Archive for the ‘Syriac’ Category

CFMM 167 and 165 (in that order) are two small notebooks from the late 19th or early 20th century. There is no explicit date, nor did the scribe give a name, but the writing is very clear. Included in the collection are some of Jacob of Serugh’s homilies against the Jews (№№ 1-5, 7, so numbered); this cycle of homilies was edited by Micheline Albert, Jacques de Saroug. Homélies contre les Juifs, PO 38. There are also a few other homilies, the most important of which are the first four copied in CFMM 167, all of which have never been published, although they are known from the Dam. Patr. manuscripts and from Assemani’s list of homilies in Bibliotheca Orientalis I: pp. 325-326, no. 174 = the second hom. below. (For a list of incipits of Jacob’s homilies, see Brock in vol. 6 of the Gorgias edition of Bedjan, The Homilies of Mar Jacob of Sarug, [2006], pp. 372-398.)

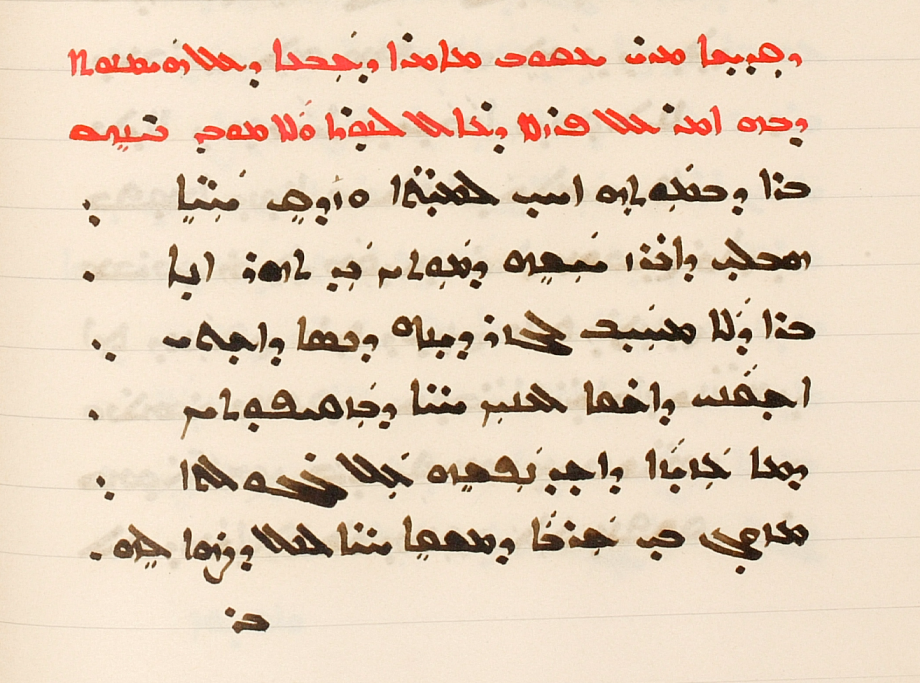

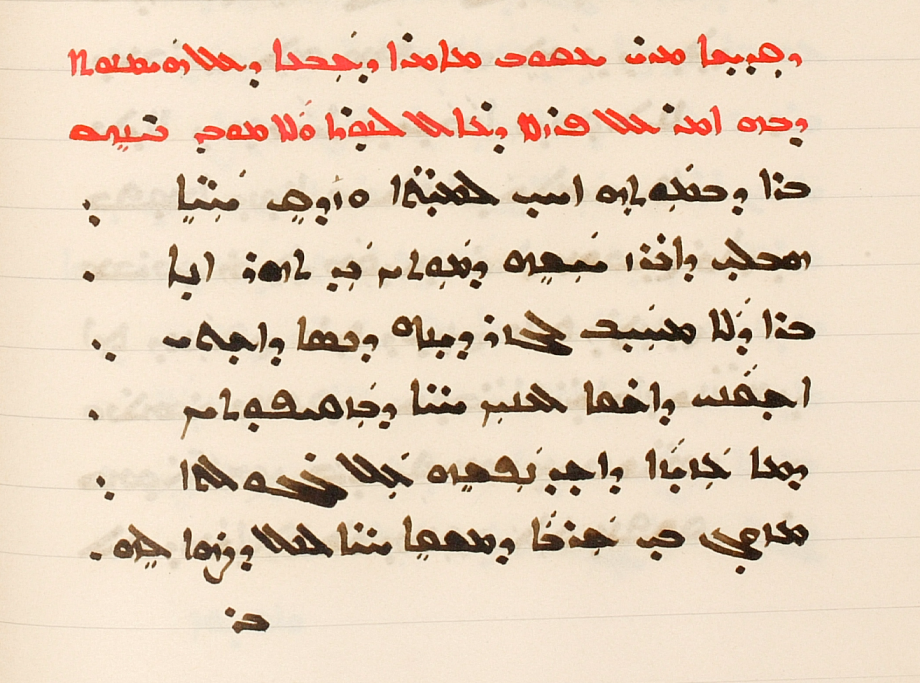

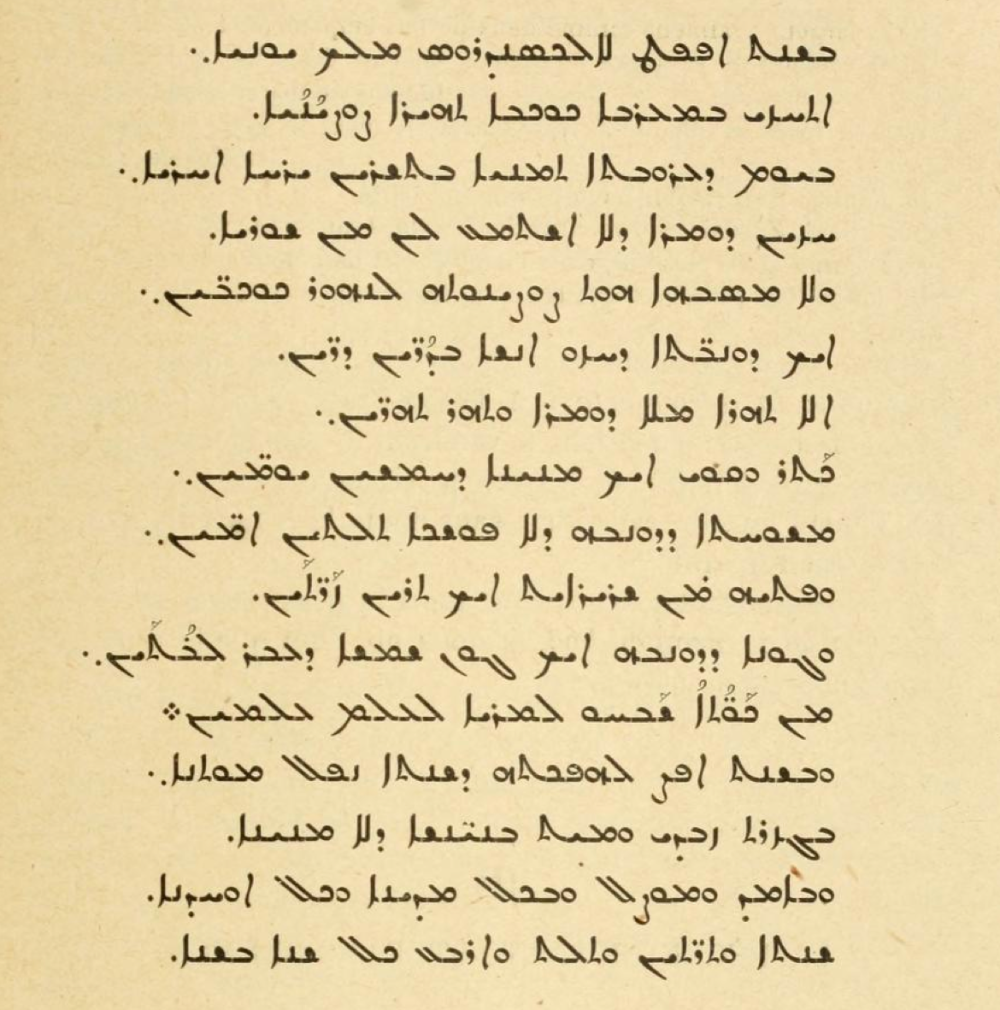

CFMM 167, p. 22

pp. 1-22 Memra on the Faith, 6

- Syriac title ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܫܬܐ ܕܥܠ ܗܝܡܢܘܬܐ

- Incipit ܐܚ̈ܝ ܢܥܪܘܩ ܡܢ ܟܣܝ̈ܬܐ ܕܠܐ ܡܬܒܨ̈ܝܢ

pp. 22-56, Memra on the Faith, 7, in which he Talks about the Iron that Enters the Fire and does not Lose its Nature

- Syriac title ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܫܒܥܐ ܕܥܠ ܗܝܡܢܘܬܐ ܕܒܗ ܐܡܪ ܥܠ ܦܪܙܠܐ ܕܥܐܠ ܠܢܘܪܐ ܘܠܐ ܡܘܒܕ ܟܝܢܗ

- Incipit ܒܪܐ ܕܒܡܘܬܗ ܐܚܝ ܠܡܝ̈ܬܐ ܘܙܕܩ ܚܝ̈ܐ

pp. 56-72, Memra on the Faith, in which He Teaches that the Way of Christ Cannot be Investigated

- Syriac title ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܗܝܡܢܘܬܐ ܕܒܗ ܡܘܕܥ ܥܠ ܐܘܪܚܗ ܕܡܫܝܚܐ ܕܠܐ ܡܬܒܨܝܐ

- Incipit ܐܝܟ ܕܠܫܘܒܚܟ ܐܙܝܥ ܒܝ ܡܪܝ ܩܠܐ ܪܡܐ

pp. 72-68bis, Memra on the Faith, 10

- Syriac title ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܣܪܐ ܕܥܠ ܗܝܡܢܘܬܐ

- Incipit ܢܫܠܘܢ ܣܦܪ̈ܐ ܡܢ ܥܘܩܒܗ ܕܒܪ ܐܠܗܐ

As a special treat, here is the cover of this manuscript, with a 19th-cent. image of the Golden Horn (Turkish Haliç) and the Unkapanı Bridge (see now Atatürk Bridge):

Front cover of CFMM 167

The Turkish beneath the French is roughly Haliç Dersaadet manzarından Unkapanı köprüsü. Dersaadet is one of the old names of Istanbul.

One of the pleasures of cataloging manuscripts is learning about authors and texts that are relatively little known. One such Syriac author is Athanasios (Abū Ġalib) of Ǧayḥān (Ceyhan). Two fifteenth-century manuscripts, CFMM 417 and 418, which I have recently cataloged, each contain different texts attributed to him. Barsoum surveys his life and work briefly in Scattered Pearls (pp. 441-442), and prior to that Vosté wrote an article on him; more recently Vööbus and Carmen Fotescu Tauwinkl have further reported on him. (See the bibliography below; I have not seen all of these resources.) According to Barsoum, he died in 1177 at over 80 years old. As far as I know, none of his work has been published.

The place name associated with this author is the Turkish Ceyhan. The Syriac spelling of the place in the Gazetteer has gyḥʾn, but in both of these manuscripts it is gyḥn. The former is probably an imitation of the Arabic-script spelling, while the form without ālap in the manuscripts still indicates ā in the second syllable by means of an assumed zqāpā.

Now for the CFMM texts.

CFMM 417, pp. 465-466

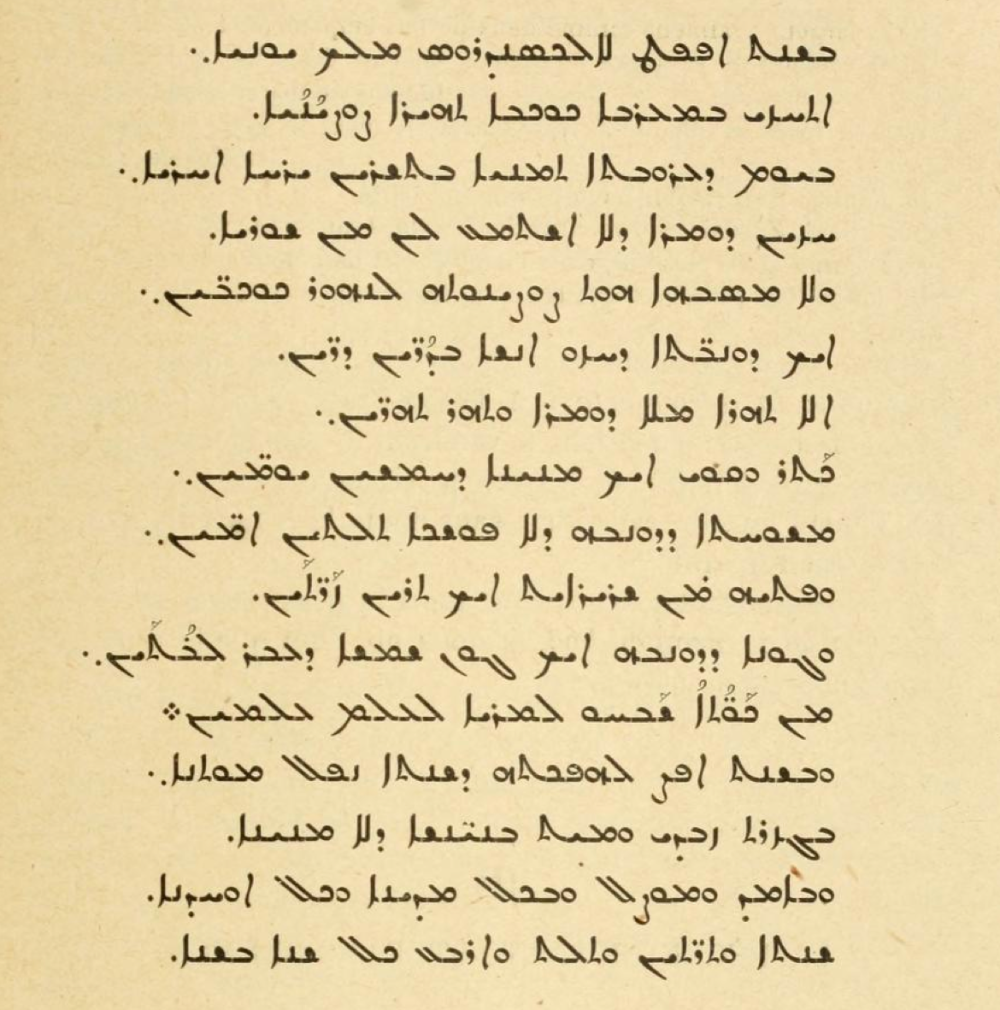

An untitled monastic selection. These two pages make up the whole of this short text. As you can see, it follows something from Isaac of Nineveh, and it precedes Ps.-Evagrius, On the Perfect and the Just (CPG 2465 = Hom. 14 of the Liber Graduum). The manuscript is dated March, 1785 AG (= 1474 CE).

CFMM, p. 465

CFMM 417, p. 466

****

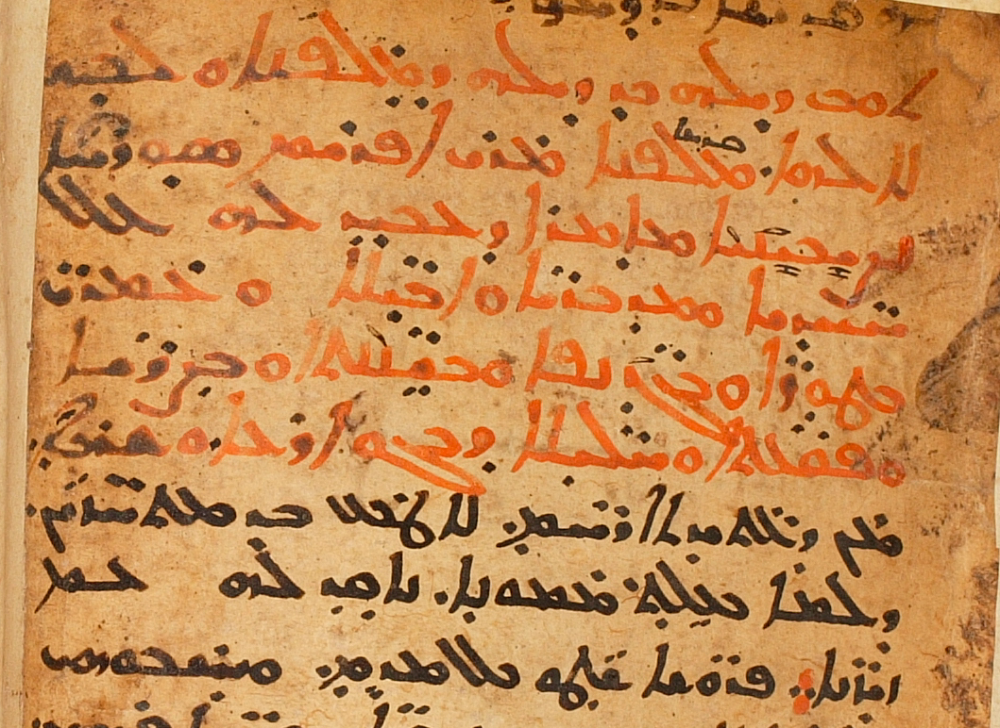

CFMM 418, ff. 235v-243v

Excerpts “from his teaching”. Here are the first and last pages of the text. This longer text follows Isaac of Nineveh’s Letter on how Satan Takes Pains to Remove the Diligent from Silence (ff. 223v-235v, Eggartā ʿal hāy d-aykannā metparras Sāṭānā la-mbaṭṭālu la-ḥpiṭē men šelyā) and precedes some Profitable Sayings attributed to Isaac. This manuscript — written by more than one scribe, but at about the same time, it seems — is dated on f. 277v with the year 1482, but the 14- is to be read 17-, so we have 1782 AG (= 1470/1 CE; cf. Vööbus, Handschriftliche Überlieferung der Mēmrē-Dichtung des Jaʿqōb von Serūg, III 97).

