Just then, the serpent’s belly splits open, and the saint emerges unharmed (ተሠጥቀ፡ከርሡ፡ወወፅአት፡እምኔሁ፡ዘእንበለ፡ሙስና፡)! On her way back through the prison in another direction, she sees Satan sitting down in the form of a black man (በአምሳለ፡ብእሲ፡ጸሊም፡), his hands gripping the top of his knees (ወጽቡጣት፡እደዊሂ፡ዲበ፡አብራኪሁ፡); she marks him with the sign of the cross, grabs him by the hair and beats him with some kind of scourge (አኃዘቶ፡በሥዕርተ፡ርእሱ፡ወዘበጠቶ፡በበትረ፡መቅሠፍት፡)! After that, in a vision of the cross with a talking white dove on it (ተከሥተ፡ላቲ፡ዕፀ፡መስቀሉ፡ለኢየሱስ፡ክርስቶስ፨ወዲቤሁ፡ትነብር፡ርግብ፡ፀዓዳ፡), she knows her time of departure is near. The next day, the magistrate orders her stripped (አዘዘ፡መኰንን፡ያዕርቅዋ፡ልብሰ፡), hung upside down (ወይስቅልዋ፡ቍልቍሊተ፡), burned (ወያውዕይዋ፡በእሳት፡), and thrown into a cauldron of boiling liquid (ወይደይዋ፡ውስተ፡ጽሕርት፡ዘቦቱ፡ማይ፡ፍሉሕ፡). As she is praying inside the cauldron, a dove with a golden crown in its mouth comes and frees her bonds and baptizes her in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and the saint emerges from the liquid. The magistrate has had enough and orders her decapitated (ወአዘዘ፡ከመ፡ይምትሩ፡ርእሳ፡በሰይፍ፡), but before she dies, Jesus comes to her and promises (ወወሃባ፡ኪዳነ፡) that her name and story will have an especially effective intercessory power.

So much for the tale of Saint Marina/Margaret. This fabulous (in the original sense of the word) story offers readers quite a spectacle of hagiography. We have several martyrological topoi, and students of Gǝʿǝz will find the excerpts, if not the whole, worth their time to pore over.

Today (July 22) in some churches the feast of Mary Magdalene is celebrated. How about a few lines on her from the Ethiopian synaxarion, where she is commemorated on the 28th of Ḥamle (Aug 4)? These lines belong to the genre of the sälam (greeting; usually called ʿarke when outside of the synaxarion), five rhyming lines — e.g. the lines below all end in -ma — that typically conclude a saint’s mention in the Ethiopian synaxarion. The synaxarion in Gǝʿǝz goes back to the Arabic synaxarion for the Coptic church compiled by Michael of Atrīb and Malīg in the 13th century. The earliest Gǝʿǝz recension, from the end of the 14th century, survives in only three manuscripts, one of which being EMML 6458, for the first half of the year; another early, but distinct, witness is EMML 6952. In the sixteenth century, following a notable rise of interest in local hagiography, the synaxarion was revised, first, it seems, at Däbrä Ḥayq Ǝsṭifanos, but with a rival recension also from Däbrä Libanos. It is this sixteenth century revision, known as the Vulgate recension, that has the sälam verses. This corpus, a unique contribution of Gǝʿǝz hagiography, offers students of hagiography and students of the Gǝʿǝz language a long list of reading material sure to hold their attention. Here is the one for Mary Magdalene, the text in PO 7 435, and my translation.

ሰላም፡ለመግደላዊት፡ማርያም፡ስማ።

ትንሣኤ፡ክርስቶስ፡ዘርእየት፡እምሐዋርያት፡ቀዲማ።

ለአንስት፡ሰላም፡ዘተሳተፋ፡ድካማ።

እንዘ፡ይትራወጻ፡ኀበ፡መቃብሩ፡ለጠቢብ፡ፌማ።

እንበለ፡ያፍርሆን፡ምንተ፡ዘሌሊት፡ግርማ።

Greetings to the Magdalene, Mary by name,

Who saw Christ’s resurrection first among the apostles.

Greetings to the women who shared in her toil

As they ran together to the tomb of the Wise Craftsman

Without the terror of the night frightening them.

Bibliography (further bibliography in each of these articles)

Aßfalg, Julius. “Synaxar(ion).” In H. Kaufhold, ed., Kleines Lexikon des christlichen Orients. 2d ed. Wiesbaden, 2007. Pp. 448-449.

Colin, Gérard and Alessandro Bausi. “Sǝnkǝssar.” Encyclopaedia Aethiopica IV 621-623.

Nosnitsin, Denis. “Sälam.” Encyclopaedia Aethiopica IV 484.

Yalew, Samuel. “ʿArke.” Encyclopaedia Aethiopica I 342.

Pilate’s famous question to Jesus in John 18:38, which reads the same in the Adishi, Pre-Athonite, Athonite versions (on the Old Georgian Gospels, and the rest of the New Testament, see the recent survey by Childers in the bibliography below):

ჰრქუა მას პილატე: რაჲ არს ჭეშმარიტებაჲ?

λέγει αὐτῷ ὁ Πιλᾶτος· τί ἐστιν ἀλήθεια;

Pilate said to him, “What is truth?”

The last word of the line is derived from the adjective ჭეშმარიტი, itself from Armenian ճշմարիտ, on which see Ačaṛyan’s dictionary, vol. 3, p. 209, available online here. Other examples of this and related words are easy to find: John 1:9 (Adishi) იყო ნათელი ჭეშმარიტი Ἦν τὸ φῶς τὸ ἀληθινόν; 1:14 სავსჱ მადლითა და ჭეშმარიტებითა πλήρης χάριτος καὶ ἀληθείας; and from the K᾽art᾽lis c᾽xovreba, არა იყო წინასწარმეტყუელი და მოძღუარი სჯულისა ჭეშმარიტისა “there was no prophet and teacher of the true faith” (Rapp, Qauxch᾽ishvili, and Abuladze, eds., K᾽art᾽lis c᾽xovreba: The Georgian Royal Annals and Their Medieval Armenian Adaptation, 2 vols. Delmar, NY: Caravan Books, 1998, vol. 1, p. 18).

Jacek Malczewski, Christ before Pilate, 1910. See here.

Bibliography

Childers, Jeff W. 2012. “The Georgian Version of the New Testament.” In The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis, edited by Bart D. Ehrman and Michael W. Holmes, 2nd ed., 293–327. New Testament Tools, Studies and Documents 42. Brill.