Archive for the ‘Church of the Forty Martyrs’ Category

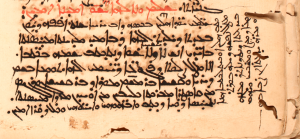

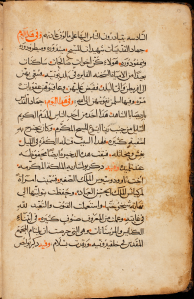

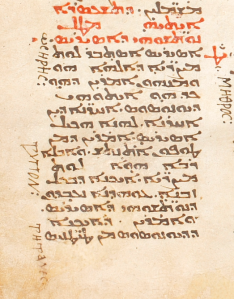

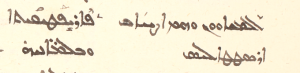

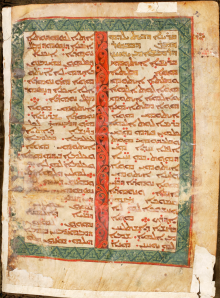

CFMM 259, p. 195

This image is of the beginning of Isaac (of Antioch)’s “Homily (Memra) on the Departure (Death) of Children”. The memra begins:

O how bitter is the departure,

How hard and bitter the separation,

That separates a mother from her children,

And a bearer from her beloved ones.

With what voices can we mourn

A beloved, beautiful child,

Who sprouted and grew like a flower,

But quickly withered and vanished?

Most Syriac poets, even Jacob of Sarug, have generally been overshadowed by Ephrem, but lines like these, poignant and emotive, serve as a reminder that there are riches beyond those of Ephrem. (I thought the same recently while reading Qurillona.)

Notice of this homily is recorded in Bickell’s list of incipits (no. 6; in vol. 1 of his ed. of Isaac’s homilies), and according to Sebastian Brock’s list of Isaac’s homilies (JSS 32 [1987]: 279-313), this one is unpublished. There is, however, another memra that begins similarly (no. 177 in Bickell’s list, also included in Brock’s) and that has been published: P. Zingerle, Chrestomathia Syriaca, pp. 387–394 (from Vat. Syr. 92).[1] It turns out that the memra from CFMM 259 above, a text thought to have been unpublished, is in fact not a separate memra from that published in Zingerle’s chrestomathy; it is another version of it with different wording here and there. A comparison even of the short sample given above with the text that Zingerle published shows some of these differences, and there are more. I am not (now, at least) making a full collation, but I note that the reading of CFMM 259 has bearing on Zingerle’s remark on p. 387 about d-pāršā in his text. We are, of course, not unused to the fact of different textual versions, but it is all the easier to get thrown off by the fact when different wording occurs immediately at the beginning of a text!

The manuscript is dated 2220 AG (= 1908/9 CE), and there is a donation note at the beginning dated 1948. A table of contents is supplied at the beginning, but it missed a few of the texts in the manuscript, of which there is a total of thirty. In addition to providing another witness to this homily of Isaac’s, it also contains a number of other notable texts, homiletic, hagiographic (some of which are from Palladios), and apocryphal. Among them:

- Memra on the Cream of Wisdom by John of Manʿim (cf. Barsoum, Scattered Pearls, p. 521)

- The Revelations of the Twelve Apostles, translated from Hebrew into Greek and Greek into Syriac

- The Two Letters that Fell from Heaven (see generally GCAL I 295-296)

- The Story of Sergius Baḥira (text and trans. in B. Roggema, The legend of Sergius Baḥīrā: eastern Christian apologetics and apocalyptic in response to Islam [Brill, 2009].)

- The Story of Maurice the Believing Emperor

- The Story of Taḥsia, the Prostitute that Anba Bessarion Instructed (cf. Bedjan, AMS VII 105-109; also BHO 1137 for Armenian?)

- The Story of Honorios the Emperor

- The Story of Moses the Ethiopian (cf. Bedjan, AMS VII 219-224)

- Memra on Himself, by Bar Qiqi (cf. Scattered Pearls, p. 414)

- The Story of Simeon of the Olives

- The Story of Daniel of Scetis (This text does not seem to exactly match any of those translated by S.P. Brock in T. Vivian, ed., Witness to Holiness: Abba Daniel of Scetis, pp. 181-205.)

- The Story of Daniel of Galaš

- The Story of Mark of Jabal Tarmaq

- Sogitha (dialogue poem) on Joseph and Benjamin (cf. S.P. Brock, Sogyata Mgabbyata [1982], pp. 15-17; cf. Le Muséon 97 (1984): 42.)[2]

The few bibliographic references above are not complete. Some of these texts exist also in other copies at HMML (and elsewhere), either in Syriac or Arabic / Garšūnī.

Notes

[1] Thanks to those members of the Hugoye list who shared copies of Zingerle’s book with me.

[2] Thanks to Kristian Heal for pointing out to me these references for the sogitha.

HMML’s partnership with Saint Mark’s Monastery, Jerusalem, to digitize their manuscript collection has yielded high-quality digital images of close to 300 manuscripts. A hard drive of the latest files arrived here last week and they have been uploaded to the server. The collection was cataloged in the early numbers of Oriens Christianus by G. Graf, A. Baumstark, and Ad. Rücker, and in the late 1980s thirty-one manuscripts from this collection were microfilmed by BYU and cataloged by William Macomber; scans of these microfilms have been graciously made available at the CPART site. Until the collection is again examined closely, it will not be certain how much the Saint Mark’s collection has changed from these earlier efforts at scrutiny and description, i.e. which manuscripts have been lost, and which have been gained.

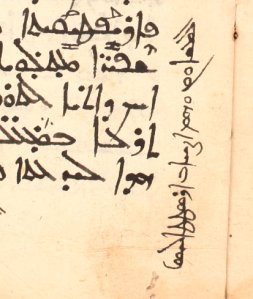

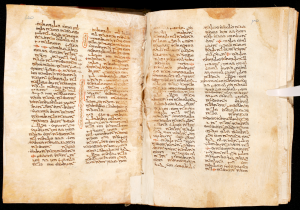

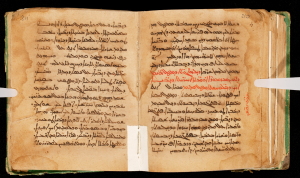

SMMJ 232, f. 148v

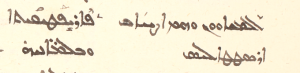

As is relatively well known thanks to the work of the earlier German scholars and of BYU and Macomber, the Saint Mark’s collection has several notable manuscripts. I hope that I will be able to adequately highlight some of these in the future here, but today I share with you a bit of information (and images) of two manuscripts of Bar ˤEbrāyā’s philosophical work, each copy containing his Tēgrat Tēgrātā (The Treatise of Treatises), Ktābā da-Swād Sofia (The Conversation of Wisdom), and Ktābā d-Bābātā (The Pupils [of the Eye]). The manuscripts are numbered 231 and 232, with 232 being the older and dated 1878 AG (= 1566/7 CE) on f. 196r, but dated to the month of Āb (August) in 1885 AG (1574) on f. 148v; see the image to the right. The scribe of this is Tomā bar Murād bar Giwargis of Klibin, near Mardin, and “my teacher and our teacher Tomā” is named in the colophon on f. 197r, that part copied earlier is the work of another scribe. Completion dates this divergent for parts of one manuscript are not hard to fathom when we realize that they were apparently first not of the same manuscript. Near the beginning of The Book of the Pupils, ff. 163-172 are marked as the second quire (the first not explicitly marked), while the first text in the whole manuscript, The Treatise of Treatises, takes up sixteen quires, which are marked, itself. It seems that up to f. 152 was originally separate from the rest of the book, and the two parts were later joined together. The later manuscript is dated on f. 308r to Tāmuz (July) 9, 1882, and it was most probably copied from no. 232. It, too, begins with The Treatise of Treatises, which was copied (up to f. 139) in the way of some other works of Bar ˤEbrāyā’s, with Syriac and Arabic (Garšūnī) having been copied side-by-side, but here there is no full Arabic version of The Treatise, only select words and sentences. Some — probably most or all, but I have not studied the copies closely — of these translated bits also appear in the sixteenth-century manuscript, but they do not there have such a broad space; they are merely written in the margins. Images of corresponding parts near the beginning of the work are below, with the comments explaining in Arabic what “Peripatetic” means.

SMMJ 232, f. 2r

SMMJ 231, f. 9v

Note

Abundant bibliographic and manuscript information on all three of these works by Bar ˤEbrāyā will be found in H. Takahashi, Barhebraeus: A Bio-Bibliography (Piscataway, 2005), 254-265, to which I would make the following additions based on my work in the Church of the Forty Martyrs collection:

- The Conversation of Wisdom

- CFMM 548, dated 1891, has Syriac and Garšūnī versions of the work.

- CFMM 546, dated 1879 and copied in Edessa.

- CFMM 547, dated 1923 and also copied in Edessa.

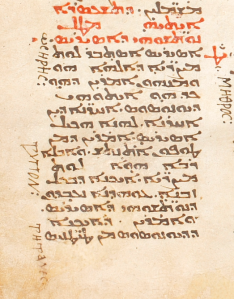

In a previous post[1] I highlighted the writing of someone’s name upside down to curse their memory. Another way is the deliberate alteration of someone’s name. Here is an example from CFMM 256: a short piece on Barṣawmā, bishop of Nisibis, (not to be confused with the roughly contemporaneous Syriac Orthodox monk Barṣawmā, whose many miracles are delineated in a lengthy text at the end of this very manuscript; see here).

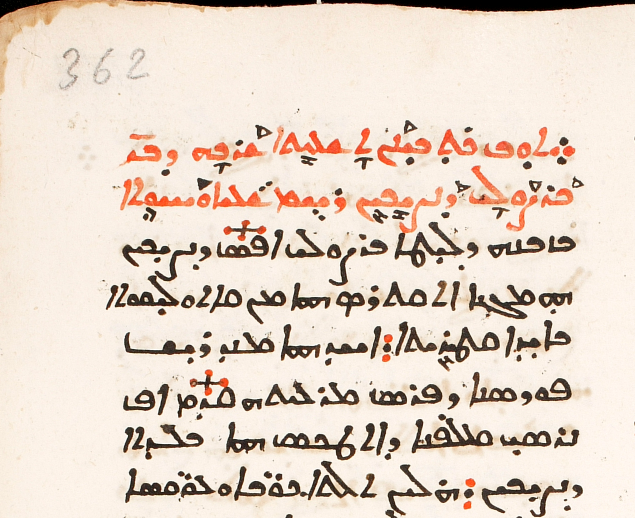

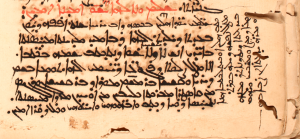

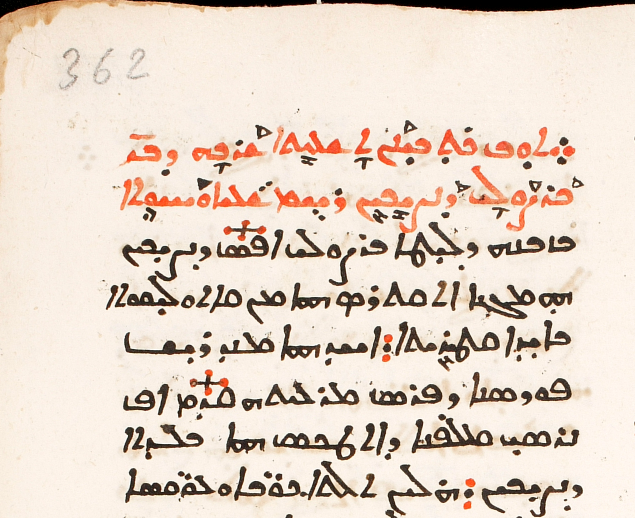

CFMM 256, p. 362

In the manuscript, this work logically follows the preceding one, which is on Nestorios.

This is not the first time the distortion of Barṣawmā’s name has been noted. Stephen Gero collects the known evidence in his Barṣawma of Nisibis and Persian Christianity in the Fifth Century, CSCO 426 (Louvain, 1981), 25-26 n. 4. One distortion that occurs in west Syriac manuscripts is BarṢWL’ (= -ṣulā, -ṣulē, -ṣawlā, -ṣawlē?), which Gero cites from Bar ˤEbrāyā’s Chronicon Ecclesiasticum.[2] He points out, though, that this word form (he does not posit either of the two forms with the diphthong, which is how the example above is vocalized) makes little sense as it is, since it does not mean anything in Syriac. He offers as its origin the word ṣulāyā, which he claims means”perversion (of justice)”, a meaning apparently taken from the English Payne Smith (p. 475), but notably, the big Payne Smith (col. 3401) calls this word, for which only two occurrences seem to be known, a “vox incerta”![3] The appeal to Arabic ṣawla, which in any case does not always have negative connotations, does not strike me as well-founded. Could it be that the purposefully distorted name is simply that, a distorted form without actual semantic weight on its own? That is, the last syllable has been changed from -mā to -lā, -li, or -le, and we should give up looking for some proper meaning in a word with the consonants ṢWLY (as in this manuscript) or ṢWL’ (as in the passage from the Chronicon Ecclesiasticum)? Is it also not without significance that the handwritten combination of the Syriac letters WL, if the L is slightly short, is very close in appearance to M, which is the correct letter in the regular form of Barṣawmā’s name?

This form of the name (with -Y), as noted, too, by Gero, occurs also in Philoxenos’ “Letter to Abū Yaˤfūr”, at least in Paul Harb’s edition,[4] and apparently also in Mingana’s partial edition, which I do not have immediate access to. Harb remarks on the word,

Il s’agit, à notre sens, d’une calligraphie spéciale du nom de Barsauma, que les Jacobites avaient l’habitude d’employer pour marquer leur mépris ou leur désapprobation envers lui. On sait qu’ils conservent jusqu’à nos jours l’habitude d’écrire le nom de Satan à l’envers. D’ailleurs cette façon d’écrire le nom du Barsauma nestorien leur permettait de le distinguer de leur Saint Barsauma.

Vööbus once[5] referred offhand in a list of “vitae which no scholar has seen” to a “Bar Sūlā of Nisibis”. It is hard to imagine that the Estonian scholar would not have recognized this short text on Barṣawmā in CFMM 256 — and it is certain that he saw this manuscript; see this previous post — for being what it is, but the name he cites and the one used in the manuscript are strikingly close. I do not otherwise know the text discussed here, but it may be an extract from a larger work; I welcome any further information on it which the incipit given here may bring to mind to readers.

Finally, some relevant sociolinguistic discussion on names and naming will be found in chapter 2 (particularly the earlier parts) of Keith Allan and Kate Burridge’s excellent Euphemism & Dysphemism: Language Used as Shield and Weapon (New York, 1991), the rest of which is in many places good for an erudite laugh.

Notes

[1] Incidentally, from Gero’s note (cited later in this post) the following should be added to the bibliography given in the post on cursing upside down: G. Khoury-Sarkis in L’Orient syrien 12 (1967): 454 n. 89, as well as Harb’s note referred to later in this post.

[2] Ed. Lamy and Abbeloos. Gero only cites it as col. 71, line 22; it should be noted that this is in part II of the Chronicon, which is separately paginated from part I. The editors give the regular form of the name from two witnesses in the apparatus.

[3] Sokoloff, p. 1279, follows the root meaning and noun pattern and thus simply gives “inclining, bending”.

[4] See “Lettre de Philoxène de Mabbūg au Phylarque Abū Ya‘fūr de Hīrtā de Bētna‘mān (selon le manuscrit № 115 du fond patriarcal de Šarfet),” Melto 3 (1967): 183-222. The word in question occurs at 220, l. 16. I am told that a new edition of the letter is forthcoming. For the earlier partial edition, see Alphonse Mingana, “The Early Spread of Christianity in Central Asia and the Far East,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 9 (1925): 297-371.

[5] “Important Manuscript Discoveries in the Syrian Orient,” Symposium Syriacum 1976, OCA 206 (Rome, 1978), 16.

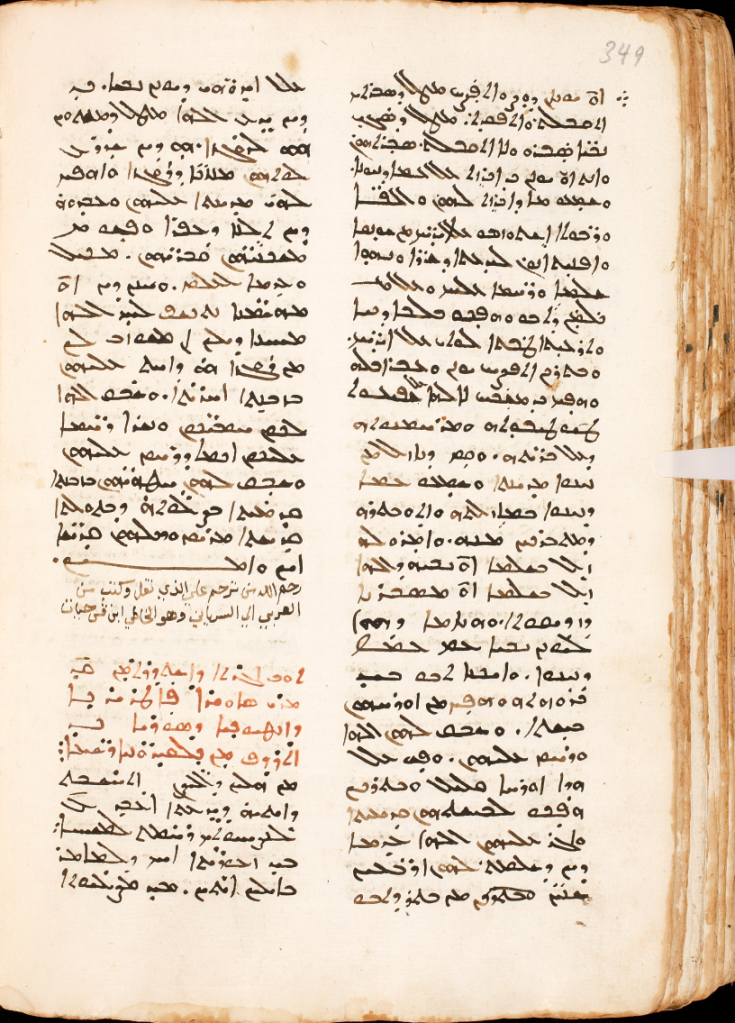

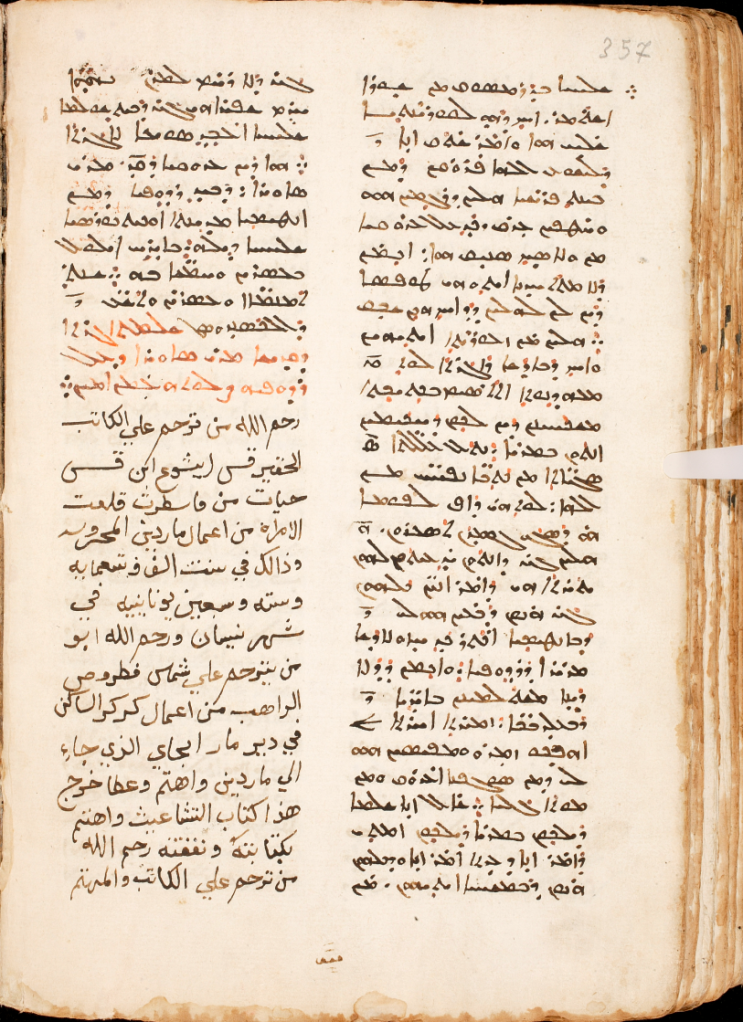

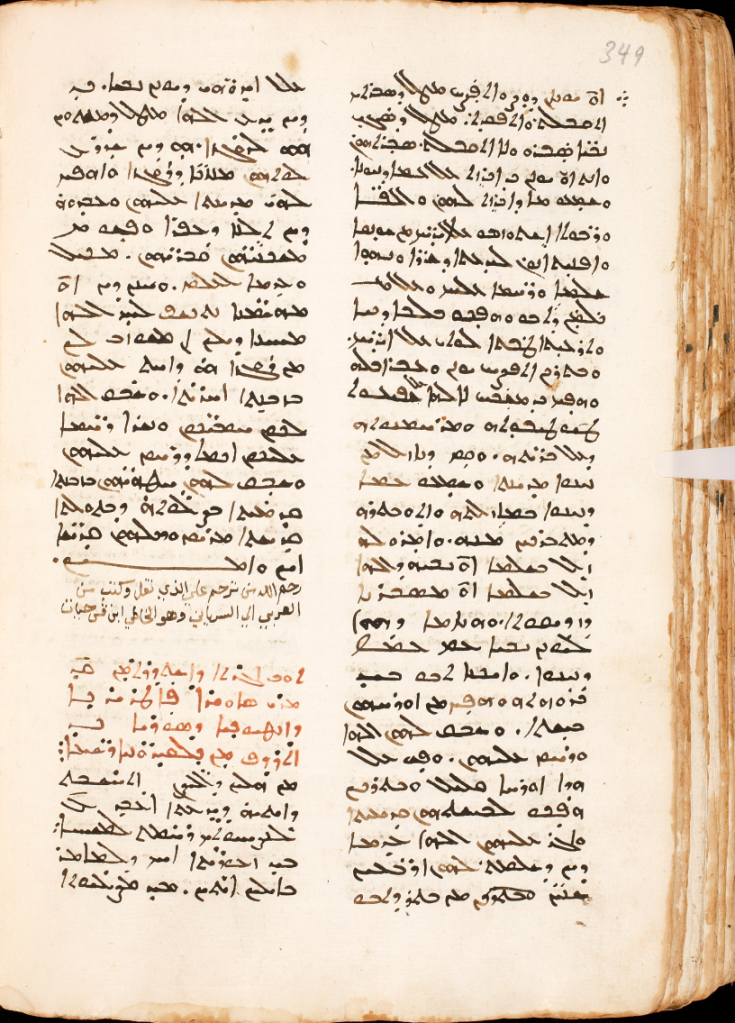

In a 17th-century manuscript made up mostly of hagiographic material (discussed briefly here) from the Church of the Forty Martyrs (Mardin, no. 256), I have come across a letter attributed to Severos of Antioch (d. 538), a well known figure in Syriac literature, especially to those interested in the theological literature of christological controversy. The letter is titled, The Letter Sent by Mar Severos, Patriarch of Antioch, when He Was Banished by the Wicked Chalcedonians. Severos wrote in Greek, in which language but little of his work survives, while a very notable corpus consisting of homilies, hymns, letters, and theological works survives in Syriac translation. Most of the letters surviving in Syriac — themselves still but a small part of Severos’ whole epistolary oeuvre of more than 3800 (!) letters — were published and translated by Brooks in the early twentieth century (see the bibliography). Arthur Vööbus in 1975 brought attention to another letter, the very one I have just met in the Mardin manuscript, two pages of which I supply below; Vööbus also points to a few other manuscripts with the letter (cf. plate 11 at the end of the Vööbus Festschrift, ed. R.H. Fischer [Chicago, 1977], for one from Damascus) and a brief discussion of the manuscript settings in which the letter has been transmitted. I point out this letter (and Vööbus’ article), not only because, as far as I know, the letter still remains unpublished and because of its uniqueness and significance, but also because subsequent scholarship on Severos seems to have taken little notice of it. Finally, it should be noted that there is an Arabic (Garšūnī) version of the letter in the big manuscript from Saint Mark’s Monastery, Jerusalem, no. 199 (ff. 524v-526v acc. to the foliation with Syriac letters); a scan of a microfilm of this manuscript — also chiefly of hagiographic content — is available here as SMC 3-2 and 3-3, but full-color images of the manuscript and the rest of the Saint Mark’s collection (about 300 mss) will soon be accessible through HMML.

Bibliography

Pauline Allen and C.T.R. Hayward, Severus of Antioch (London and New York, 2004).

S.P. Brock, “Severos of Antioch,” in Sebastian Brock, Aaron Butts, George Kiraz, and Lucas Van Rompay, eds., Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage (Piscataway, 2011).

——–, “Some New Letters of the Patriarch Severos,” in Studia Patristica XII (Berlin, 1975), pp. 17-24.

E.W. Brooks, A Collection of Letters of Severus of Antioch, PO 12.2 (1915) and 14.1 (1920).

——–, The Sixth Book of the Select Letters of Severus Patriarch of Antioch in the Syriac Version of Athanasius of Nisibis, 2 vols. (London, 1902-1904).

CPG III, nos. 7022-7081, esp. 7070.11.

A. Vööbus, “Découverte d’une lettre de Sévère d’Antioche,” Revue des études byzantines 33 (1975): 295-298. (Available here.)

CFMM 256, p. 349

CFMM 256, p. 357

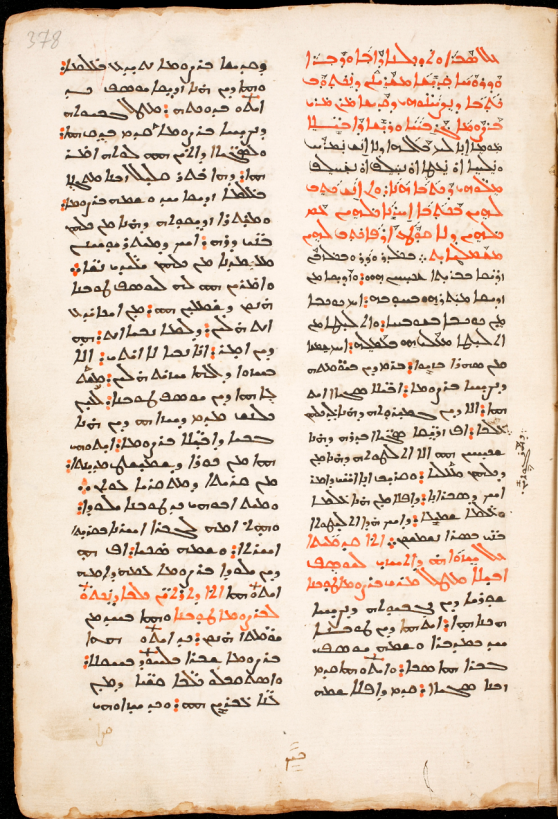

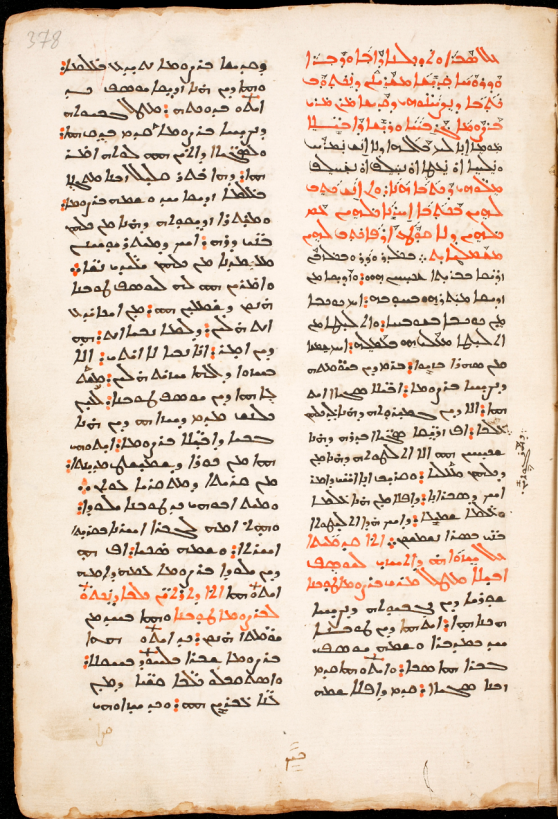

While the industrious François Nau published a summary, with Syriac excerpts and French translation, of the sixth-century Life of Barṣawmā (d. 458), the full text has, to my knowledge never been published. According to Nau (ROC 18 [1913] 272 n. 1), three Syriac copies of the work, all incomplete, are known to exist: BL Add. 12174, 14732, and 14734, and this information does not seem to have had cause for emendation in the intervening century. Now, however, a new witness to this long and interesting text can be added to the list: Church of the Forty Martyrs 256, pp. 378-477. The text comes almost at the end of a 500-page codex. The main hand is a distinct Serṭo that is very easy to read, and vowels are present here and there. The last page of the manuscript (513), which is written in a different hand than the majority of the book, has the date 1982 AG, that is, 1670/1 CE. This scribe says, “Don’t blame me because I messed it up, since the exemplar was in Arabic,” a statement that must refer to the text at the very end (on Moses), which the scribe apparently translated from Arabic into Syriac, and not to the Life of Barṣawmā. This copy of the Life of Barṣawmā is unfortunately missing a few folios at the end, but it goes to miracle no. 96 (out of 99 or 100). While of dubious historical value, the story most certainly possesses other qualities customarily met with in hagiographic literature, including just plain entertainment!

Bibliography

J.M. Fiey, Saints syriaques (Princeton, 2004), no. 79 (pp. 49-50).

F. Nau, “Résumé de monographies syriaques,” Revue de l’Orient chrétien 18 (1913): 270-276, 379-389; 19 (1914): 113-134, 278-289. (These and a host of other important articles are available here.)

L. Van Rompay, “Barṣawmo,” in Sebastian Brock, Aaron Butts, George Kiraz, and Lucas Van Rompay, eds., Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage (Piscataway, 2011).

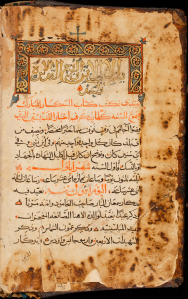

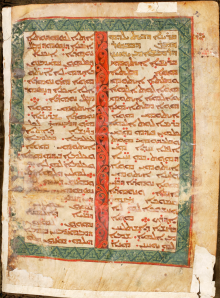

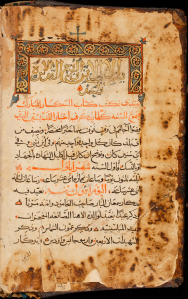

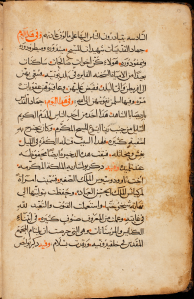

CFMM 251 is a beautiful copy of a synaxarion (the catalog of saints according to the day they are celebrated in the church) in Arabic. It follows the Greek menologion (text in PG 117) closely (but not exactly) and is almost complete, with only a folio or two missing at the end. Since the end is lacking, there is also no colophon, nor is there any clear indication of date elsewhere in the manuscript. The images below are the first page of the book, which begins with the month of Aylūl (= September), and p. 13, for Sept. 10, on which these saints are named: the sisters Menodora, Metrodora, and Nymphodora; Baripsibba; and Pulcheria.

CFMM 251, p. 1

CFMM 251, p. 13

Church of the Forty Martyrs (Mardin) manuscript no. 555, copied in 1963-64 by Malki Gülçe for Yuḥanon Dolabani at the Church of Mary in Elâzığ, contains the same texts in the same order as Mingana Syriac 559 (see Mingana’s Catalogue, vol. 1, cols. 1034-1039). This Mingana manuscript—a welcome break from the almost ubiquitous theology, liturgy, and the like—is well-known for containing Job of Edessa’s very interesting Book of Treasures, a facsimile of which was published with an English translation by Mingana himself in 1935. But this is not the only notable text in the manuscript; in addition, there is:

- a series of questions and answers attributed to Alexander Aphrodisias

- selected questions and answers from the books of Galen

- Job of Edessa’s short Treatise on Rabies (on which I have sent a proposal for this summer’s international Symposium Syriacum)

- a brief work attributed to Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq on the fact that there are four elements and not more or less

- a short text on dreams

- a short text on the heart and the brain attributed to a nameless monk

Mingana’s manuscript was copied for him in 1930 on the basis of an exemplar copied in 1532 AG (= 1220/21 CE). Another manuscript, also copied, it seems, from this 13th century manuscript, is Harvard Syr 132 (Goshen-Gottstein’s Catalogue, pp. 90-91).

The Mardin manuscript at the beginning, before the Alexander Aphrodisias text, has the end of a work (only one folio) that I have thus far not identified, a philosophical text that deals (at least in this fragment) with the soul. This work is completely unmentioned by Mingana and Goshen-Gottstein. While the Mardin manuscript is some decades younger than the Mingana or Harvard copies, there is neither clear evidence, nor, as far as I know, even likelihood, considering the time and place of its copying, that it was copied from either of these manuscripts rather than from the thirteenth-century exemplar itself, the colophonic parts of which are included in the Mardin copy, as in Mingana’s (I don’t know about the Harvard manuscript in this regard). Late manuscripts such as the Mardin copy, and even earlier ones, are known sometimes to derive from printed editions, but the only text in this group that has been published is the Book of Treasures, mentioned above. On a quick perusal of this newly identified manuscript, I observed that the text is often not always the same orthographically and lexically as the Mingana copy. Witness, for example, that the second adjective describing Alexander’s questions, both in the title and in the table of contents at the beginning of the volume, is not asyāyē “medical” (as in Mingana’s text), but usyāyē “essential”, which, it bears emphasizing, requires the writing of an extra letter in Syriac.

These questions of textual derivation would be moot if the thirteenth-century exemplar were discovered, and it may yet show up, perhaps even in one of the collections digitized or being digitized by HMML, but for the time being scholars interested in Syriac scientific and philosophical literature will welcome another witness thereto, even one as late as this one.

Church of the Forty Martyrs ms. 41, p. 46

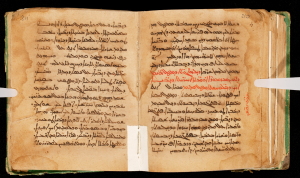

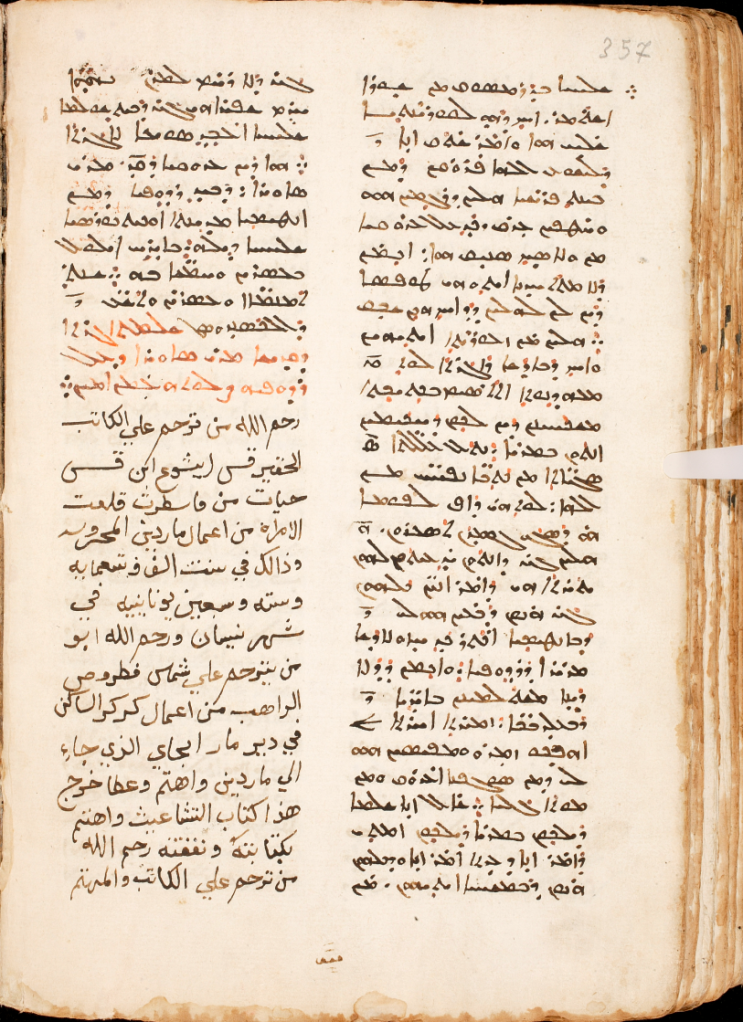

Below are the recto and verso of a folio (now pp. 31-32) from an undated (probably 13th century) Syriac Gospel Lectionary from the Church of the Forty Martyrs (formerly at Dayr Al-Zaˤfarān). The painting, one of twenty in this manuscript,[1] shows the birth of Jesus; it has has suffered somewhat in the middle of the page, and is thus not one of the better preserved, but is nevertheless fitting to current season of the church calendar. The Syriac text, from John 1,[2] is notable for the way in which it was written: outlined letters filled in with gold, and within a decorative border. A few other lections in the manuscript are also written this way, but the greater part is written in a fine, thick Esṭrangǝlā, an example of which I have also included.

Best wishes to all for year’s end and a new beginning!

[1] J. Leroy, Les manuscrits syriaques à peintures (Paris, 1964), vol. 1, pp. 371-383 (with some errors in reference to the manuscript’s pagination); vol. 2, pp. 127-136. I dare say these color images are rather more striking than the black and white reproductions in Leroy’s album. We can be thankful for the ease with which we can now reproduce such high-quality images.

[2] This reading, and most of the others, are of the Ḥarqlean version. Leroy says that the manuscript is Ḥarqlean, but there are in fact some lections from the Pǝšiṭtā, and they are so marked in the margins.

Church of the Forty Martyrs ms. 41, p. 31

Church of the Forty Martyrs, ms. 41, p. 32

ἅπανθ᾽ ὁ μακρὸς κἀναρίθμητος χρόνος

φύει τ᾽ ἄδηλα καὶ φανέντα κρύπτεται —Sophocles, Ajax 646-647 (Ajax speaking)

Just over a year ago a colleague wrote me asking about a certain Syriac manuscript to which he had seen a reference as belonging at Dayr Al-Zaˤfarān. I was cataloging the collection of this monastery at the time and the shelfmark in the reference he had found did not match at all anything I could find there, so after some further searching I gave him the news that for the present I was unsure about the manuscript’s whereabouts or even its survival. I knew, though, that a large number of the Dayr Al-Zaˤfarān manuscripts had made the short migration to the Church of the Forty Martyrs, in which collection the referenced shelfmark still did not match. I reported to my colleague that I would keep a close eye out for his manuscript when I started going through this large latter collection. Well, yesterday, one year and eleven days after my friend’s enquiry, my eyes fell upon the very manuscript he was looking for! I have happily reported the news to him.

Ajax says time both discloses and reveals: in this instance, at least, we can be glad of time’s revelatory march, and not it’s concealing power.

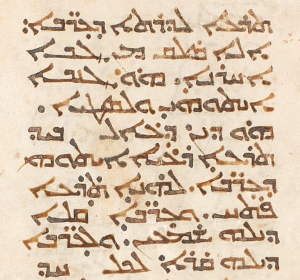

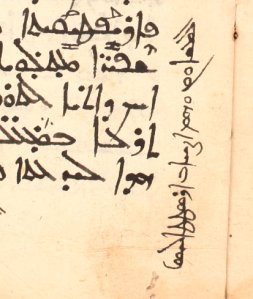

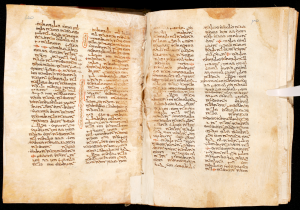

CFMM 158 (olim Zafaran 248), pp. 210-211

The beginning of scholion 19 (on Osiris)

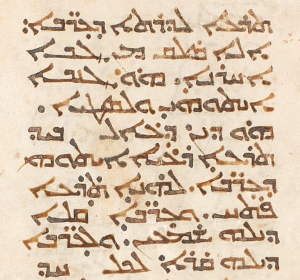

In my continuing work cataloging the Church of the Forty Martyrs (Mardin) manuscript collection, I came recently upon a fine old manuscript on parchment. Since most of what I have been reading lately is in Serṭo (West Syriac) script, the older Esṭrangela always immediately catches my attention. This particular manuscript is missing the beginning and ending folios, as well as several at various places in the middle, but as I quickly went through the surviving leaves to get an idea of its contents, I recognized something I thought I had seen before: part of the (very interesting!) mythological scholia to the orations of Gregory Nazianzen, which I studied some years ago in Sebastian Brock’s edition (Cambridge, 1971).[1] I pulled this edition off the shelf and looked at Brock’s discussion of the manuscripts he used and there indeed was a reference to a manuscript from Mardin (pp. 11-12; no shelfmark). He says that he used photographs “taken under somewhat adverse conditions, and a few readings are not entirely certain.” This text in the Mardin manuscript has many of the proper names of the scholia written in Greek, sometimes not quite correctly, in the margins, as can be seen in the image to the right (“Osiris”, “Typhon”, “Titans”; “Mithras” belongs to the scholion in the other column).

In addition to this work, which is missing one folio at the beginning, the Mardin manuscript, now no. 129, contains in part or in full orations nos. 18 (On his Father), 38 (On Epiphany, the Birth of Jesus), 39 (On the Lights), 41 (On the Holy Spirit), 27 (Against the Eunomians), 29 (On the Son, I), 30 (On the Son, II), and 31 (On the Holy Spirit, only one folio).[2] The manuscript is briefly described in Dolabani’s Dayr Al-Za`farān catalog (p. 22 in western numerals, but p. ܟܐ in Syriac!), so it was apparently there before having been relocated to the Church of the Forty Martyrs, like so many other manuscripts from the same monastery. After Dolabani (and Brock), there has been some doubt and uncertainty as to this important manuscript’s whereabouts:

Es steht nicht fest, ob die Handschrift überhaupt noch an ihrem ursprünglichen Aufenthaltsort in Mardin liegt, ob sie verlorengegangen ist, oder ob sie mit weiteren Manuskripten aus Mardin in eine andere Bibliothek verlegt wurde. (A.B. Schmidt and M. Quaschning-Kirsch in Le Muséon 113 [2000]: 90, n. 8.)

Le Centre d’études sur Grégoire de Nazianze n’a pas pu obtenir un microfilm de ce manuscrit dont on a, semble-t-il, perdu la trace. (J.-C. Haelewyck, CCSG 53, Corpus Nazianzenum 18 [2005], p. xii; cf. CCSG 65, Corpus Nazianzenum 23 [2007], p. xi.)

I am happy to report that the manuscript is not lost at all!

From Or. 29 (On the Son, I)

[1] Of more recent publications note especially J. Nimmo Smith, ed., Pseudo-Nonniani in IV Orationes Gregorii Nazianzeni Commentarii, with the assistance of S. Brock and B. Coulie (CCSG 27, Corpus Nazianzenum 2; Turnhout: Brepols, 1992), and Bernard Coulie, “Les versions orientales des commentaires mythologiques du Pseudo-Nonnos et la réception de la mythologie classique,” in Rosa Bianca Finazzi and Alfredo Valvo, eds., La diffusione dell’eredità classica nell’età tardoantica e medievale. Il Romanzo di Alessandro e altri scritti. Atti del seminario internazionale di studio (Roma-Napoli, 25-27 settembre 1997) (L’eredità classica nel mondo orientale 2; Alexandria : Edizioni dell’Orso, 1998), pp. 113-23.

[2] Syriac editions of some of these orations have been published in the CCSG, Corpus Nazianzenum series.