CFMM 418, f. 235v

CFMM 418, f. 243v

Bibliography

Tauwinkl, Carmen Fotescu, “Abū Ghālib, an Unknown West Syrian Spiritual Author of the XIIth Century”, Parole de l’Orient 36 (2010): 277-284.

Tauwinkl, Carmen Fotescu, “A Spiritual Author in 12th Century Upper Mesopotamia: Abū Ghālib and his Treatise on Monastic Life”, Pages 75-93 in The Syriac Renaissance. Edited by Teule, Herman G.B. and Tauwinkl, Carmen Fotescu and ter Haar Romeny, Robert Bas and van Ginkel, Jan. Eastern Christian Studies 9. Leuven / Paris / Walpole, MA: Peeters, 2010.

Vööbus, Arthur, History of Asceticism in the Syrian Orient: A Contribution to the History of Culture in the Near East, III, CSCO 500, Subs. 81. Louvain: Secrétariat du CorpusSCO, 1988, pp. 407-410.

Vööbus, Arthur, “Important Discoveries for the History of Syrian Mysticism: New Manuscript Sources for Athanasius Abû Ghalîb”, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 35:4 (1976): 269-270.

Vosté, Jacques Marie, “Athanasios Aboughaleb, évêque de Gihân en Cilicie, écrivain ascétique du XIIe siècle”, Revue de l’Orient chrétien III, 6 [26] (1927-1928): 432-438. Available here.

(Apologia: Some background on the writing of this post. I wrote most of this post and translated the text when under the impression that there was not yet any English translation of it. I had stumbled upon Nau’s article while perusing the Syriac contents of ROC at Aramaico. But on the day I was finishing up the post, I happened to be looking at something completely unrelated in The Hidden Pearl, vol. 2, and I found to my surprise that there was a partial translation of this text in English! (If I had noticed it there before, I’d forgotten.) It will be found there on p. 258. Even though the translation below is not, then, the first English witness to this interesting text, it is, I think, the first complete English translation, and so I have decided to go ahead and share it. Being freely accessible online, it may also bring word of this text to a broader audience, and the other remarks and the vocabulary list will perhaps be of interest and use to some readers.)

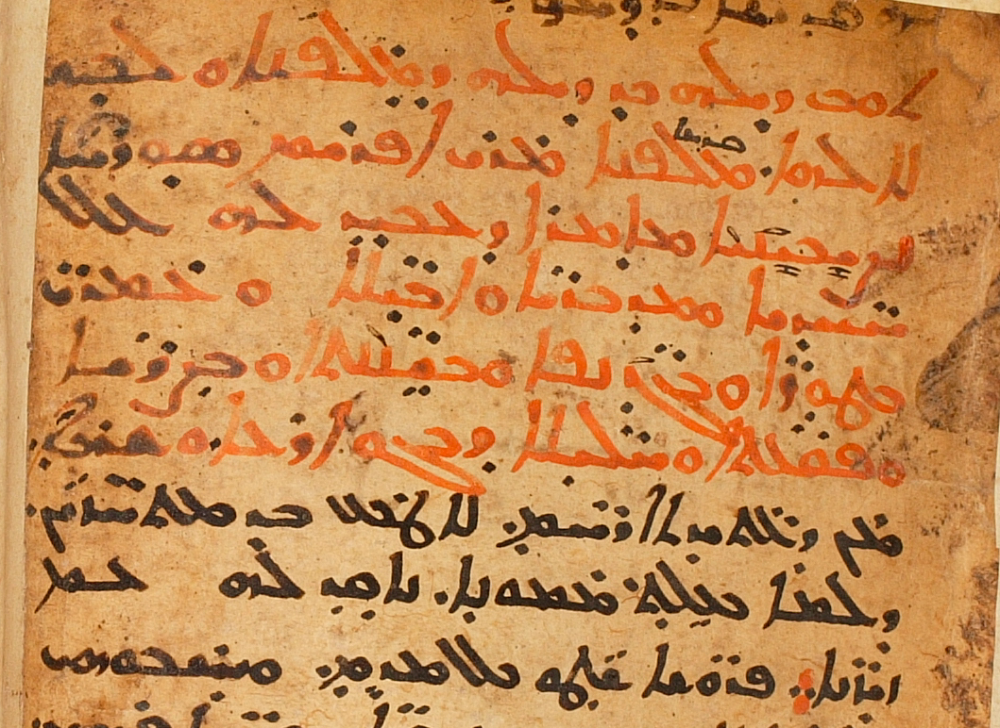

Some time ago I published and translated two related notes in Syriac on some meteorological events from the sixteenth century (see also a later weather report in Syriac here). It happens that a more momentous sixteenth-century cosmic event, complete with a plague, was also recorded in Syriac: the Great Comet of 1577. The industrious François Nau first brought attention to the text with his publication and FT in his “Une description orientale de la comête de novembre de 1577,” ROC 27 (1929-1930): 212-214 (available here). Below I give the Syriac text, which is written in rhymed prose, followed by an English translation (which is not in rhymed prose!).

Comets are discussed here and there in Syriac cosmological literature. For example, in the Syriac version of the De Mundo, Sergius of Rēšʿaynā simply uses the Greek word (qwmṭʾ, qwmṭs; see McCollum, A Greek and Syriac Index to Sergius of Reshaina’s Version of the De Mundo, p. 104). Similar to the term below, Jacob bar Shakko has kawkbē ṣuṣyānāyē (see F. Nau, “Notice sur le livre des trésors de Jacques de Bartela, Évèque de Tagrit,” Journal Asiatique, 9th series, 7 (1896): 286-331, here 328). Similar is Bar ʿEbrāyā’s language in his “Book of Meteorology” in the Butyrum Sapientiae; see H. Takahashi, Aristotelian Meteorology in Syriac, pp. 148-149, 190-191. Via Bar ʿEbrāyā, too, we have the same terminology in a Syriac fragment based on “Ptolemy’s” Liber fructus; the fragment begins, āmar gēr Pṭolomos ba-ktābēh haw d-asṭrologia pērā qrāy(hy) (see F. Nau, “Un fragment syriaque de l’ouvrage astrologique de Claude Ptolémée intitulé le livre du fruit,” ROC 28 (1931-1932): 197-202, avail. here). (See further Payne Smith, Thes. Syr. col. 3382.)

Syriac text from ROC 27, p. 213

The events here are dated beginning in Tišrin II, 1889 AG, which corresponds to November, 1577 CE. The plague at the end of the text is dated throughout the years 1890-1893 AG (= 1578/9-1581/2 CE).

In the year 1889 of Alexander, Greek king,

A marvelous comet appeared in the west.

On Friday, the 8th of the month Tišrin II,

We saw a wonder that we had never before heard of,

And its cometness was not like the light of stars,

[Nor] as the tails [of comets] that people had seen in various generations:

No, it was a marvel full of wonder and a marvel of marvels.

It lasted and continued about fifty days.

The size of its tail was undoubtedly thirty cubits,

And its width was surely about two of our spans.

The color of its tail was like the color of the sun, which crosses our houses.

From the windows praise the Lord forever!

And in the year 1890 [AG], in the next year, a plague occurred

In Gāzrat Zabday, and numberless people died,

Also in Amid, Mosul, and in every city and every province:

[It lasted] a year, two, three, and four, each and every year.

For students of Syriac, here is a running list of vocabulary to the text:

ṣuṣyānāyā lock-like, having locks (of hair) < ṣuṣitā lock of hair (cf. “comet” κομήτης < κόμη)

dummārā marvel, wonder

sbh D to liken (here pass. ptcp)

ṣuṣyānutā cometness

dunbtā tail

te/ahrā wonder, miracle

puššākā uncertainty (d-lā puššākā certainly, undoubtedly)

ammtā cubit

zartā span (½ cubit)

ptāyā width

gawnā (cstr ES gon, WS gwan; see Nöldeke § 98) color, manner

bāttayn pl of baytā + 1cp

kawwtā window (in BibAram Dan 6:11)

hepktā d-ša(n)tā the following year

mawtānā plague, pestilence

Gāzrat Zabday cf. Payne Smith, Thesaurus Syriacus, cols. 702-703; Wright, Cat. Syr. Brit. Mus., vol. 3, p. 1339)

uḥdānā province

šnā abs of ša(n)tā

DCA (Chaldean Diocese of Alqosh) 62 contains various liturgical texts in Syriac. It is a fine copy, but the most interesting thing about the book is its colophon. Here first are the images of the colophon, after which I will give an English translation.

DCA 62, f. 110r

DCA 62, f. 110v

English translation (students may see below for some lexical notes):

[f. 110r]

This liturgical book for the Eucharist, Baptism, and all the other rites and blessings according to the Holy Roman Church was finished in the blessed month of Adar, on the 17th, the sixth Friday of the Dominical Fast, which is called the Friday of Lazarus, in the year 2150 AG, 1839 AD. Praise to the Father, the cause that put things into motion and first incited the beginning; thanks to the Son, the Word that has empowered and assisted in the middle; and worship to the Holy Spirit, who managed, directed, tended, helped, and through the management of his care brought [it] to the end. Amen.

[f. 110v]

I — the weak and helpless priest, Michael Romanus, a monk: Chaldean, Christian, from Alqosh, the son of the late deacon Michael, son of the priest Ḥadbšabbā — wrote this book, and I wrote it as for my ignorance and stupidity, that I might read in it to complete my service and fulfill my rank. Also know this, dear reader: that from the beginning until halfway through the tenth quire of the book, it was written in the city of Siirt, and from there until the end of the book I finished in Šarul, which is in the region of the city of Erevan, which is under the control of the Greeks (?), when I was a foreigner, sojourner, and stranger in the village of Syāqud.

The fact that the scribe started his work in Siirt (now in Turkey), relocated, then completed his work, is of interest in and of itself. As for the toponyms, Šarul here must be Sharur/Şərur, now of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (an exclave of Azerbaijan), which at the time of the scribe’s writing was under Imperial Russian control, part of the Armenian Province (Армянская область), and prior to that, part of the Safavid Nakhchivan Khanate, which, with the Erevan Khanate, Persia ceded to Russia at the end of the Russo-Persian War in 1828 with the Treaty of Turkmenchay (Туркманчайский договор, Persian ʿahd-nāme-yi Turkamānčāy). The spelling of Erevan in Syriac above matches exactly the spelling in Persian (ايروان). When the scribe says that Šarul/Sharur/Şərur is in the region of Erevan, he apparently means the Armenian Province, which contained the old Erevan Khanate. He says that the region “is under the control of the Greeks” (yawnāyē); this seems puzzling: the Russians should be named, but perhaps this is paralleled elsewhere. For Syāqud, cf. Siyagut in the Syriac Gazetteer.

See the Erevan and Nakhchivan khanates here called respectively Х(анст)во Ереванское and Х(анст)во Нахичеванское, bordering each other, both in green at the bottom of the map near the center.

For Syriac students, here are some notes, mostly lexical, for the text above:

- šql G sākā w-šumlāyā to be finished (hendiadys)

- ʿyādā custom

- ʿrubtā eve (of the Sabbath) > Friday

- zwʿ C to set in motion

- ḥpṭ D incite (with the preposition lwāt for the object)

- šurāyā beginning

- tawdi thanks (NB absolute)

- ḥyl D to strengthen, empower

- ʿdr D to help, support

- mṣaʿtā middle

- prns Q to manage, rule (cf. purnāsā below)

- dbr D to lead, guide

- swsy Q to heal, tend, foster

- swʿ D to help, assist, support

- ḥartā end

- mnʿ D to reach; to bring

- purnāsā management, guardianship, support (here constr.)

- bṭilutā care, forethought

So we have an outline of trinitarian direction in completing the scribal work: abā — šurāyā; brā — mṣaʿtā; ruḥ qudšā — ḥartā.

- mḥilā weak

- tāḥobā feeble, wretched

- mnāḥ (pass. ptcp of nwḥ C) at rest, contented

- niḥ napšā at rest in terms of the soul > deceased (the first word is a pass. ptcp of nwḥ G)

- mšammšānā deacon

- burutā stupidity, inexperience

- hedyoṭutā stupidity, simplicity (explicitly vocalized hēdyuṭut(y) above)

- šumlāyā fulfilling

- mulāyā completion

- dargā office, rank

- qāroyā reader

- pelgā half, part

- kurrāsā quire

- šlm D to complete, finish

- nukrāyā foreigner

- tawtābā sojourner

- aksnāyā stranger

- qritā village

While cataloging the 15th-century manuscript CFMM 152 (on which see also here), I was struck by the long rubric of this mēmrā attributed to Ephrem.

CFMM 152, p. 156

(Students of Syriac may note the construct state before a preposition in ʿāmray b-ṭurē [Nöldeke, Gramm., § 206], as well as in the common epithet lbiš l-alāhā [Brockelmann, Lexicon Syriacum, 2d ed., 358a].)

Here with English glosses are the nouns in this rubric where monks may dwell. They can all be rocky areas, and there might be some semantic ambiguity and overlap with some of them.

- ṭurā mountain

- gdānpā ledge, crag

- šnāntā rock, crag, peak

- ṣeryā crack, fissure

- pqaʿtā crack (also valley)

- ḥlēlā crack

Brock’s list of incipits tells us that this mēmrā, possibly a genuine work of Ephrem, has been published by Beck in Sermones IV (CSCO 334-335 / Scr. Syr. 148-149, 1973), pp. 16-28. (Published earlier by Zingerle and Rahmani; there are two English translations, neither available to me at the moment.) The rubric in Beck’s ed. differs slightly from the one in this manuscript.

For comparison, here is another mēmrā attributed to Ephrem from a later manuscript, CFMM 157, p. 104. (see Beck, Sermones IV, pp. 1-16, for a published edition of the mēmrā).

CFMM 157, p. 104

This one has some of the same words, but the related addition terms are:

- mʿartā cave (pl. without fem. marker; see Nöldeke, Gramm., § 81)

- šqipā cliff

- pe/aʿrā cave

And so I leave you with these related Syriac terms, in case you wish to write a Syriac poem with events in rocky locales!

Here is a colophon from a manuscript I cataloged last week (CFMM 155, p. 378). It shares common features and vocabulary with other Syriac colophons, but the direct address to the reader, not merely to ask for prayer, but also to suggest that the reader, too, needs rescuing is less common. We often find something like “Whoever prays for the scribe’s forgiveness will also be forgiven,” but the phrasing we find in this colophon is not as common.

CFMM 155, p. 378

Brother, reader! I ask you in the love of Jesus to say, “God, save from the wiles of the rebellious slanderer the weak and frail one who has written, and forgive his sins in your compassion.” Perhaps you, too, should be saved from the snares of the deceitful one and be made worthy of the rank of perfection. Through the prayers of Mary the Godbearer and all the saints! Yes and yes, amen, amen.

Here are a few notes and vocabulary words for students:

- pāgoʿā reader (see the note on the root pgʿ in this post)

- ḥubbā Išoʿ should presumably be ḥubbā d-Išoʿ

- pṣy D to save; first paṣṣay(hy) D impv 2ms + 3ms, then tetpaṣṣē Dt impf 2ms

- mḥil weak

- tāḥub weak

- ākel-qarṣā crumb-eater, i.e. slanderer, from an old Aramaic (< Akkadian) idiom ekal qarṣē “to eat the crumbs (of)” > “to slander” (see S.A. Kaufman, Akkadian Influences on Aramaic, p. 63) (cf. διάβολος < διαβάλλω)

- ṣenʿtā plot (for ṣenʿātēh d-ākel-qarṣā cf. Eph 6:11 τὰς μεθοδείας τοῦ διαβόλου)

- mārod rebellious

- paḥḥā trap, snare

- nkil deceitful

- šwy Gt to be equal, to be made worthy, deserve

- dargā level, rank

- gmirutā perfection

In Sarjveladze-Fähnrich, 960a, s.v. რაკა (and 1167b, s.v. უთჳსესი), the following line is cited from manuscript A-689 (13th cent.), f. 69v, lines 20-23:

კითხვაჲ: რაჲ არს რაკა? მიგებაჲ: სიტყუაჲ სოფლიოჲ, უმშჳდესადრე საგინებელად უთჳსესთა მიმართ მოპოვნებული

Frage: Was ist Raka? Antwort: Ein grobes Wort, den nächsten Angehörigen gegenüber als leiser Tadel gebraucht.

This is a question-and-answer kind of commentary note on the word raka in Mt 5:22. There is probably something analogous in Greek or other scholia, but I have not checked. For this word in Syriac and Jewish Aramaic dialects, see Payne Smith 3973-3974; Brockelmann, LS 1488; DJPA 529b; and for JBA rēqā, DJBA 1078a (only one place cited, no quotation given). For the native lexica, see Bar Bahlul 1915 and the quotations given in Payne Smith.

For this word in this verse, the Syriac versions (S, C, P, H) all have raqqā, Armenian has յիմար (senseless, crazy, silly), and in the Georgian versions, the earlier translations have შესულებულ, but the later, more hellenizing translations have the Aramaic > Greek word რაკა on which the scholion was written. Before returning to the Georgian scholion above, let’s first have a look at parts of this verse in Greek and all of these languages. Note this Georgian vocabulary for below:

გან-(ხ)-უ-რისხ-ნ-ეს 3sg aor conj (the -ნ- is not the pl obj marker) განრისხება to become angry | ცუდად in vain, without cause | შესულებული dumbfounded, stupid | ცოფი crazy, fool

Part 1

- πᾶς ὁ ὀργιζόμενος τῷ ἀδελφῷ αὐτοῦ

- kul man d-nergaz ʿal aḥu(h)y iqiʾ

- ամենայն որ բարկանայ եղբաւր իւրում տարապ֊արտուց

- A89/A844 რ(ომე)ლი განხოჳრისხნეს ძმასა თჳსა [ცოჳ]დად

- Ad ყოველი რომელი განურისხნეს ძმასა თჳსსა ცუდად

- PA რომელი განურისხნეს ძმასა თჳსსა ცუდად

- At რომელი განურისხნეს ძმასა თჳსსა ცუდად

Part 2

- ὃς δ’ ἂν εἴπῃ τῷ ἀδελφῷ αὐτοῦ· ῥακά

- kul d-nēmar l-aḥu(h)y raqqā

- որ ասիցէ ցեղբայր իւր յիմար

- A89/A844 რ(ომელმა)ნ ხრქ(ოჳ)ას ძმასა თჳსსა შესოჳლებოჳლ

- Ad რომელმან ჰრქუას ძმასა თჳსსა: შესულებულ

- PA რომელმან ჰრქუას ძმასა თჳსსა რაკა

- At რომელმან ჰრქუას ძმასა თჳსსა რაკა

Part 3

- ὃς δ’ ἂν εἴπῃ· μωρέ

- man d-nēmar lellā (P, H; while S, C have šāṭyā)

- որ ասիցէ ցեղբայր իւր մորոս

- A89/A844 NA

- Ad და რომელმან ჰრქუას ძმასა თჳსსა: ცოფ

- PA რომელმან ჰრქუას ძმასა თჳსსა ცოფ

- At რომელმან ჰრქუას ძმასა თჳსსა ცოფ

So now we return to the scholion given above.

კითხვაჲ: რაჲ არს რაკა? მიგებაჲ: სიტყუაჲ სოფლიოჲ, უმშჳდესადრე საგინებელად უთჳსესთა მიმართ მოპოვნებული

- კითხვაჲ question

- მიგებაჲ answer

- სოფლიოჲ worldly (< სოფელი)

- უმშჳდეს-ად-რე < უმშჳდესი quiet, peaceful, calm adv + -რე a particle meaning “a little, slightly”

- საგინებელად to berate, chide, scold

- უთჳსესი neighbor, nearby person

- მოპოვნებული found

Finally, here is an English translation of the scholion:

Question: What is raka? Answer: An impolite word found [when one wants] to berate one’s neighbor in a slightly gentle way.

That is, according to the scholiast there are harsher, stronger vocatives with which to berate someone, but when just a little verbal aggression is needed, raka is the word to choose!

In Mt 19:24, Mk 10:25, and Lk 18:25 Jesus famously paints the difficulty of a rich person’s ability to get into the kingdom of God with the picture of a camel going through the eye of a needle. The strangeness of the image has not been lost on Gospel-readers from early on. Origen, followed by Cyril, reports that some interpreters took the word κάμηλος ≈ κάμιλος not as the animal, but as some kind of thick rope. This interpretation from Cyril is known also in Syriac, both in the Syriac translation of the Luke commentary, and in Bar Bahlul, and probably elsewhere. I noticed recently in my Georgian Gospel reading that the early translations also bear witness to the reading “rope”, but the later translations — not surprisingly, given the predominant hellenizing tendencies of the period — line up with the standard Greek reading, “camel”, in most (but not all!) places. Below I list a few of the Greek exegetical places, followed by the three synoptic Gospel verses in Greek, Armenian, and Georgian; I have translated into English everything quoted below except for the Greek Gospel verses. The Syriac versions (Old Syriac, Peshitta, Harqlean), at least in Kiraz’s Comparative Edition of the Syriac Gospels, all have “camel” (gamlā), not “rope” (e.g. ḥablā). As usual, for Armenian and Georgian I provide a few lexical notes. I’ve used the following abbreviations:

- A89 = the xanmeti text A89/A844, ed. Lamara Kajaia (not extant for the whole of the Gospel of text), at TITUS here (given in both asomtavruli and mxedruli)

- Ad = Adishi, at TITUS here

- At = Athonite (Giorgi the Hagiorite), at TITUS here

- Künzle = B. Künzle, Das altarmenische Evangelium / L’évangile arménien ancien, 2 vols. [text + Armenian-German/French lexicon (Bern, 1984)

- Lampe = G.W.H. Lampe, A Patristic Greek Lexicon

- PA = Pre-Athonite, see here at TITUS

- PG = Migne, Patrologia Graeca

As a side note, for the Qurʾān verse that cites the phrase in question, see the following:

- W. Montgomery Watt, “The Camel and the Needle’s Eye,” in C.J. Bleeker et al., eds., Ex Orbe Religionum: Studia Geo Widengren, vol. 2 (Leiden, 1972), pp. 155-158.

- Régis Blachère, “Regards sur un passage parallèle des Évangiles et du Coran,” in Pierre Salmon, ed., Mélanges d’Islamologie, volume dédié à la mémoire d’Armand Abel par ses collègues, ses élèves et ses amis (Leiden, 1974), pp. 69-73.

- M.B. Schub, “It Is Easier for a Cable to go through the Eye of a Needle than for a Rich Man to Enter God’s Kingdom,” Arabica 23 (1976): 311-312.

- Samir Khalil, “Note sur le fonds sémitique commun de l’expression ‘un chameau passant par le trou d’une aiguille’,” Arabica 25 (1978): 89-94.

- A. Rippin, “Qurʾān 7.40: ‘Until the Camel Passes through the Eye of the Needle'” Arabica 27 (1980): 107-113.

A similar phrase with “elephant” (pīlā) instead of “camel” appears in the Talmud: see Strack-Billerbeck, Kommentar, vol. 1, p. 828, and Sokoloff, Dict. of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, s.v. qwpʾ.

Some Greek and Syriac exegetical and lexical references

Origen, Fragment on Mt 19:24: οἱ μὲν τὸ σχοινίον τῆς μηχανῆς, οἱ δὲ τὸ ζῷον (cited in Lampe, 700a, s.v. κάμηλος)

Some [say the word means] the rope of some apparatus, others [say it means] the animal [the camel].

Cyril of Alexandria, Fragment on Mt 19:24 (PG 72: 429) Κάμηλον ἐνταῦθά φησιν, οὐ τὸ ζῶον τὸ ἀχθοφόρον, ἀλλὰ τὸ παχὺ σχοινίον ἐν ᾧ δεσμεύουσι τὰς ἀγκύρας οἱ ναῦται.

He says that kámēlos here is not the beast of burden, but rather the thick rope with which sailors tie their anchors.

Cyril, Comm. on Lk 18:23 (PG 72: 857) Κάμηλον, οὐ τὸ ζῶον, ἀλλὰ τὸ ἐν τοῖς πλοίοις παχὺ σχοινίον.

Kámēlos is not the animal, but rather the thick rope found in boats.

With this Greek line from the Luke commentary we can compare the Syriac version, ed. Payne Smith, p. 338.15-17: gamlā dēn āmar law l-hāy ḥayutā mālon ellā l-ḥablā ʿabyā. ʿyāda (h)w gēr l-hānon d-šappir yādʿin d-neplḥun b-yammā da-l-hālēn ḥablē d-yattir ʿbēn gamlē neqron.

He says gamlā, [meaning] not the animal, but rather a thick rope, for those who know well how to plow the sea are accustomed to call the very thick ropes that they use gamlē.

One more place in Syriac attributed to Cyril has this interpretation, a few lines in the fragmentarily preserved work Against Julian (CPG 5233), ed. E. Nestle in Karl Johannes Neumann, Iuliani imperatoris librorum contra Christianos quae supersunt (Leipzig, 1880), here p. 56, § 21: d-qaddišā Qurillos, men mēmrā d-16 d-luqbal Yuliyanos raššiʿā. mqabbel hākēl l-taḥwitā: ḥrurā da-mḥaṭṭā w-gamlā, w-law ḥayutā a(y)k d-asbar Yuliyanos raššiʿā wa-skal b-kul w-hedyoṭā, ellā mālon ḥablā ʿabyā da-b-kul ellpā, hākanā gēr it ʿyādā d-neqron ennon aylēn d-ilipin hālēn d-elpārē.

Cyril, from book 16 of [his work] Against Julian the Wicked. He accepts, then, the example: the eye of the needle and the gamlā, but not the animal, as the wicked, completely stupid, and ignorant Julian thought, but rather the thick rope that is on every ship, for thus those sailors who are expert are accustomed to call them.

Theophylact of Ohrid, Ennaratio on Mt (PG 123: 356): Τινὲς δὲ κάμηλον οὐ τὸ ζῷόν φασιν, ἀλλὰ τὸ παχὺ σχοινίον, ᾧ χρῷνται οἱ ναῦται πρὸς τὸ ῥίπτειν τὰς ἀγκύρας.

Some say that kámēlos is not the animal, but rather the thick rope that sailors use to cast their anchors.

Suda, Kappa № 282: Κάμηλος: τὸ ζῷον. … Κάμιλος δὲ τὸ παχὺ σχοινίον.

Kámēlos: the animal. … Kámilos a thick rope.

Ps.-Zonaras, Lexicon: Κάμηλος. τὸ ἀχθοφόρον ζῶον. κάμηλος καὶ τὸ παχὺ σχοινίον, ἐν ᾧ δεσμεύουσι τὰς ἀγκύρας οἱ ναῦται. ὡς τὸ ἐν εὐαγγελίοις· κάμηλον διὰ τρυπήματος ῥαφίδος διελθεῖν.

Kámēlos: the beast of burden. Kámēlos is also the thick rope with which sailors tie their anchors, as in the Gospels: “for a kámēlos to go through the eye of a needle.”

As mentioned above, Cyril’s report on the verse re-appears among other things in Bar Bahlul: ed. Duval, coll. 500-501, s.v. gamlā: gamlā tub maraš [sic! cf. maras]. ba-ṣḥāḥā Qurillos gamlā qārē l-ḥablā ʿabyā d-āsrin bēh spinātā. Moše bar Kēpā gišrā ʿabyā d-mettsim l-ʿel b-meṣʿat benyānē qārē gamlā, haw da-ʿlāw(hy) mettsimin qaysē (ʾ)ḥrānē men trayhon gabbāw(hy) w-taṭlilā d-a(y)k hākan gamlā metqrā. (ʾ)ḥrā[nē] dēn d-ʿal gamlā d-besrā w-da-kyānā rāmez wa-b-leššānā yawnāyā qamēlos metemar. (ʾ)ḥrā[nē] dēn āmrin d-gamlā haw d-emar māran b-ewangelyon sgidā — da-dlil (h)u l-gamlā l-meʿal ba-ḥrurā da-mḥaṭṭā — l-hānā gamlā d-ḥayy āmar, w-law d-a(y)k (ʾ)ḥrā[nē] šāṭrin l-gamlā. ba-ṣḥāḥā (ʾ)nāšin dēn āmrin d-šawšmāna (h)w arik reglē w-lā šarririn. w-gamlā b-meṣʿat ḥaywātā dakyātā w-ṭaʾmātā itāw(hy), b-hāy gēr d-metgawrar, men ḥaywātā dakyātā metḥšeb, wa-b-hāy d-lā ṣāryā parstēh, men ṭaʾmātā.

A gamlā is also a rope [Arabic]. In one copy: Cyril calls the thick rope with which people tie their ships a gamlā. Moše bar Kēpā calls the thick beam people place at the top of buildings in the middle a gamlā, the one on which other pieces of wood are placed from either side, and a ceiling like this is called a gamlā. Others [say] that it means the natural animal [? lit. of flesh and of nature] gamlā (camel), and in Greek it is called kámēlos. Others say that the gamlā that the Lord mentioned in the Gospel — i.e., “it is easier for a gamlā to enter the eye of a needle” — by this he means a living gamlā, and not, as some foolishly say, a [non-living] gamlā [i.e. a rope, as in the interp. above?]. In one copy: Some people say that it is an ant with long, unstable legs. A camel is midway between the categories of clean and unclean animals: since it chews the cud, it is counted among clean animals, and since it does not split the hoof, among unclean.

[NB with this ant mentioned here cf. Brockelmann, Lexicon Syriacum, 2d ed., 120b (s.v. gamlā mng. 2c), JBA gamlānāʾāh (Sokoloff, Dict. Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, 289-290); also Persian uštur mūr (camel-ant).]

The Gospel verses in Greek, Armenian, and Georgian

(English translations in the next section.)

Mt 19:24

πάλιν δὲ λέγω ὑμῖν, εὐκοπώτερόν ἐστιν κάμηλον διὰ τρυπήματος ῥαφίδος διελθεῖν ἢ πλούσιον εἰσελθεῖν εἰς τὴν βασιλείαν τοῦ θεοῦ.

Դարձեալ ասեմ ձեզ· դիւրի́ն է մալխոյ մտանել ընդ ծակ ասղան. քան մեծատան յարքայութիւն ա՟յ մտանել։

դիւրին easy, light | մալուխ, -լխոյ rope (supposedly also “camel”; see note below) | ծակ, -ուց hole | ասեղն, ասղան, -ղունք, -ղանց needle | մեծատուն, մեծատան, -անց rich NB on մալուխ, see Lagarde, Armenische Studien, № 1404; Ačaṙean, 3.226-227; Künzle 2.437 says “Die Bedeutung ‘Kamel’ ist wohl durch diese NT-Stellen irrtümlich in die armen. Lexika eingegangen.” The proper Arm. word for camel is ուղտ, Lagarde, Arm. St., № 1760 (cf. MP uštar, NP uštur; Sanskrit उष्ट्र uṣṭra).

A89 ႾႭჃႠႣႥႨႪჁႱ ႠႰႱ ႬႠႥႨႱႠ ႫႠႬႵႠႬႨႱႠ ႱႠႡႤႪႨ ჄႭჃႰႤႪႱႠ ႬႤႫႱႨႱႠႱႠ ႢႠႬႱႪႥႠႣ Ⴅ~Ⴄ . . . . . . . ႸႤႱႪႥႠႣ ႱႠႱႭჃႴႤႥႤႪႱႠ Ⴖ~ႧႨႱႠႱႠ

ხოჳადვილჱს არს ნავისა მანქანისა საბელი ჴოჳრელსა ნემსისასა განსლვად ვ(იდრ)ე . . . . . . . შესლვ[ა]დ სასოჳფეველსა ღ(მრ)თისასა

ხ-ოჳ-ადვილ-ჱს easier (< ადვილი easy) | ნავი ship | მანქანაჲ mechanism, machine | საბელი cable, rope, cord | ჴურელი hole | ნემსი needle

Ad მერმე გეტყჳ თქუენ: უადვილესა ზომთსაბლისაჲ ჴურელსა ნემსისასა განსლვაჲ, ვიდრე მდიდრისაჲ შესლვად სასუფეველსა ღმრთისასა.

უადვილეს easier (< ადვილი easy) | ზომთ(ა)-საბელი cable, thick rope (cf. Rayfield et al., 695a; ზომი measurement) | მდიდარი rich

PA და მერმე გეტყჳ თქუენ: უადვილეს არს მანქანისა საბელი განსლვად ჴურელსა ნემსისასა, ვიდრე მდიდარი შესლვად სასუფეველსა ღმრთისასა.

At და მერმე გეტყჳ თქუენ: უადვილეს არს აქლემი განსლვად ჴურელსა ნემსისასა, ვიდრე მდიდარი შესლვად სასუფეველსა ცათასა.

აქლემი camel

Mk 10:25

εὐκοπώτερόν ἐστιν κάμηλον διὰ [τῆς] τρυμαλιᾶς [τῆς] ῥαφίδος διελθεῖν ἢ πλούσιον εἰς τὴν βασιλείαν τοῦ θεοῦ εἰσελθεῖν.

դիւրի́ն է մալխոյ ընդ ծակ ասղան անցանել. քան մեծատան յարքայութիւն ա՟յ մտանել։.

անցանեմ, անցի to pass, flow, run

Ad უადვილეს არს ზომსაბელისა განსლვაჲ ჴურელსა ნემსისა, ვიდრეღა <არა> [?] მდიდარი სასუფეველსა ღმრთისასა შესულად.

PA უადვილჱს არს მანქანისა საბელი ჴურელსა ნემსისასა განსლვად, ვიდრე მდიდარი სასუფეველსა ღმრთისასა შესლვად.

At უადვილეს არს აქლემი ჴურელსა ნემსისასა განსლვად, ვიდრე მდიდარი შესლვად სასუფეველსა ღმრთისასა.

Lk 18:25

εὐκοπώτερον γάρ ἐστιν κάμηλον διὰ τρήματος βελόνης εἰσελθεῖν ἢ πλούσιον εἰς τὴν βασιλείαν τοῦ θεοῦ εἰσελθεῖν.

դիւրագոյն իցէ մալխոյ ընդ ծակ ասղան անցանել. քան մեծատան յարքայութիւն ա՟յ մտանել։.

դիւրագոյն easier

A89 ႾႭჃႠႣႥႨႪჁႱ ႠႰႱ ႫႠႬႵႠႬႨႱ ႱႠႡႤႪႨ ჄႭჃႰႤႪႱႠ ႬႤႫ ႱႨႱႠႱႠ ႢႠႬႱႪႥႠႣ Ⴅ~Ⴄ ႫႣႨႣႠႰႨ ႱႠႱႭჃႴႤႥႤႪႱႠ Ⴖ~ႧႨႱႠႱႠ

ხოჳადვილჱს არს მანქანის საბელი ჴოჳრელსა ნემსისასა განსლვად ვ(იდრ)ე მდიდარი სასოჳფეველსა ღ(მრ)თისასა

Ad უადვილეს არს მანქანისსაბელი ჴურელსა ნემსისასა განსლვად, ვიდრე მდიდარი სასუფეველსა ღმრთისასა შესლვად.

PA = Ad

At უადვილეს არს მანქანისა საბელი ჴურელსა ნემსისასა განსლვად, ვიდრე მდიდარი შესლვად სასუფეველსა ღმრთისასა.

English translations of these verses

Mt 19:24

Arm Again I say to you: it is easier for a rope to enter the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter the kingdom of God.

A89 It is easier for a rope from a ship’s apparatus to go through the eye of a needle than [for the rich] to enter the kingdom of God.

Ad Again I say to you: It is easier for a cable to go through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter the kingdom of God.

PA And again I say to you: It is easier for the rope of an apparatus to go through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter the kingdom of God.

At And again I say to you: It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter the kingdom of heaven. [sic! Not “of God”]

Mk 10:25

Arm It is easier for a rope to pass through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter the kingdom of God.

Ad It is easier for a cable to go through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter the kingdom of God.

PA It is easier for the rope of an apparatus to go through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter the kingdom of God.

At It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter the kingdom of God.

Lk 18:25

Arm It would be easier for a rope to pass through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter the kingdom of God.

A89 It is easier for the rope of an apparatus to go through the eye of a needle than for the rich [to enter] the kingdom of God.

Ad It is easier for the rope of an apparatus to go through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter the kingdom of God.

PA = Ad

At ≈ Ad

Conclusion

So here is how the witnesses stand:

|

Camel |

Rope |

| Greek |

✓ |

|

| Some Greek exeg. |

|

✓ |

| Armenian |

|

✓ |

| Syriac |

✓ |

|

| Geo early, PA |

|

✓ |

| Geo Athonite |

✓ |

✓ (Lk only) |

For Greek, I wonder about the real existence of the word κάμιλος (with iota, not ēta, but both words pronounced the same at this period). I don’t know that it is attested anywhere that is certainly unrelated to the Gospel passages. More generally, is there an explanation for the two opposed readings “camel” and “rope”? There is in Arabic a similarity between ǧamal (camel) and ǧuml/ǧumla (“thick rope”, see Lane 460), but it is treading on thin ice to have recourse to this similarity as an explanation for earlier texts with no palpable connection to Arabic. It may simply be the case that, as Cyril says, in nautical argot ropes went by the name “camels”. (And we should remember that there were sailors in Jesus’ circle.)

The earliest reading may well have been “camel”, but a change to “rope” does not really make for an easier reading: one can put a thread through a needle’s eye, but a rope will go through it no more than a camel will! In any case, some traditions clearly side with “rope”, such that those traditions’ commonest readers and hearers of the Gospel passage would have known nothing of a camel passing through the eye of a needle, only a rope, and apparently one large enough to handle marine functions!

There is no early evidence among the sources above for “camel” in Georgian (or Armenian), while Greek knows both, as does Syriac (via Greek sources, to be sure). This variety of readings, attested without a doubt, adds to the richness of the textual witness of the Bible and the history of its interpretation. There are probably further exegetical and lexical places in Greek, Syriac, Armenian, and Georgian that bear on this question of what we’re dealing with here, a camel or a rope, but this is, I hope, at least an initial basis for some future work on the question for anyone interested.

I learned earlier this week from a tweet by Matthew Crawford (@mattrcrawford) that the Rabbula Gospels are freely available to view online in fairly high-quality images. This sixth-century manuscript (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 1.56) is famous especially for its artwork at the beginning of the codex before, surrounding, and following the Eusebian canon tables, including both figures from biblical history and animals: prophets, Mary, Jesus, scenes from the Gospels (Judas is hanging from a tree on f. 12r), the evangelists, birds, deer, rabbits, &c. Beginning on f. 13r, the folios are strictly pictures, the canon tables having been completed. These paintings are very pleasing, but lovers of Syriac script have plenty to feast on, too. The main text itself is written in large Estrangela, with the colophon (f. 291v-292v) also in Estrangela but mostly of a much smaller size. Small notes about particular lections are often in small Serto. The manuscript also has several notes in Syriac, Arabic, and Garšūnī in various hands (see articles by Borbone and Mengozzi in the bibliography below). From f. 15v to f. 19r is an index lectionum in East Syriac script. The Gospel text itself begins on f. 20r with Mt 1:23 (that is, the very beginning of the Gospel is missing).

The images are found here. (The viewer is identical to the one that archive.org uses.)

Rabbula Gospels, f. 231r, from the story of Jesus’ turning the water into wine, Jn 2.

Rabbula Gospels, f. 5r. The servants filling the jugs with the water that will become wine.

For those interested in studying this important manuscript beyond examining these now accessible images, here are a few resources:

Bernabò, Massimò, ed. Il Tetravangelo di Rabbula: Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 1.56. L’illustrazione del Nuovo Testamento nella Siria del VI secolo. Folia picta 1. Rome, 2008. A review here.

Bernabò, Massimò, “Miniature e decorazione,” pp. 79-112 in Il Tetravangelo di Rabbula.

Bernabò, Massimò, “The Miniatures in the Rabbula Gospels: Postscripta to a Recent Book,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 68 (2014): 343-358. Available here.

Borbone, Pier Giorgio, “Codicologia, paleografia, aspetti storici,” pp. 23-58 in Il Tetravangelo di Rabbula. Available here.

Borbone, Pier Giorgio, “Il Codice di Rabbula e i suoi compagni. Su alcuni manoscritti siriaci della Biblioteca medicea laurenziana (Mss. Pluteo 1.12; Pluteo 1.40; Pluteo 1.58),” Egitto e Vicino Oriente 32 (2009): 245-253. Available here.

Borbone, Pier Giorgio, “L’itinéraire du “Codex de Rabbula” selon ses notes marginales,” pp. 169-180 in F. Briquel-Chatonnet and M. Debié, eds., Sur les pas des Araméens chrétiens. Mélanges offerts à Alain Desreumaux. Paris, 2010. Available here.

Botte, Bernard, “Note sur l’Évangéliaire de Rabbula,” Revue des sciences religieuses 36 (1962): 13-26.

Cecchelli, Carlo, Giuseppe Furlani, and Mario Salmi, eds. The Rabbula Gospels: Facsimile Edition of the Miniatures of the Syriac Manuscript Plut. I, 56 in the Medicaean-Laurentian Library. Monumenta occidentis 1. Olten and Lausanne, 1959.

Leroy, Jules, “L’auteur des miniatures du manuscrit syriaque de Florence, Plut. I, 56, Codex Rabulensis,” Comptes-rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Paris 98 (1954): 278-283.

Leroy, Jules, Les manuscrits syriaques à peintures, conservés dans les bibliothèques d’Europe et d’Orient. Contribution à l’étude de l’iconographie des églises de langue syriaque. Paris, 1964.

Macchiarella, Gianclaudio, “Ricerche sulla miniatura siriaca del VI sec. 1. Il codice. c.d. di Rabula,” Commentari NS 22 (1971): 107-123.

Mango, Marlia Mundell, “Where Was Beth Zagba?,” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 7 (1983): 405-430.

Mango, Marlia Mundell, “The Rabbula Gospels and Other Manuscripts Produced in the Late Antique Levant,” pp. 113-126 in Il Tetravangelo di Rabbula.

Mengozzi, Alessandro, “Le annotazioni in lingua araba sul codice di Rabbula,” pp. 59-66 in Il Tetravangelo di Rabbula.

Mengozzi, Alessandro, “The History of Garshuni as a Writing System: Evidence from the Rabbula Codex,” pp. 297-304 in F. M. Fales & G. F. Grassi, eds., CAMSEMUD 2007. Proceedings of the 13th Italian Meeting of Afro-Asiatic Linguistics, held in Udine, May 21st-24th, 2007. Padua, 2010.Available here.

Paykova, Aza Vladimirovna, “Четвероевангелие Раввулы (VI в.) как источник по истории раннехристианского искусства,” (The Rabbula Gospels (6th cent.) as a Source for the History of Early Christian Art) Палестинский сборник 29 [92] (1987): 118-127.

Rouwhorst, Gerard A.M., “The Liturgical Background of the Crucifixion and Resurrection Scene of the Syriac Gospel Codex of Rabbula: An Example of the Relatedness between Liturgy and Iconography,” pp. 225-238 in Steven Hawkes-Teeples, Bert Groen, and Stefanos Alexopoulos, eds., Studies on the Liturgies of the Christian East: Selected Papers of the Third International Congress of the Society of Oriental Liturgy Volos, May 26-30, 2010. Eastern Christian Studies 18. Leuven / Paris / Walpole, MA, 2013.

Sörries, Reiner, Christlich-antike Buchmalerei im Überblick. Wiesbaden, 1993.

van Rompay, Lucas, “‘Une faucille volante’: la représentation du prophète Zacharie dans le codex de Rabbula et la tradition syriaque,” pp. 343-354 in Kristoffel Demoen and Jeannine Vereecken, eds., La spiritualité de l’univers byzantin dans le verbe et l’image. Hommages offerts à Edmond Voordeckers à l’occasion de son éméritat. Instrumenta Patristica 30. Steenbrugis and Turnhout, 1997.

Wright, David H., “The Date and Arrangement of the Illustrations in the Rabbula Gospels,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 27 (1973): 199-208.

This time our Georgian lines come from Psalm 151 in a tenth-century Sinai manuscript. Among the following Georgian manuscripts of the Psalms in the old Sinai collection, only № 42 (see Garitte, Catalogue, pp. 156-158) has Psalm 151 (ff. 257v-258r, image 263), there following the Odes and the Beatitudes:

- 22 (10th/11th, nusxuri)

- 29 (10th, asomtavruli)

- 42 (10th, asomtavruli)

- 86 (14th/15th, nusxuri)

The others listed here only have the 150 Psalms and the Odes, except for № 22, which is incomplete at the end, and so it is not known what it had in addition to the 150 Psalms. Ps 151 not in the Graz manuscript, which ends with the Odes, but it is in Red. A, ed. M. Shanidze (at TITUS here).

Here is an image of our verse from the aforementioned Sinai manuscript (thanks to E-corpus):

Ps 151:7 in Sinai geo. 42, f. 258r

Here is the asomtavruli and a transliteration into mxedruli:

Ⴞ(ႭႪႭ) ႫႤ ႱႠႾႤႪႨႧႠ ႳႴႪႨႱႠ Ⴖ(ႫႰ)ႧႨႱႠ ႹႤႫႨႱႠჂႧႠ ႫႭႥႨႶႤ ႫႠႾჃႪႨ ႨႢႨ ႫႨႱႨ ႣႠ ႫႭႥჀႩႭჃႤႧႤ ႧႠႥႨ ႫႨႱႨ ႣႠ ႠႶႥჄႭႺႤ ႷႭჃႤႣႰႤႡႠჂ ႻႤႧႠ ႢႠႬ Ⴈ(ႱႰႠ)ჁႪႨႱႠႧႠ

ხ(ოლო) მე სახელითა უფლისა ღ(მრ)თისა ჩემისაჲთა მოვიღე მახჳლი იგი მისი და მოვჰკუეთე თავი მისი და აღვჴოცე ყოჳედრებაჲ ძეთაგან ი(სრა)ჱლისათა.

- მო-ვ-ი-ღე aor 1sg მოღება to take, get

- მახჳლი sword

- მო-ვ-ჰ-კუეთ-ე aor 1sg O3 მოკუეთა to cut off

- აღ-ვ-ჴოც-ე aor 1sg აღჴოცა to destroy, remove

- ყუედრებაჲ reproach, derision, abuse

Finally, for comparison, here is the verse in Greek, Armenian, and Syriac. The Georgian text is unique in having “with the name of the Lord, my God” at the beginning of the verse. (Syriac from Harry F. van Rooy, “A Second Version of the Syriac Psalm 151,” Old Testament Essays 11:3 (1998): 567-581; see also William Wright, “Some Apocryphal Psalms in Syriac,” Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology 9 (1886-1887): 257-266.)

ἐγὼ δὲ σπασάμενος τὴν παρ᾽ αὐτοῦ μάχαιραν ἀπεκεφάλισα αὐτὸν καὶ ἦρα ὄνειδος ἐξ υἱῶν Ισραηλ.

Ես հանի զսուսեր ՛ի նմանէ եւ հատի́ զգլուխ նորին, եւ բարձի զնախատինս յորդւոցն ի(սրաէ)լի։

հանեմ, հանի to draw, pull out | սուսեր sword | հատանեմ, հատի to cut | բառնամ, բարձի to lift, remove | նախատինք injury, blame, reproach, dishonor

9SH1 enā dēn kad šemṭēt saypēh pesqēt rēšēh w-arimēt ḥesdā men bnayyā d-Isrāʾēl

šmṭ to draw | saypā sword | psq to cut | rwm C to lift, remove | ḥesdā shame

12t5 enā dēn šemṭēt menēh ḥarbēh w-bēh nesbēt rēšēh w-aʿbrēt ḥesdā men Isrāʾēl

ḥarbā sword | nsb to take | ʿbr C to remove

In Sarjveladze-Fähnrich, 960a, s.v. რაკა (and 1167b, s.v. უთჳსესი), the following line is cited from manuscript A-689 (13th cent.), f. 69v, lines 20-23:

This is a question-and-answer kind of commentary note on the word raka in Mt 5:22. There is probably something analogous in Greek or other scholia, but I have not checked. For this word in Syriac and Jewish Aramaic dialects, see Payne Smith 3973-3974; Brockelmann, LS 1488; DJPA 529b; and for JBA rēqā, DJBA 1078a (only one place cited, no quotation given). For the native lexica, see Bar Bahlul 1915 and the quotations given in Payne Smith.

For this word in this verse, the Syriac versions (S, C, P, H) all have raqqā, Armenian has յիմար (senseless, crazy, silly), and in the Georgian versions, the earlier translations have შესულებულ, but the later, more hellenizing translations have the Aramaic > Greek word რაკა on which the scholion was written. Before returning to the Georgian scholion above, let’s first have a look at parts of this verse in Greek and all of these languages. Note this Georgian vocabulary for below:

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

So now we return to the scholion given above.

კითხვაჲ: რაჲ არს რაკა? მიგებაჲ: სიტყუაჲ სოფლიოჲ, უმშჳდესადრე საგინებელად უთჳსესთა მიმართ მოპოვნებული

Finally, here is an English translation of the scholion:

That is, according to the scholiast there are harsher, stronger vocatives with which to berate someone, but when just a little verbal aggression is needed, raka is the word to choose!

Share this: