Archive for the ‘Medicine’ Category

Readers of this blog are undoubtedly aware of the recent reports of the destruction of the Monastery of Mar Behnam and Sara (see here, here, and elsewhere). The fate of the monastery’s manuscripts is now unknown. Not long ago, at least, HMML and the CNMO (Centre numérique des manuscrits orientaux) digitized the collection. A short-form catalog of these 500+ manuscripts has been prepared for HMML by Joshua Falconer, and I have taken a more detailed look at a select number of manuscripts in the collection. From this latter group I would like to highlight a few and share them with you. The texts mentioned below are biblical, hagiographic, apocryphal/parabiblical, historical, poetic, theological, medical, lexicographic, and grammatical. Here I merely give a few rough notes, nothing comprehensive, along with some images, but in any case the value and variety of these endangered manuscripts will, I hope, be obvious.

These manuscripts, together with those of the whole collection, are available for viewing and study through HMML (details for access online and otherwise here).

MBM 1

Syriac Pentateuch. Pages of old endpapers in Syriac, Garšūnī, and Arabic. Very many marginal comments deserving of further study to see how they fit within Syriac exegetical tradition. The comments are anchored to specific words in the text by signs such as +, x, ~, ÷. According to the original foliation, the first 31 folios are missing.

- Gen 1r-58v (beg miss; starts at 20:10)

- Ex 59r-129v

- Lev 129v-180v

- Num 181r-241r

- Deut 241r-283v (end miss; ends at 28:44)

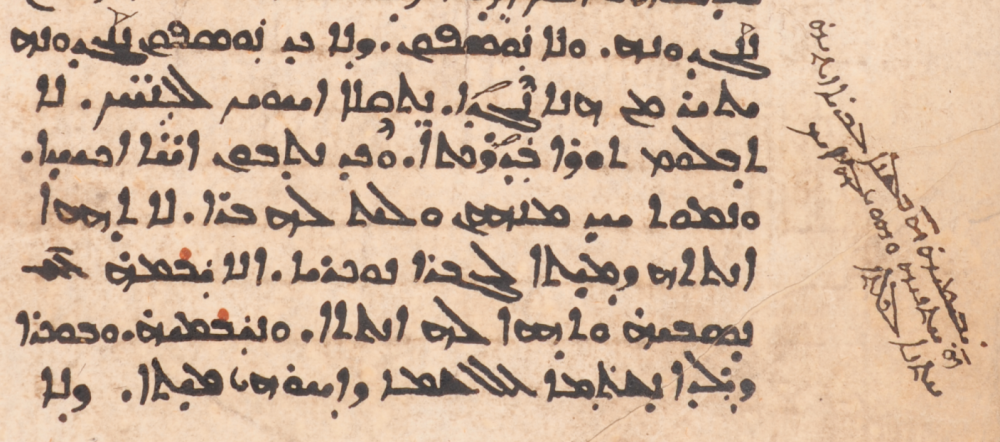

MBM 1, f. 105v, with marginal note to Ex 28:37, with the Greek letter form of the tetragrammaton.

MBM 1, f. 275v, with marginal note on Dt 25:5 explaining ybm as a Hebrew word.

MBM 20

Syriac texts on Mary and the young Jesus. Folio(s) missing, and the remaining text is somewhat disheveled. In addition, some pages are worn or otherwise damaged. Colophon on 79v, but incomplete.

- The Book of the Upbringing of Jesus, i.e. the Syriac Infancy Gospel, 1r-12v. Beg. miss. See the published text of Wright, Contributions to the Apocryphal Literature of the New Testament, pp. 11-16 (Syr), available here.

- The Six Books Dormition 13r-79r (beg and end miss?). See Wright, “The Departure of my Lady from this World,” Journal of Sacred Literature and Biblical Record 6 (1865): 417–48; 7: 110–60. (See also his Contributions to the Apocryphal Literature) and Agnes Smith Lewis, Apocrypha Syriaca, pp. 22-115 (Syr), 12-69 (ET); Arabic version, with LT,by Maximilian Enger, Ioannis Apostoli de transitu beatae Mariae Virginis liber (Elberfeld, 1854) available here. In this copy, the end of the second book is marked at 24v, and that of the fifth book on 30v. As indicated above, there are apparently some missing folios and disarranged text.

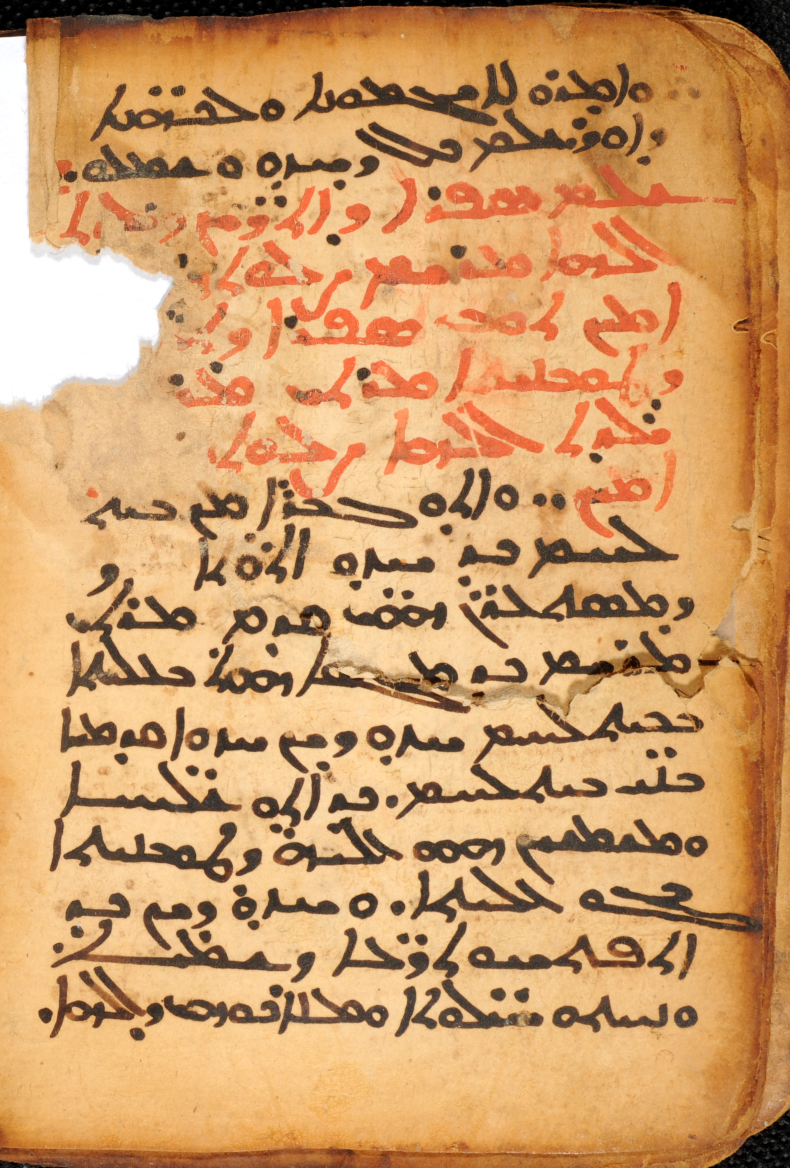

MBM 20, f. 24v. End of bk 2, start of bk 3 of the Six Books.

MBM 120

Another copy of Eliya of Nisibis, Book of the Translator, on which see my article in JSS 58 (2013): 297-322 (available here).

MBM 141

Bar ʿEbrāyā’s Metrical Grammar. Colophon on 99r: copied in the monastery of Symeon the Stylite, Nisan (April) 22, at the ninth hour in the evening of Mar Gewargis in the year 1901 AG = 1590 CE.

MBM 144

Bar ʿEbrāyā’s Metrical Grammar, d. 1492/3 on 78v. Clear script, but not very pretty.

MBM 146

Bar ʿEbrāyā, Book of Rays. Lots of marginalia in Syriac, Arabic, and Garšūnī.

MBM 152

Bar Bahlul’s Lexicon, 18th cent. Beg. miss. Some folios numbered by original scribe in the outer margin with Syriac letters, often decorated. Nice writing. Beautiful marbled endpapers, impressed Syriac title on spine.

MBM 152, spine.

MBM 152, marbled endpapers.

MBM 172

The Six Books Dormition, Garšūnī, from books 5-6, 16th cent. (?).

MBM 207

Hagiography, &c., Garšūnī, 16th/17th cent. According to the original foliation, the first eleven folios are missing from the manuscript.

- 1r end of the Protoevangelium Jacobi (for the corresponding Syriac part, cf. pp. 21-22 in Smith Lewis’s ed. here). Here called “The Second Book, the Birth”.

- 1r-31v Vision of Theophilus, here called “The Third Book, on the Flight to Egypt…” Cf. GCAL I 229-232; Syriac and Arabic in M. Guidi, in Rendiconti della Accademia dei Lincei, Classe di scienze morali, storiche e filologiche, 26 (1917): 381-469 (here); Syriac, with ET, here.

- 31v-37v book 6, The Funeral Service (taǧnīz) of Mary

- 37v-39r Another ending, from another copy, of this book 6

- 39r-62r Miracle of Mary in the City of Euphemia

- 62r-72v Marina and Eugenius

- 72v-96r Behnam & Sara (new scribe at ff 83-84)

- 96r-104r Mart Shmoni and sons

- 104r-112v Euphemia (another scribe 112-114)

- 112v-124v Archellides

- 124v-131r Alexis, Man of God, son of Euphemianus

- 131v-141v John of the Golden Gospel

- 141v-147v Eugenia, Daughter of the King/Emperor (incom)

MBM 209

19th cent., Garšūnī, hagiography. Not very pretty writing, but includes some notable texts (not a complete list): Job the Righteous 3v, Jonah 14v, Story of the Three Friends 24r (?), Joseph 73r, Ahiqar 154v, Solomon 180v, and at the end, another Sindbad text 197v-end (see the previous posts here and here).

MBM 209, f. 197v. The Story of Hindbād and Sindbād the Sailor.

MBM 250

Medical, very nice ES Garšūnī. Includes Ḥunayn’s Arabic translation of the Summary of Galen’s On the Kinds of Urine (fī aṣnāf al-bawl), ff. 1v-8r; cf. here. For a longer Greek text, see Kuehn, Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia (Leipzig, 1821-33), vol. 19, pp. 574-601. These now separate folios seem originally to have been the eighth quire of another codex.

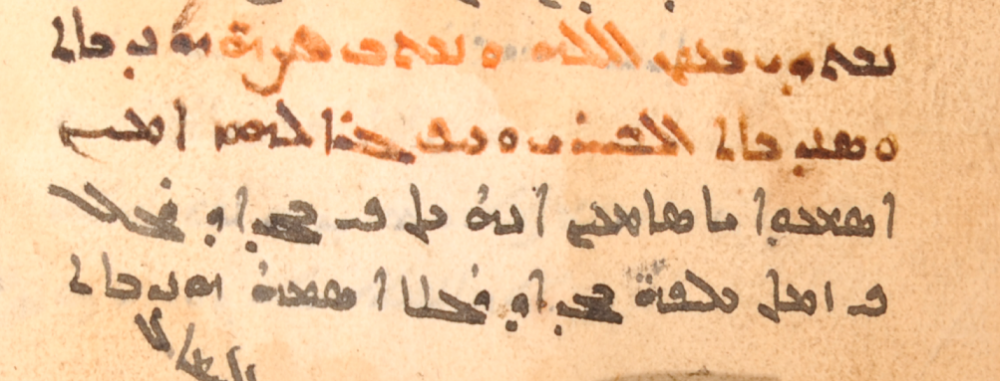

MBM 250, f. 1v. Beg. of Ḥunayn’s Arabic translation of the Summary of Galen’s On the Kinds of Urine.

MBM 270

John of Damascus, De fide Orthodoxa, Arabic (cf. Graf, GCAL II, p. 57, this ms not listed). Fine writing. 16th/17th cent.

MBM 270, f. 5v. John of Damascus, Arabic.

MBM 342

A late copy (19th cent.), but with a fine hand, of the Kitāb fiqh al-luġa, by Abū Manṣūr ʿAbd al-Malik b. Muḥammad al-Ṯaʿālibī, a classified dictionary: e.g. § 17 animals (82), § 23 clothing (155), § 24 food (173), § 28 plants (205), § 29 Arabic and Persian (207, fīmā yaǧrá maǧrá al-muwāzana bayna al-ʿarabīya wa-‘l-fārisīya).

MBM 364

Syriac, 15th cent. (?). F. 10v has quire marker for end of № 11. The manuscript has several notes in different hands:

- 29v, a note with the year 1542 (AG? = 1230/1 CE); Ascension and Easter are mentioned

- 31v, note: “I had a spiritual brother named Ṣlibā MDYYʾ. He gave me this book.” (cf. 90v)

- 66v, note: “Whoever reads this book, let him pray for Gerwargis and ʿIšoʿ, the insignificant monks.”

- 90v, note: Ownership-note and prayer-request for, it seems, the monk Ṣlibonā (cf. 31v)

- 132v, longish note similar to the note on 168v

- 157r, note: “Theodore. Please pray, for the Lord’s sake.”

- 168v, note: “I found this spiritual book among the books of the church of the Theotokos that is in Beth Kudida [see PS 1691], and I did not know [whether] it belonged to the church or not.”

For at least some of the contents, cf. the Syriac Palladius, as indicated below.

- Mamllā of Mark the Solitary, Admonition on the Spiritual Law 1r-17r

Second memra 17r

Third memra 41v

Fourth memra 48r

- Letters of Ammonius 67r-78v (see here; cf. with Kmosko in PO 10 and further CPG 2380)

- “From the Teaching of Evagrius” 78v-100r

- Confession of Evagrius 100v

- Abraham of Nathpar 101r-117v

2nd memra 105r

3rd memra 109v

4th memra 110v

5th memra 115v

- Teachings of Abba Macarius 117v

- Letter (apparently of Macarius) 130r-130v

- Letter of Basil to Gregory his Brother 131r-139v

- Letter from a solitary to the brothers 139v-142r

- Sayings of Evagrius 142r-146v

- Gluttony 147v

- The Vice of Whoring (ʿal ḥaššā d-zānyutā) 147v

- Greed 148r

- Anger 149r

- Grief 149v

- On the Interruption of Thought (ʿal quṭṭāʿ reʿyānā) 149v

- Pride 150r

- From the Tradition (mašlmānutā) of Evagrius 151r

- On the Blessed Capiton (here spelled qypyṭn) 151r (cf. Budge, Book of Paradise, vol. 2, Syr. text, p. 223)

- The Blessed Eustathius 151v

- Mark the Mourner 151v

- A student of a great elder in Scetis 152r

- A student of another elder who sat alone in his cell 155v

- A student of a desert elder 156r

- (more short saint texts) 157v-161r

- Tahsia 161r-164r (cf. Budge, Book of Paradise, vol. 2, Syr. text, p. 173)

- An Elder named Zakarya 164r

- Gregory 168r

- Daniel of Ṣalaḥ 180v

- Philemon 180v (cf. Budge, Book of Paradise, vol. 2, Syr. text, p. 427)

- One of the Blessed Brothers 181r

- Pachomius, with various subtexts and miracles 182v

- Didymus 188v-190v

MBM 365

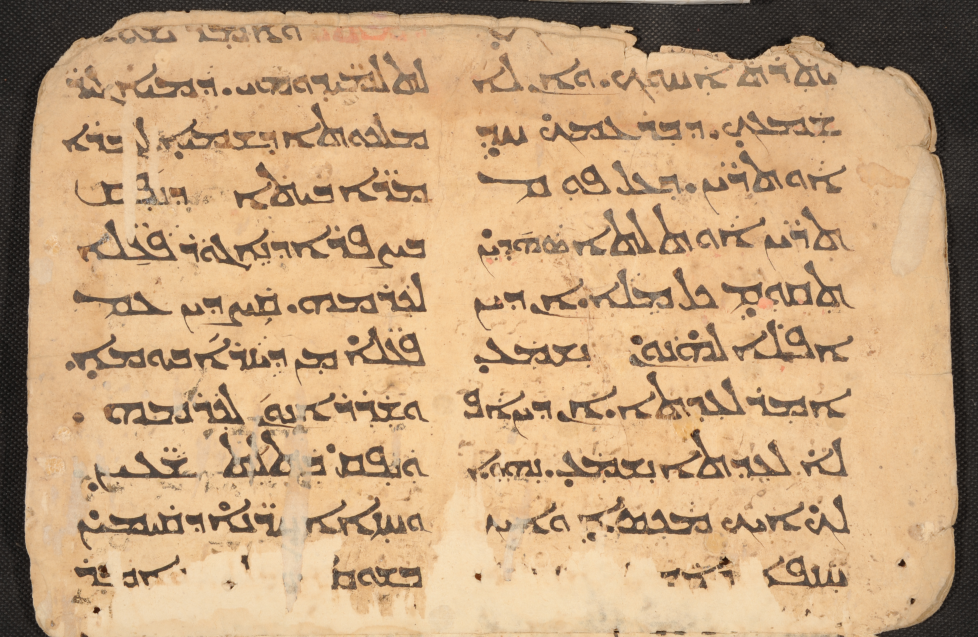

Arabic, 15th century (?). Second, but probably contemporaneous with the first, scribe begins at 80r.

- 1r-34r Pss 38:17-150 (end)

- 34r-79v maqāla 11 by Saint Simʿān, maqāla 12 by Simʿān, … maqāla 16 by Simʿān on 67r. There is some apparent disarray and missing folios: the end of this group of texts seems really to be 78v, but 79r has “Sayings and Questions of Abū ‘l-qiddīs Simʿān”

- 80r-114r Jn 7:20-21:25 (i.e. end of the Gospel)

MBM 365, f. 79r, the beginning of the Saying and Questions of Saint Simʿān

MBM 367

Two loose folios of an Arabic tafsīr of the Gospels, one of which has the quire marker for the original thirty-first quire (so numbered with Syriac letters). Perhaps 16th cent. From Mt 10, with commentary (qāla ‘l-mufassir), on 1v (image below); Lk 6:20 ff. on f. 2r.

MBM 367, f. 1v. Mt 10:19-23 with the beginning of the commentary.

MBM 368

Garšūnī (very nice, clear script). Memre and other texts on theological, monastic, and spiritual subjects.

MBM 386

17th cent., Garšūnī, hagiography. Note the Qartmin trilogy beginning on 105v.

- The Book of the Ten Viziers / Arabic version of the Persian Baḫtīār Nāma 1r (beg miss). (On this work, see W.L. Hanaway, Jr., in EIr here.) It is a frame story spread over several days with a boy (ġulām) telling smaller stories (sg. ḥadīṯ) to a king. As it now stands in the manuscript, it begins in the eighth day, ending on the eleventh. (ET of the Persian here by William Ouseley; ET by John Payne of an Arabic version with Alf layla wa-layla here, eighth day beg. on p. 125). Here are the subdivisions:

The Story of [the city of] Īlān Šāh and Abū Tamām 1v

Ninth day 7r

King Ibrāhīm and his son (on 9r, marginalia in Arabic: “this is an impossible thing!”)

Tenth day 14r

Story of Sulaymān 15v

Eleventh day, 29v

- Infancy Gospel of Jesus 33v-55r

- John of Dailam 55r-68v

- Behnām and Sara 68v-73v

- Mar Zakkay 73v-105r (at 105r it says Mar Malke)

- Mar Gabriel 105v-132r (much of f. 111 torn away; partly f. 127, too)

- Mar Samuel 132v- (folios miss. after ff. 141, 157)

- Mar Symeon -163v (begins where?)

- Memra of Ephrem on Andrew when he entered the land of the dogs 163v

- Miracle of Mary 170v

- Miracle of Mark of Jabal Tarmaq 172v

MBM 388

17th cent., ES Garšūnī, mostly hagiography. Colophon on 135v.

- Story of Susanna

- Ephrem on Elijah 14r

- Story of a Jewish Boy and what happened to him with some Christian children 31v (hands change at 34r)

- Story of some royal children 40v (some Syriac, hands change at 47r)

- Story of Tatos the martyr (f.), martyred in Rome 51r

- Story of a Mistreated Monk 58v

- Story of Arsānīs, King of Egypt 66v

- John of the Golden Gospel 70v (folio(s) missing after 70v)

- Elijah the Zealous 88v

- Andrew the Apostle 100v

- Text by Eliya Catholicos, Patriarch 111r

- Zosimus and the Story of the Rechabites 116r

- Story of the Apple 131r (several other copies at HMML: CFMM 350, pp. 717-722; CFMM 109, ff. 179v-182r; CFMM 110, 182v-185v; ZFRN 73, pp. 382-390 and more)

MBM 390

17th cent., WS Garšūnī, some folios missing, hagiographic, homiletic, &c.

- Ahiqar 1r (on 27r dated 2006 AG in Arabic script)

- Merchant of Tagrit and his Believing Wife 27v

- Chrysostom, On Receiving the Divine Mysteries 34r

- Chrysostom, On Repentance and Receiving the Divine Mysteries 44v (s.t. miss. after 51v)

- Ephrem, (beg. miss.) 52r ? (s.t. miss. after 67v)

- Jacob of Serug, On Repentance 69v (s.t. miss after 69v)

- Ephrem ? 94r

- From the Fathers, That everyone has a guardian angel 102v (hands change just b/f this)

- Story of Petra of Africa 110r (no other Arabic/Garšūnī at HMML; for Syriac, see CFMM 270, pp. 291-302)

- Zosimus and the Story of the Rechabites, 119v-132r

- Life of John the Baptist 132r

- Five Miracles of John the Baptist 150r

- Story of Macarius (end miss) 152v-153v

MBM 469

Ecclesiasticus, Garšūnī, with some Turkish-Arabic/Garsh equivalents at beginning.

MBM 469, f. 1v. Turkish words with Arabic/Garšūnī equivalents.

Here are the forms on this page, first in Turkish, then Arabic:

- ıslattı naqaʿa [he soaked]

- aramış fattaša [he searched]

- aradın fattašta [you searched]

- aradım fattaštu [I searched]

- aramışlar fattašū [they searched]

- işitti samiʿa [he heard]

- içti šariba [he drank] *The Turkish root here is written with š for ç, as in Kazakh; on the previous page the verb also appears and is spelled ʾyǧty, i.e. içti (Garšūnī ǧīm = Turkish c or ç.)

Note that for the forms of aramak [to search], the third person forms are past indefinite, while the first and second person forms are past definite.

MBM 485

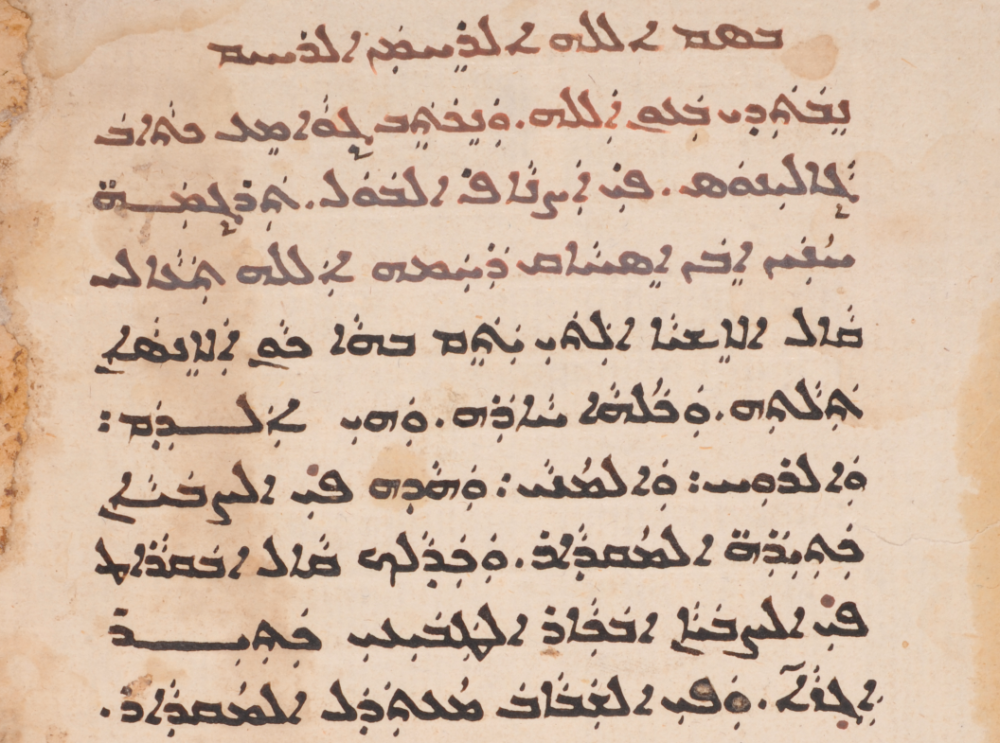

From a Gospel lectionary, Syriac, Estrangela. Here is f. 6v, with Mt 18:15-17, 20:1-3.

MBM 485, f. 6v. Mt 18:15-17, 20:1-3.

MBM 489

French drama translated into Syriac by Abraham ʿIso in Baghdad, 1972-1974.

- [5r] title page

- [6r-7v] introduction

- pp. 5-122 Athalie by Racine

- pp. 125-244 Le Cid by Corneille

- pp. 247-380 Polyeucte by Corneille

- pp. 381-463 Esther by Racine

MBM 489, f. 74r = p. 125. Title page to the Syriac translation of Corneille’s Le Cid.

With the first page of the Syriac Le Cid cf. the original text here. Note that the Syriac translation is in rhyming couplets like the French.

MBM 489, f. 77r = p. 131. The beginning of the Syriac Le Cid.

MBM 509

19th cent., Arabic. ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Baġdādī. Starts with excerpt from Ibn Abī Uṣaybiʿa on him (cf. the end of the ms). On 14r begins the K. al-Ifāda wa-‘l-iʿtibār fī ‘l-umūr wa-‘l-mušāhada wa-‘l-ḥawādiṯ al-muʿāyana bi-arḍ Miṣr. See De Sacy’s annotated FT here.

Here is the part from ch. 4, on monuments (beg. 30r), about the burning of the library of Alexandria by ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ “with the permission of ʿUmar” and on the Pharos of Alex (bottom of 34v = de Sacy p. 183).

MBM 509, f. 34v.

MBM 514

Printed work. Mariano Ugolini. Vasco de Gama al Cabo das Tormentas, dodecasillabi siriaci con versione italiana. Rome, Tipografia Poliglotta, 1898. “Poesia letta in Roma nella solenne accademia per le feste centenarie della scoperta delle Indie, il giorno 21 Maggio 1898.” 6 pages. Bound with Rahmani’s Testamentum Domini.

Here are the first six lines:

MBM 514, p. 4.

And the same in Italian:

MBM 514, p. 5.

Since this blog’s inception there has been in the list of links one to digital editions of ZDMG, etc. In the same collection there are now 196 title of the series Islamkundliche Untersuchungen (h/t Sabine Schmidtke), a series covering a range of studies historical, literary, textual, linguistic, and social in the Middle East, and despite its title, the series is not strictly confined to Islamica. Every reader will have his or her own favorites or titles of interest, but as a sampling of the long list of books from this series freely available, here are a few of my own, with direct links:

Galen: “Über die Anatomie der Nerven” : Originalschrift und alexandrinisches Kompendium in arabischer Überlieferung / Ahmad M. Al-Dubayan

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/256824

The stories of the Prophets by Ibn Muṭarrif al-Ṭarafī / ed. with an introd. and notes by Roberto Tottoli

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/280877

Studien zum ältesten alchemistischen Schrifttum : auf der Grundlage zweier erstmals edierter arabischer Hermetica / Ingolf Vereno

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/297787

Die Kritik der Prosa bei den Arabern : (vom 3./9. Jahrhundert bis zum Ende des 5./11. Jahrhunderts) / Mahmoud Darabseh

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/304891

Über die Steine : das 14. Kapitel aus dem “Kitāb al-Muršid” des Muḥammad Ibn Aḥmad at-Tamīmī, nach dem Pariser Manuskript herausgegeben, übersetzt und kommentiert / Jutta Schönfeld

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/1071856

Die Entstehung und Entwicklung der osmanisch-türkischen Paläographie und Diplomatik : mit einer Bibliographie / Valery Stojanow

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/846828

Ibn ar-Rāhibs Leben und Werk : ein koptisch-arabischer Enzyklopädist des 7./13. Jahrhunderts / Adel Y. Sidarus

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/847474

Der Orientalist Johann Gottfried Wetzstein als preussischer Konsul in Damaskus (1849 – 1861) : dargestellt nach seinen hinterlassenen Papieren / Ingeborg Huhn

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/344941

Das Verhältnis von Poesie und Prosa in der arabischen Literaturtheorie des Mittelalters / Ziyad al-Ramadan az-Zuʿbī

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/518946

Mädchennamen – verrätselt : 100 Rätsel-Epigramme aus d. adab-Werk Alf ǧāriya wa-ǧāriya (7./13. Jh.) / Jürgen W. Weil

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/309887

Der arabische Dialekt von Mekka : Abriß der Grammatik mit Texten und Glossar / Giselher Schreiber

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/305137

Das Kitāb ar-rauḍ al-ʿāṭir des Ibn-Aiyūb : Damaszener Biographien des 10./16. Jahrhunderts, Beschreibung und Edition / Ahmet Halil Güneş

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/301056

Studien zur Grammatik des Osmanisch-Türkischen : unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Vulgärosmanisch-Türkischen / von Erich Prokosch

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/304595

Arabic literary works as a source of documentation for technical terms of the material culture / Dionisius A. Agius

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/275281

Kritische Untersuchungen zum Diwan des Kumait b. Zaid / Kathrin Müller

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/238296

Athanasius von Qūṣ Qilādat at-taḥrīr fī ʿilm at-tafsīr : eine koptische Grammatik in arabischer Sprache aus dem 13./14. Jh. / von Gertrud Bauer

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/176618

Erziehung und Bildung im Schahname von Firdousi : eine Studie zur Geschichte der Erziehung im alten Iran / von Dariusch Bayat-Sarmadi

http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/ssg/content/titleinfo/176609

Happy reading.

Last year about this time I participated in the North American Syriac Symposium at Duke University, and next week will take place on Malta the eleventh quadrennial international Symposium Syriacum and the ninth Conference on Christian Arabic Studies. I’ll be presenting a paper there on Job of Edessa’s Treatise on Rabies, and in another session I’ll participate in a presentation to give an update on some of HMML’s recent activities in the fields of Syriac and Arabic manuscripts. For anyone who cares, here’s the abstract for the paper on Job of Edessa’s work on rabies:

Last year about this time I participated in the North American Syriac Symposium at Duke University, and next week will take place on Malta the eleventh quadrennial international Symposium Syriacum and the ninth Conference on Christian Arabic Studies. I’ll be presenting a paper there on Job of Edessa’s Treatise on Rabies, and in another session I’ll participate in a presentation to give an update on some of HMML’s recent activities in the fields of Syriac and Arabic manuscripts. For anyone who cares, here’s the abstract for the paper on Job of Edessa’s work on rabies:

While the history and sources of the science of human medicine in Arabic and (to a lesser extent) Syriac literature have attracted a reasonable amount of scholarly attention, the same cannot be said for veterinary medicine, almost certainly due to the latter field’s greater paucity of sources. One such source, however — all the more important because there are not many of them — has been known in the west for almost a century now but has never been studied: a Syriac text entitled A Treatise on Rabies by Job (Iyob or Ayyūb) of Edessa (d. ca. 835). This work, which also deals with serpents and scorpions in addition to rabid canines, survives, as far as is known, in three late manuscripts, and it has never been edited or translated. Where the author is known, it is for his much longer and encyclopedic Book of Treasures (ed. and tr. 1935), the only other work of Job’s that survives, though a few other theological, medical, and philosophical titles are known. Both Job and his son Ibrāhīm served as physicians in the Abbasid entourage, and Job is mentioned in Arabic sources, including Ḥunayn b. Isḥāq’s Risālah, as a prolific translator of Galen’s works into Syriac. The work on rabies, an original composition divided into eight sections, deals with, among other things, the propensity of dogs to this affliction, the fear of water experienced by rabid dogs and people with rabies, a comparison of rabies with other animal stings and poisons, and the lethality of a rabid dog’s bite. The object of this paper is to make this interesting and thus far unstudied text better known. After some details on the life and work of Job of Edessa and on the history of veterinary medicine, especially in the Middle East, the subject turns to Job’s text itself by analyzing its contents, outlining the scientific vocabulary, investigating the author’s possible sources, and situating it within the history of science and veterinary medicine.

I’m looking forward to talking with colleagues and friends in Syriac and Arabic studies, and, of course, to seeing Malta, whither I’ve never been.

P.S. The title of this post was chosen with a full nod to Lead Belly’s “Alabama Bound” (my home state)!

Saint Mark’s Monastery, Jerusalem, 235 is a thick tome containing Dāʾūd Al-Anṭākī’s (d. 1599) Taḏkirat ulī ‘l-albāb wa-‘l-ǧāmiʿ li-‘l-ʿaǧab al-ʿuǧāb (The Reminder for Those with Understanding, and the Collector of Prodigious Wonders), a lengthy and thorough medical work divided into four sections with an introduction and epilogue, in Garšūnī; there are a number of manuscripts of the work known, but as far as I am aware, other than this copy they are all in Arabic script. This Jerusalem manuscript is dated 1757 AD and 1171 AH. In the margin of the next-to-last page someone has written (in Arabic script, unlike the text in the manuscript itself) the following:

SMMJ 235, f. 491v

English’d:

Property of the monastery of the Syrians in honorable Jerusalem. Anyone who steals or removes [it] from its place of donation will be cursed from the mouth of God! God (may he be exalted) will be angry with him! Amen.

This curse against would-be book robbers is hardly unique in Arabic — I have seen a number in the collections at HMML in both Arabic and Garšūnī — and similar warnings are well known in other traditions, too. From Paris Gr 301, for example, Elpidio Mioni (Introduzione alla paleografia greca [Padua, 1973], 85) cites Εἴ τις δὲ βουληθῇ ἆραι τοῦτον κρυφίως ἢ καὶ φανερῶς, ἔχῃ τὰς ἀρὰς τῶν ιβʹ ἀποστόλων καὶ κατάραν εὕρῃ κακίστην πάντων μοναχῶν, “Should anyone wish to take this [book] secretly, or even openly, he will get the curses of the twelve apostles and find the worst anathema of all the monks!” Interested readers will find a wealth of (mostly Latin) examples in Marc Drogin’s delightful work Anathema! Medieval Scribes and the History of Book Curses (Totowa and Montclair, New Jersey, 1983).

Any other such gems, in any language, you’re aware of?

Note

On Dāʾūd Al-Anṭākī see GAL II 364 and GALS II 491-492. Wüstenfeld (Gesch. der Arabischen Aerzte [Göttingen, 1840], 158) calls the Taḏkirat “ein grosses Werk über die gesammte theoretische und practische Medicin” and Leclerc (Hist. de la médecine arabe, vol. 2 [Paris, 1876], 304) says it “embrasse la majeure partie de la science”. Much more recent, there is an entry on Dāʾūd by Raphaela Veit in the Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3d ed. (available online by subscription), with bibliography.

Siddhartha Mukherjeeh’s Emperor of Maladies: A Biography of Cancer (New York, 2010), a 500-plus page popular level survey of cancer in human history, with the bulk of the period covered being the last hundred years or so, thanks especially to the substantial advancements achieved in that time, has received wide acclaim. One service the work performs is that it informs a general readership that cancer is nothing new. I’d like to point here to a recent identification of a short passage on cancer in an Arabic (Garšūnī) manuscript from Mardin, but before I do that, it will be worthwhile to highlight, without going into any great detail, some resources in Greek and Arabic that touch on cancer. (Jacob Wolff — see the full reference below — at the beginning of the 20th century traced the history of the disease; I’ll not be surprised if there’s something comparable that is more recent, but I don’t know it offhand.)

The Ebers papyrus, in (hieratic) Egyptian, dated to the 16th century BCE, refers to a kind of tumor thought to have been cancer, but it’s not until much later that we get a name for cancer that sticks. Hippocrates (c. 450-c. 380 BCE) is given credit for naming the disease “crab” (καρκίνος = Latin cancer, Syriac sarṭānā, Arabic saraṭān). (Incidentally, this is one of many cases where English medical convention has opted for Greek or Latin words taken over wholesale instead of translations of those terms; German, by contrast, has Krebs.) A few centuries later, Galen (130-200 CE), too, discusses cancer (and other tumors). The Galenic emphasis and contribution for cancer is that it is caused by black bile. Some centuries after Galen, we have a focused description of cancer by Paul of Aegina (7th cent. CE) in his Medical Epitome (cf. also the passage on cancers in the womb from Ibn Sarābiyūn based on Paul in P. Pormann, Paul of Aegina, 27-28). I have collected a number of other notable passages, but I refer to just a few here. Photios in the 9th century had the following to say of cancer in his Lexicon (κ p. 132), “καρκίνος is a sensation [or “misfortune”] occurring in bodies, which is now called καρκίνωμα; it is often found.” The Suda s.v. is similar, as also Hesychios, Lex. κ no. 832; see Paul of Aegina, Epit. 6.45 for a longer description, and Oribasios, Coll. Med. 45.11.4.1, quoting Xenophon (medicus), for some different types of cancer occurring in different parts of the body. The term καρκίνωμα is defined in the Definitiones medicae wrongly attributed to Galen (Kühn, vol. 19, 430.6 and 443.5). Again in another work of a pseudo-Galen we see that καρκινώματα are especially common in female breasts (Introductio, Kühn, vol. 14, 779.8-9, cf. 786.8; see also Hipp. Epid. 5.1.101).

As is well known, Syriac scholars spent considerable efforts poring over and translating Greek scientific works, and in the ninth century some of them — Ḥunayn b. Isḥāq is the most famous — played the unimaginably important role of further translating some of such texts into Arabic, sometimes from Syriac, sometimes directly from Greek. There are in Ḥunayn b. Isḥāq’s Risāla on the translations of Galen’s works into Syriac and Arabic (ed. Bergsträsser, 1925) three references of possible relevance: on Galen’s Ad Glauconem de medendi methodo libri II, De tumoribus praeter naturam, and De atra bile. The Risāla, a new edition of which with English translation by John Lamoreaux is thankfully soon to appear, is a well-known resource for our knowledge of Greek medical literature in both Syriac and Arabic. This work is well known as a resource for the history of Arabic medical literature, but it bears underlining that many of the translations Ḥunayn refers to are Syriac; even if these are not all known to have survived, it is at least a boon to our Syriac literary knowledge to know that such and such a Galenic text did exist in that language. In the second book of Ad Glauconem, Ḥunayn tells us (p. 7, ll. 10-11), Galen “describes the indicators of tumors and their treatments” (ويصف في المقالة الثانية دلائل الاورام ومداواتها); this term (waram pl. awrām) does not, however, necessarily mean a cancerous tumor. This work had been translated into Syriac by Sergius of Rēšʿainā († 536) — at a time, Ḥunayn says, when he was somewhat accomplished in translation but he was not yet at the peak of his skill — before Ḥunayn himself translated it into Syriac and then into Arabic for different patrons (p. 7, ll. 12-16: وقد كان سبقني الى ترحمة هذا الكتاب سرجس الى السريانيّة وقد كان قوويّ بعض القوّة في الترجمة ولم يبلغ غياته ثم ترجمته بعد الى السريانيّة لسلمويه…ثمّ ترجمته في هذا الايام الى العربيّة لابي جعفر محمّد بن موسى). The other two books (nos. 57 and 68 in the Risāla), which I do not quote here due to space, are discussed on p. 31.4-9, and p. 32.14-16. The medical bio-bibliographer Ibn Abī Uṣaybiʿa hardly mentions cancer: the only place I know of is at the end of ch. 8 (p. 255 in the Beirut ed. before me) for a physician called Al-Sāhir (“the sleepless”), also known as Yūsuf the Priest, and even there the reference to the disease is somewhat tangential:

وقال عبيد الله بن جبرائيل عنه إنّه كان به سرطان في مقدم رأسه وكان يمنعه من النوم فلقب بالساهر من اجل مرضه قال وصنف كناشا يذكر فيه ادوية الامراض وذكر في كناشه اشياء تدلّ على أنّه كان به هذا المرض

ʿUbayd Allāh b. Jibrāʾīl said of him that he had cancer on his forehead and that it would prevent him from sleeping, and so he was nicknamed Al-Sāhir because of his disease. He also said that he had put together a compendium [kunnāš] in which he mentions the remedies of diseases, and he mentioned in his book certain things indicating that he did in fact have this disease.

Finally, the main cause inciting me to pen this post: I have recently discovered two copies — Church of the Forty Martyrs, Mardin, 555(2) and 556, the former very incomplete and less accurate in comparison with the latter—of a medical text in Garšūnī manuscripts, both undated but perhaps of the 16th or 17th century. This anonymous work consists of a catalog of illnesses with their descriptions and treatments. Each section generally consists of these four (rubricated) headings: al-maraḍ (the disease), al-sabab (its cause), al-ʿarḍ (its presentation, manifestation), al-tadbīr (its regulation, steps to be taken against it). At this point I have no further data to identify the text, whether for author, date, or possible other manuscripts, but I welcome any additional information. Here are just a few lines from this work on cancer. In this section — no. 56 in 556, but no. 55 in 555(2) — cancer is grouped with dubayla (a stomach disease) and kumna (black cataract), and the ailments are each discussed in turn.

With the parts on these other illnesses omitted, the text reads (ms. no. 556 with some variants from 555(2) in brackets):

Al-sabab. Wa-l-saraṭān ḫilṭ sawdāwī ḥādiṯ bi-l-qarnī [bi-l-qarānī, om. ḥādiṯ].

Al-ʿarḍ. Wa-ʿalāmat al-saraṭān ṣalābat al-ʿayn wa-tamaddud ʿurūqihā.

Al-tadbīr. Wa-ammā al-saraṭān lā burū lahu [lā budd wa-lahu] ġayr an al-ṭabīb yajtahidu fī taskīn alamihi wa-taḫfīf aḏīyatihi bi-stifrāġ al-badan wa-bi-l-aġdiya [om. wa-] al-muʿtadila wa-bi-an yaḍaʿa ʿalá l-ʿayn ṣufrat al-bayḍ maḍrūba maʿa kaṯīra wa-bi-laban al-nisā wa-bayāḍ al-bayḍ maʿa šay yasīr min [maʿa] iklīl al-malik fa-iḏā sakana al-wajaʿ fa-yajibu an yukḥala al-ʿayn bi-l-tūtiyā [om. -l-] wa-l-šādanaj [wa-l-sādanaj] wa-l-luʾluʾ wa-l-našā taduqq [yaduqq] al-adwiya wa-tanḫul [wa-yanḫul] wa-yattaḫiḏ kuḥlan wa-yaktaḥil bihi.

And here is an admittedly rough translation:

The cause: Cancer is black bile occurring on the side of the head.

Its manifestation: The mark of cancer is a hardening of the eye and the stretching out of its veins.

Its regulation: As for cancer, there is no recovery for it, even though the physician may make efforts to placate the patient’s suffering and to reduce his pain by evacuating the body, by balanced nutrition, or by putting the well-beaten yellow of an egg with women’s milk and egg-white with a little melilot on the eye. If the pain lessens, then it is necessary that zinc, lentil-stone, pearls, and starch be applied to the eye. Crush the medicinal ingredients and strain them; let the patient take it and apply it to his eye.

The remark, “there is no recovery for it,” a prognosis unfortunately still all too true for many, is reminiscent of other remarks about cancer in ancient and medieval medical literature. The command in the Egyptian Ebers papyrus has “do nothing against it”. More generally, Hippocrates in Aphorisms 7.87 counsels, “Diseases that medicines don’t heal, the knife heals; those that the knife doesn’t heal, fire heals; those that fire doesn’t heal we have to consider incurable” (Ὁκόσα φάρμακα οὐκ ἰῆται, σίδηρος ἰῆται· ὅσα σίδηρος οὐκ ἰῆται, πῦρ ἰῆται· ὅσα δὲ πῦρ οὐκ ἰῆται, ταῦτα χρὴ νομίζειν ἀνίατα), and in 6.38 (6.37 in the Syriac version) he recommends leaving “hidden cancers” (κρυπτοὶ καρκίνοι) untreated, since treating them will only cause a quick death, and presumably the cancer itself will still kill the patient, just not as quickly. See P. Pormann and E. Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine 130 for a similarly bleak prognosis from 14th-century Spain.

_______________________________

Suplementary note: I don’t know the source of the sentence, but H. Fähnrich (in his chapter in A. Harris, ed., Indigenous Languages of the Caucasus, vol. 1, p. 202) cites in Georgian the line ძუძუსა ჩემსა მჯდომი მაზის “a cancer is on my breast.”

_______________________________

Bibliography

Peter Pormann, The Oriental Tradition of Paul of Aegina’s Pragmateia (Leiden, 2004).

——– and Emilie Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine (Washington, D.C., 2007).

Jacob Wolff, Die Lehre von der Krebskrankheit. Four volumes. Gustav Fischer: Jena, 1907. In English see The Science of Cancerous Disease from Earliest Times to the Present, trans. Barbara Ayoub.

Readers of this blog are undoubtedly aware of the recent reports of the destruction of the Monastery of Mar Behnam and Sara (see here, here, and elsewhere). The fate of the monastery’s manuscripts is now unknown. Not long ago, at least, HMML and the CNMO (Centre numérique des manuscrits orientaux) digitized the collection. A short-form catalog of these 500+ manuscripts has been prepared for HMML by Joshua Falconer, and I have taken a more detailed look at a select number of manuscripts in the collection. From this latter group I would like to highlight a few and share them with you. The texts mentioned below are biblical, hagiographic, apocryphal/parabiblical, historical, poetic, theological, medical, lexicographic, and grammatical. Here I merely give a few rough notes, nothing comprehensive, along with some images, but in any case the value and variety of these endangered manuscripts will, I hope, be obvious.

These manuscripts, together with those of the whole collection, are available for viewing and study through HMML (details for access online and otherwise here).

MBM 1

Syriac Pentateuch. Pages of old endpapers in Syriac, Garšūnī, and Arabic. Very many marginal comments deserving of further study to see how they fit within Syriac exegetical tradition. The comments are anchored to specific words in the text by signs such as +, x, ~, ÷. According to the original foliation, the first 31 folios are missing.

MBM 1, f. 105v, with marginal note to Ex 28:37, with the Greek letter form of the tetragrammaton.

MBM 1, f. 275v, with marginal note on Dt 25:5 explaining ybm as a Hebrew word.

MBM 20

Syriac texts on Mary and the young Jesus. Folio(s) missing, and the remaining text is somewhat disheveled. In addition, some pages are worn or otherwise damaged. Colophon on 79v, but incomplete.

MBM 20, f. 24v. End of bk 2, start of bk 3 of the Six Books.

MBM 120

Another copy of Eliya of Nisibis, Book of the Translator, on which see my article in JSS 58 (2013): 297-322 (available here).

MBM 141

Bar ʿEbrāyā’s Metrical Grammar. Colophon on 99r: copied in the monastery of Symeon the Stylite, Nisan (April) 22, at the ninth hour in the evening of Mar Gewargis in the year 1901 AG = 1590 CE.

MBM 144

Bar ʿEbrāyā’s Metrical Grammar, d. 1492/3 on 78v. Clear script, but not very pretty.

MBM 146

Bar ʿEbrāyā, Book of Rays. Lots of marginalia in Syriac, Arabic, and Garšūnī.

MBM 152

Bar Bahlul’s Lexicon, 18th cent. Beg. miss. Some folios numbered by original scribe in the outer margin with Syriac letters, often decorated. Nice writing. Beautiful marbled endpapers, impressed Syriac title on spine.

MBM 152, spine.

MBM 152, marbled endpapers.

MBM 172

The Six Books Dormition, Garšūnī, from books 5-6, 16th cent. (?).

MBM 207

Hagiography, &c., Garšūnī, 16th/17th cent. According to the original foliation, the first eleven folios are missing from the manuscript.

MBM 209

19th cent., Garšūnī, hagiography. Not very pretty writing, but includes some notable texts (not a complete list): Job the Righteous 3v, Jonah 14v, Story of the Three Friends 24r (?), Joseph 73r, Ahiqar 154v, Solomon 180v, and at the end, another Sindbad text 197v-end (see the previous posts here and here).

MBM 209, f. 197v. The Story of Hindbād and Sindbād the Sailor.

MBM 250

Medical, very nice ES Garšūnī. Includes Ḥunayn’s Arabic translation of the Summary of Galen’s On the Kinds of Urine (fī aṣnāf al-bawl), ff. 1v-8r; cf. here. For a longer Greek text, see Kuehn, Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia (Leipzig, 1821-33), vol. 19, pp. 574-601. These now separate folios seem originally to have been the eighth quire of another codex.

MBM 250, f. 1v. Beg. of Ḥunayn’s Arabic translation of the Summary of Galen’s On the Kinds of Urine.

MBM 270

John of Damascus, De fide Orthodoxa, Arabic (cf. Graf, GCAL II, p. 57, this ms not listed). Fine writing. 16th/17th cent.

MBM 270, f. 5v. John of Damascus, Arabic.

MBM 342

A late copy (19th cent.), but with a fine hand, of the Kitāb fiqh al-luġa, by Abū Manṣūr ʿAbd al-Malik b. Muḥammad al-Ṯaʿālibī, a classified dictionary: e.g. § 17 animals (82), § 23 clothing (155), § 24 food (173), § 28 plants (205), § 29 Arabic and Persian (207, fīmā yaǧrá maǧrá al-muwāzana bayna al-ʿarabīya wa-‘l-fārisīya).

MBM 364

Syriac, 15th cent. (?). F. 10v has quire marker for end of № 11. The manuscript has several notes in different hands:

For at least some of the contents, cf. the Syriac Palladius, as indicated below.

Second memra 17r

Third memra 41v

Fourth memra 48r

2nd memra 105r

3rd memra 109v

4th memra 110v

5th memra 115v

MBM 365

Arabic, 15th century (?). Second, but probably contemporaneous with the first, scribe begins at 80r.

MBM 365, f. 79r, the beginning of the Saying and Questions of Saint Simʿān

MBM 367

Two loose folios of an Arabic tafsīr of the Gospels, one of which has the quire marker for the original thirty-first quire (so numbered with Syriac letters). Perhaps 16th cent. From Mt 10, with commentary (qāla ‘l-mufassir), on 1v (image below); Lk 6:20 ff. on f. 2r.

MBM 367, f. 1v. Mt 10:19-23 with the beginning of the commentary.

MBM 368

Garšūnī (very nice, clear script). Memre and other texts on theological, monastic, and spiritual subjects.

MBM 386

17th cent., Garšūnī, hagiography. Note the Qartmin trilogy beginning on 105v.

The Story of [the city of] Īlān Šāh and Abū Tamām 1v

Ninth day 7r

King Ibrāhīm and his son (on 9r, marginalia in Arabic: “this is an impossible thing!”)

Tenth day 14r

Story of Sulaymān 15v

Eleventh day, 29v

MBM 388

17th cent., ES Garšūnī, mostly hagiography. Colophon on 135v.

MBM 390

17th cent., WS Garšūnī, some folios missing, hagiographic, homiletic, &c.

MBM 469

Ecclesiasticus, Garšūnī, with some Turkish-Arabic/Garsh equivalents at beginning.

MBM 469, f. 1v. Turkish words with Arabic/Garšūnī equivalents.

Here are the forms on this page, first in Turkish, then Arabic:

Note that for the forms of aramak [to search], the third person forms are past indefinite, while the first and second person forms are past definite.

MBM 485

From a Gospel lectionary, Syriac, Estrangela. Here is f. 6v, with Mt 18:15-17, 20:1-3.

MBM 485, f. 6v. Mt 18:15-17, 20:1-3.

MBM 489

French drama translated into Syriac by Abraham ʿIso in Baghdad, 1972-1974.

MBM 489, f. 74r = p. 125. Title page to the Syriac translation of Corneille’s Le Cid.

With the first page of the Syriac Le Cid cf. the original text here. Note that the Syriac translation is in rhyming couplets like the French.

MBM 489, f. 77r = p. 131. The beginning of the Syriac Le Cid.

MBM 509

19th cent., Arabic. ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Baġdādī. Starts with excerpt from Ibn Abī Uṣaybiʿa on him (cf. the end of the ms). On 14r begins the K. al-Ifāda wa-‘l-iʿtibār fī ‘l-umūr wa-‘l-mušāhada wa-‘l-ḥawādiṯ al-muʿāyana bi-arḍ Miṣr. See De Sacy’s annotated FT here.

Here is the part from ch. 4, on monuments (beg. 30r), about the burning of the library of Alexandria by ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ “with the permission of ʿUmar” and on the Pharos of Alex (bottom of 34v = de Sacy p. 183).

MBM 509, f. 34v.

MBM 514

Printed work. Mariano Ugolini. Vasco de Gama al Cabo das Tormentas, dodecasillabi siriaci con versione italiana. Rome, Tipografia Poliglotta, 1898. “Poesia letta in Roma nella solenne accademia per le feste centenarie della scoperta delle Indie, il giorno 21 Maggio 1898.” 6 pages. Bound with Rahmani’s Testamentum Domini.

Here are the first six lines:

MBM 514, p. 4.

And the same in Italian:

MBM 514, p. 5.

Share this: