Archive for the ‘books’ Tag

I have spoken here before of my love of chrestomathies, with which especially earlier decades and centuries were perhaps fuller than more recent times. (I don’t know how old the word “chrestomathia” and its forms in different languages is, but the earliest use in English that the OED gives is only from 1832. We may note that, at least in English, the word has been extended to refer not only to books useful for learning another language, but simply to a collection of passages by a specific author, as in A Mencken Chrestomathy.) Chrestomathies may — and I really do not know — strike hardcore adherents to the latest and greatest advice of foreign language pedagogy as quaint and sorely outdated, my own view is that readers along these lines — text selections, vocabulary, more or less notes on points of grammar — can be of palpable value to students of less commonly taught languages, especially for those studying without regular recourse to a teacher. Since I’m talking about reading texts, I have in mind mainly written language and the preparation of students for reading, but that does not, of course, exclude speaking and hearing: those activities are just not the focus.

I have gone through seventy-one chrestomathies from the nineteenth to the twenty-first centuries in several languages (Arabic, Armenian, Coptic, Syriac, Georgian, Old Persian, Middle Persian, Old English, Middle English, Middle High German, Latin, Greek, Akkadian, Sumerian, Ugaritic, Aramaic dialects, &c.). The data (not absolutely complete) is available in this file: chrestomathy_data. By far the commonest arrangement is to have all the texts of the chrestomathy together, with or without grammatical or historical annotations, and then the glossary separately, and in alphabetical order, at the end of the book (or in another volume). Notable exceptions to this rule are some volumes in Brill’s old Semitic Study Series, Clyde Pharr’s Aeneid reader, and the JACT’s Greek Anthology, which contain a more or less comprehensive running vocabulary either on the page (the last two) or separately from the text (the Brill series). Some chrestomathies have no notes or vocabulary. These can be useful for languages that have hard-to-access texts editions or when the editor wants to include hitherto unpublished texts, but the addition of lexical and grammatical helps would even in those cases add definite value to the work for students.

In addition to these printed chrestomathies, there are some similar electronic publications, such as those at Early Indo-European Online from The University of Texas at Austin, which give a few reading texts for a number of IE languages: the texts are broken down into lines, each word is immediately glossed, and an ET is supplied, with a full separate glossary for each language.

From a Greek reader I have been putting together off and on.

Over the years, I have made chrestomathy texts in various languages, either for myself or for other students, and more are in the works. (Most are unpublished, but here is one for an Arabic text from a few years ago.) I have used different formats for text, notes, and vocabulary, and I’m still not decided on what the best arrangement is.

This little post is not a full disquisition on the subject of chrestomathies. I just want to pose a question about the vocabulary items supplied to a given text in a chrestomathy: should defined words be in the form of a running vocabulary, perhaps on the page facing the text or directly below the text, or should all of the vocabulary be gathered together at the end like a conventional glossary or lexicon? What do you think, dear and learned readers?

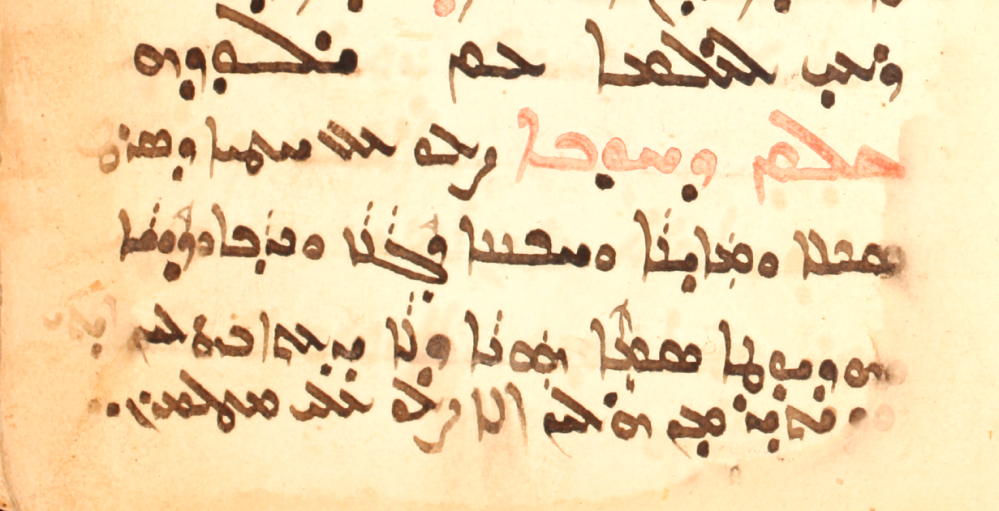

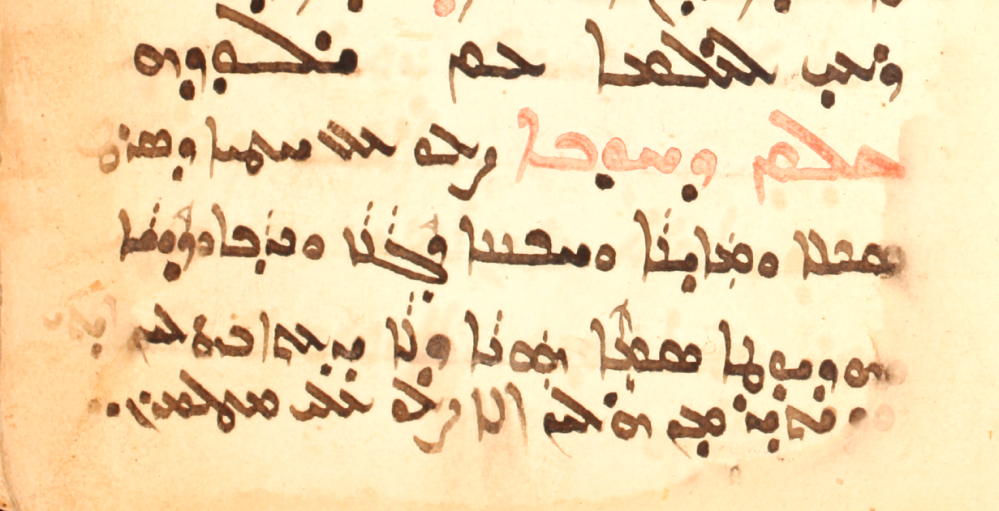

For some brief Friday fun, here’s part of a colophon that shows a little playful cleverness from a scribe. The manuscript CCM 58 (olim Mardin 7), a New Testament manuscript dated July 2053 AG (= 1742 CE) and copied in Alqosh, has a long colophon, including the following few colorful (literally and figuratively) lines near the end, at the bottom of one page and the top of the next:

CCM 58, f. 227v

CCM 58, f. 228r

That is:

Lord, may the payment of the five twins that have toiled, worked, labored, and planted good seed in a white field with a reed from the forest not be refused, but may they be saved from the fire of Gehenna! Yes, and amen!

The “five twins” are the scribe’s ten fingers, the “good seed” is the writing, the “white field” is the paper, and the “reed” is the pen. At least some of this imagery is not unique to this manuscript. In any case we have a memorable way of thinking about a scribe’s labor.

From p. 13 of the English edition mentioned at left.

Lately I stumbled upon an Arabic translation of John Bunyan’s (1628-1688) classic work of English religious literature, The Pilgrim’s Progress, on Google Books, in Arabic called Kitāb siyāḥat al-masīḥī. I don’t know the translator, but the date of the translation seems to be 1868. Now there is a copy here at archive.org; one of many English editions is available here.

To give an idea of the Arabic version, here are a few passages from the beginning of the book, with page numbers for the Arabic copy. The first paragraph is particularly fine.

As I walk’d through the wilderness of this world, I lighted on a certain place where was a Den, and I laid me down in that place to sleep; and as I slept, I dreamed a Dream. I dreamed, and behold I saw a Man cloathed with Rags, standing in a certain place, with his face from his own house, a Book in his hand, and a great Burden upon his back. I looked, and saw him open the Book, and read therein; and as he read, he wept and trembled; and not being able longer to contain, he brake out with a lamentable cry, saying, What shall I do?

p. 3

بينما انا عابر في تيه هذا العالم وجدت كهفًا في مكان فاستظلت به. ثم اخذتني سنة النوم فنمت واذا برجل قد ترآءى لي في الحلم لابسًا رثّة ووجهه منحرف عن بيته وعلى ظهره حمل ثقيل وفي يده كتاب قد فتحه وطفق يقرأ فيه. وعند ذلك بكى مرتعدًا ولم يقدر ان يضبط نفسه فصرخ مولولًا وقال ماذا اعمل

___________________

So I saw in my Dream that the Man began to run. Now he had not run far from his own door, but his Wife and Children, perceiving it, began to cry after him to return, but the Man put his fingers in his ears, and ran on, crying, Life! Life! Eternal Life! So he looked not behind him, but fled towards the middle of the Plain.

pp. 7-8

قال صاحب الرؤيا ثم رايت ذلك الرجل وكان يقال له المسيحي قد اخذ في الركض وما ابعد الا قليلًا عن داره حتى راته زوجته واولاده فصاحوا به يريدون ان يردّوه فسدّ اذنيه واشتدّ في عدوه وهو يقول الحيوة الحيوة حيوة الابد ولم يلتفت الى ورائه بل هرب الى وسط تلك البقعة

___________________

Chr. I seek an Inheritance incorruptible, undefiled, and that fadeth not away, and it is laid up in Heaven, and safe there, to be bestowed at the time appointed, on them that diligently seek it. Read it so, if you will, in my book.

Obst. Tush, said Obstinate, away with your Book; will you go back with us or no?

Chr. No, not I, said the other, because I have laid my hand to the Plow.

Obst. Come then, Neighbor Pliable, let us turn again, and go home without him; there is a company of these craz’d-headed coxcombs, that, when they take a fancy by the end, are wiser in their own eyes than seven men that can render a reason.

pp. 9-10

قال اني اطلب ميراثًا لا يبلى ولا يتدنس ولا يضمحلّ وهو مذخور في السماء بامن ليعطى في المقت المعيَّن لمن يطلبه باجتهاد. وان كنت في ريب من ذلك فافحص عنه في كتابي هذا تجده.

فقال اسكت ودعنا من كتابك اترجع معنا ام لا

قال كلّا لاني وضعت يدي على المحرث

فقال المعاند لصاحبه اذن نرجع وحدنا لانه يوجد جماعة من هولاء المجانين الذين اذا تخيّلوا سيـٔا يكونون عند انفسهم احكم من سبعة رجال متفلسفين

___________________

I can better conceive of them with my Mind, than speak of them with my Tongue: but yet, since you are desirous to know, I will read of them in my Book.

p. 12

قال المسيحي ان تصوّرها بالفكر ايسر عليّ من وصفها باللسان ولكن لاجل اهتمامك في معرفتها اقرأ لك شرحها في كتابي

Below are two similar, but not identical, ownership notes for Chaldean Patriarch Yawsep II (1667-1713) in seventeenth-century manuscripts from the Chaldean Cathedral of Mardin (recently mentioned here), both, as it happens, copies of The Book of Sessions (Ktābā d-bēt mawtbē), dated 1653 (№ 47) and 1672 (№ 48) and both copied at the Monastery of Mar Pethion in Amid (Diyarbakır). As often in ownership notes, there is also a curse against any would-be thieves. An English translation follows each image.

CCM 47, f. 212v

This Book of Sessions is the property of our exalted father, Mar Yawsep II, Patriarch of the Chaldeans. May whoever keeps it for himself secretly or in theft be excommunicated!

CCM 48, f. 273v

This Book of Sessions is the property of our exalted father, Mar Yawsep II, Patriarch of the Chaldeans. May the wrath of God remain on whoever keeps it for himself secretly or in theft! Amen!

Lately I have been cataloging a group of manuscripts from Saint Mark’s Monastery, Jerusalem, that have homiletic contents, especially the mēmrē of Jacob of Serug, including some that are hitherto unpublished. One of these manuscripts is SMMJ 162, from the late 19th or early 20th century. I don’t mention it here so much for the texts the scribe penned into it, but rather for a little colophon left at the end of Jacob’s Mēmrā on Love (cf. Bedjan, vol. 1, 606-627), f. 181r:

SMMJ 162, f. 181r

Pray for the sinner who has written [it], a fool, lazy, slothful, deceitful, a liar, wretched, stupid, blind of understanding, with no knowledge of these things, [nor] more than these things, but pray for me for our Lord’s sake!

Almost from the beginning of my time cataloging at HMML, I have been collecting excerpts of scribal notes and colophons that I found interesting for some reason or other, one such reason being the extreme self-loathing and self-deprecation that scribes not uncommonly trumpet. The cases in which scribes go on and on with adjectives or substantives of negative sentiment can elicit almost a humorous reaction, but scribes who do this do give their readers some semantically related vocabulary examples all in one spot!

NB: If interested, see my short article in Illuminations, Spring 2012, pp. 4-6, available here, for a popular presentation on colophons.

While cataloging an undated, late manuscript from Saint Mark’s Monastery (Jerusalem) today, I came across this page spread, each page showing a correction in the scribe’s hand.

SMMJ 165, ff. 6v-7r

Homer nods and copyists sleep: scribes old and new, like typesetters and typists, have been bound to occasionally slip into error, whether by letter, word, or line. Here on the right (f. 6v), four lines from the bottom, the scribe indicates that he — the odds are that the scribe was male, but it could have been a female scribe — first erroneously copied the word tešbḥātēh by transposing B and Ḥ, so it was a mistake of a letter leading to an incorrect word. On the left (f. 7r), the scribe at first omitted (probably) two lines, and he adds them into the margin. Both mistakes are signaled by a variously oriented sign similar to ÷. Although their function is not the same, it is easy to be reminded a little of the Aristarchian or Hexaplaric signs (Field, Origenis Hexaplorum quae supersunt, vol. 1, lii-lx; Swete, Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek, 69-73).

Proofreading is hardly relished by any one, whether a centuries-old scribe or today’s or tomorrow’s writer with a keyboard and screen, but seizing and adequately rectifying an error, whether by marking the error and pointing to the correction, as here, or by wholly obliterating the mistake and only giving the proper reading, at least goes a long way toward repaying the time spent doing it!

I have often enough here referred to colophons in Syriac and Arabic, but here is a simple example of one in Gǝʿǝz, from The Beheading of John the Baptist in EMML 2514 (written in the 1380s CE), f. 43r.

EMML 2514, f. 43r

In English:

Finished is the Combat [gädl] of the holy and elect John. May his prayer and blessing protect us forever and ever, amen!

May Christ have mercy in the kingdom of heaven on the one who has copied it, the one who has commissioned its copying, the one who has read it, and the one who has heard its words, through the prayer of the holy virgin, Mary, John the Baptist, and all the saints and martyrs, forever and ever, amen.

The operative vocabulary here is:

- täfäṣṣämä to be completed

- ṣäḥafä to write

- aṣḥafä to have someone write

- anbäbä to read

- sämʿa to hear

And, as usual, there is a wish that this or that saint’s prayer (ṣälot) and blessing (bäräkät) protect (ʿaqäbä) the scribe, etc.

A typological study of colophons in eastern Christian manuscripts from all the languages has, as far as I know, yet to be written, but it would be a worthwhile topic of investigation.

Saint Mark’s, Jerusalem, 135 is dated Feb 1901 AG (= 1590 CE) and contains a copy of Bar ʿEbrāyā’s Candelabrum of the Sanctuary (Mnārat Qudšē). It was copied at Dayr Al-Zaʿfarān by Behnām b. Šemʿon b. Ḥabbib of Arbo. From a much later note immediately after the colophon we learn that this scribe was made metropolitan of Jerusalem in 1901 AG and died in 1925 AG. Who wrote this later note? None other than Ignatius Afram Barsoum (1887-1957; see GEDSH, 62, including a photo). On the following page, there are three more notes by Barsoum, all autobiographical.

Notes by Barsoum at the end of SMMJ 135.

English’d:

In the year 1913 AD I visited the tomb of the savior and I spent two months in our monastery, that of Saint Mark, while I — the weakest of monks and the least of priests, Afram Barsoum of Mosul, alumnus of the Monastery Mār Ḥnānyā [Dayr Al-Zaʿfarān] — was using the old books [there]. Please pray for me!

In the year 1918 AD, on the 20th of Iyyār, I was elected metropolitan of the diocese of Syria, Damascus, Ḥoms, and their environs, and I was named Severius Afram.

In the year 1922 AD I again returned to Jerusalem and I took part in the consecration of the myron with Patriarch Eliya III on the 18th of Ēlul.

Notes like this are important for at least two reasons. First, they remind us that books have had their readers throughout their individual histories, that is, we are usually not the first readers since the time of the author or scribe to examine and study a book; rather, readers make contact with, or meet, books here and there along the way, with ourselves just one node in that continuum, and some of those readers leave their marks, wittingly or not, in the books. Second, these notes are a kind of archival document, in this case for the future patriarch Barsoum and for some goings-on in Syriac Orthodox circles in the first quarter of the twentieth century, and anyone studying the region in this time period might find something of interest here and in similar places. Once again, we see manuscripts as unique objects with unexpected finds!

I recently posted an image of a pastedown in SMMJ 68 that came from an older Syriac Gospel lectionary. While still looking through the Jerusalem collection, I found another manuscript with pastedowns (at both front and back) from a Syriac Gospel-book.

Front pastedown of SMMJ 159

Back pastedown of SMMJ 159

The front pastedown has the Markan passage on the Syrophoenician woman (Συροφοινίκισσα; see Sebastiano Ricci’s painting here) from the last word of Mk 7:24 to halfway through 7:29 (again the Peshitta, as SMMJ 68), and the back has Lk 19:29 (beginning at the third word) to 19:34 (third word from the end), but this time in the Ḥarqlean. (The only difference between these texts and those in Kiraz’s Comparative Edition of the Gospels, the Peshitta of which is based on the edition of Pusey and Gwilliam, are at Mk 7:25 [w-ʾit here, but d-ʾit in the printed ed.] and 7:26 [Phoenicia spelled with final yod here, ālap in the printed ed.].) A comparison of these two extraneous pages from SMMJ 159 with the one from SMMJ 68 quickly reveals their origin in the same manuscript. Apparently this Gospel lectionary was at Saint Mark’s and no longer being used, probably too damaged to be of practical use, and apart from their original peers these three folios found new life in SMMJ 68 and 159. Like the former Jerusalem manuscript, the latter, according to a note in Arabic at the beginning, was repaired in October, 1910.

“A new critical edition of the Peshitta Gospels is needed, though the quantity of Peshita mss. renders this a formidable task.” So say R.B. ter Haar Romeny and C.E. Morrison in their entry on the Peshitta in GEDSH (p. 330). This manuscript, now much reduced and scattered, more folios of which might appear elsewhere lurking at the beginning or end of manuscripts at Saint Mark’s, adds to that quantity of Peshitta manuscripts: for Mark in the front pastedown of SMMJ 159, and for John and Matthew in the front pastedown of SMMJ 68. Not that these particular Syriac Gospel witnesses are all that unique or interesting, but they do serve as a reminder of the surprises manuscripts can offer. And, from a different angle, the script here has much to appreciate for its clarity and simplicity; it would make an easy exercise for beginning students to practice their reading skills.

One of the most visually striking manuscripts, even though it is not very colorful, in the collection of the Near East School of Theology, Beirut, is AP 38, thanks to its drawings in the second part of the work. There are animals (including the human body), plants, mechanical diagrams, a map, and other figures. It is not an old book at all, but it deserves a facsimile edition for its unique visual presentations. An anonymous work, it was apparently translated from Turkish, which version itself was translated from an English book (cf. J.W. Pollock, “Catalogue of Manuscripts of the Library of the Near East School of Theology,” Near East School of Theology Theological Review 4 [1981]: 69). Below is one example of the several diagrams (pt. 2, p. 11):

NEST AP 38, pt. 2, p. 11

The caption reads:

hāḏihi ṣūratu ṭurumbā [sic] ‘l-māʾi allaḏī tanšulu ‘l-māʾa min al-baḥri wa-tūṣiluhu ilá ‘l-amākini ‘l-baʿīdati ka-ma tarāhā marsūmatan hākaḏa hāhunā

This is a picture of a water-pump that takes water from the sea and conducts it to faraway places, as you see drawn here.

(For ṭurumba/ṭurumbā, cf. Italian trompa, Turkish tulumba.)