Archive for the ‘Syriac manuscripts’ Tag

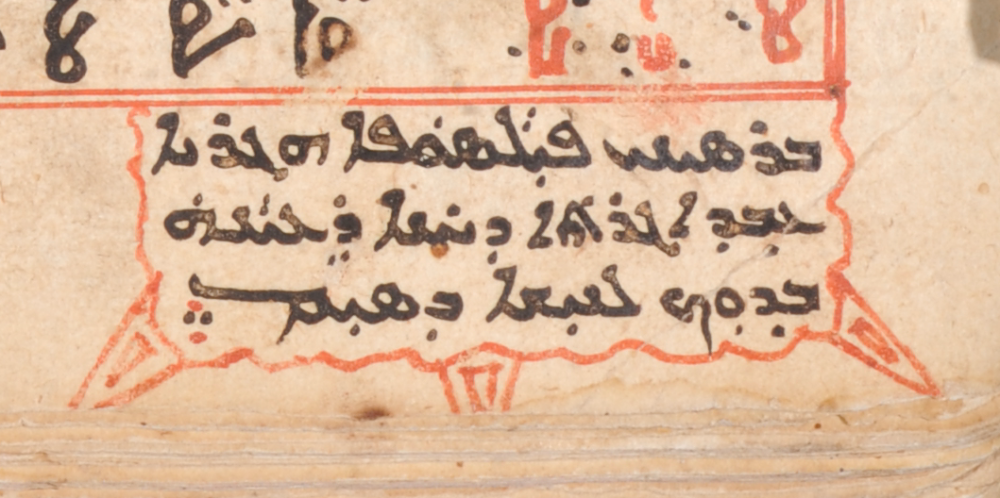

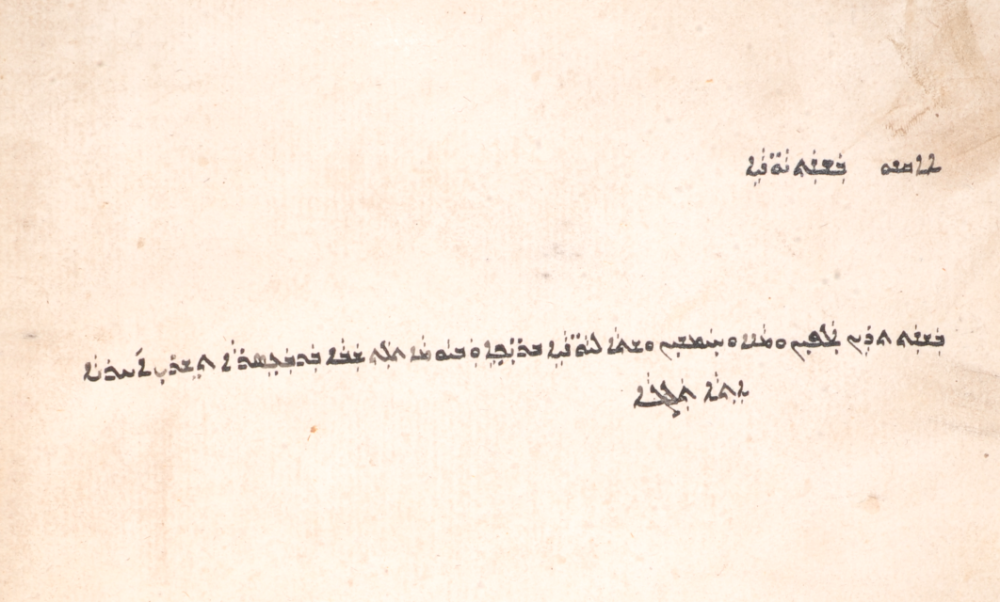

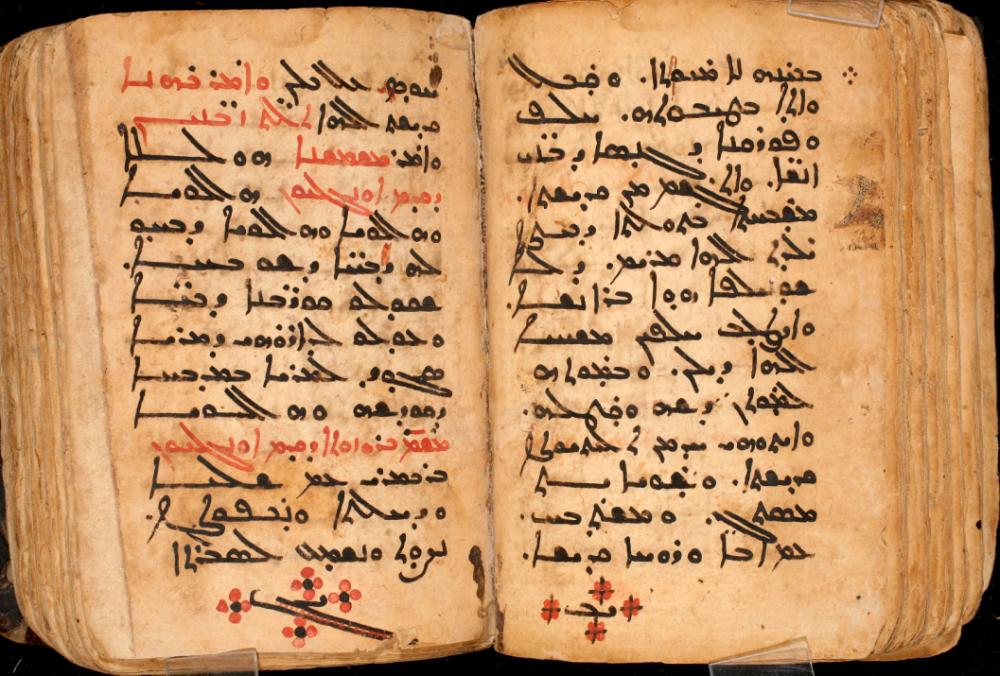

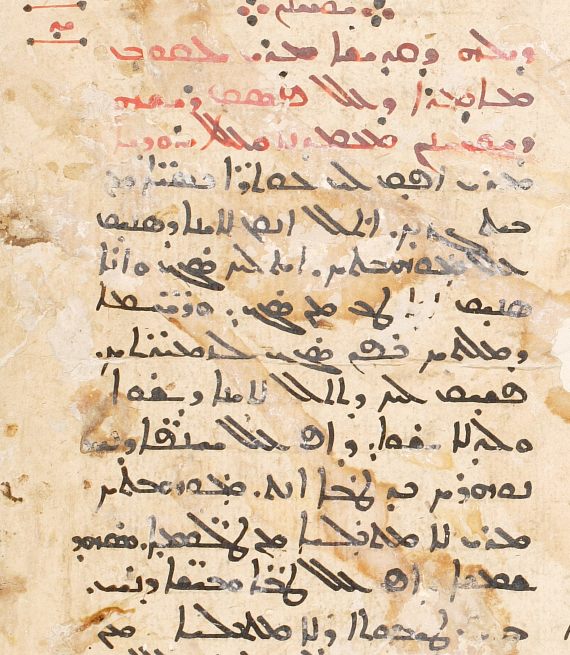

Ibn Sīnā (see also here, here, from the Enc. Iranica here, and specifically for metaphysics, here) stands among the most well known and most influential of philosophers who have written in Arabic, and his influence was hardly confined to the intellectual worlds where Arabic or Persian were the means of communication. From the twelfth and thirteenth centuries he was read in Latin — several volumes of the Latin witness to Ibn Sīnā have appeared since 1972 in editions by Simone van Riet (Brill) — and reflections of his work can be found in the writers of the Syriac Renaissance of the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries, especially in the voluminous work of Bar ʕebrāyā. Alongside the Qānūn fī ‘l-ṭibb may be mentioned especially his encyclopedic Kitāb al-šifāʔ, Dāneš-nāma (or Dānišnāma-i ʕalāʔī, in Persian, for the prince ʕalāʔ al-Dawla see here), and the Kitāb al-išārāt wa-‘l-tanbīhāt; the last mentioned work was translated into Syriac by Bar ʕebrāyā and there are two late copies with parallel Garšūnī and Syriac available at HMML: CFMM 550 and MGMT 20 (both twentieth century). John bar Maʕdani (d. 1263), a contemporary of Bar ʕebrāyā, penned two poems on the soul, one (or both) of which goes by the name of “The Bird” (pāraḥtā). I have recently cataloged an East Syriac manuscript of the sixteenth century that contains these two poems (and another, “On the Way of the Perfect”): it was copied in Gāzartā and completed on Aug. 10, 1866 AG/962 AH (= 1555 CE). The scribe, named Yawsep, rightly notes in the margin at the beginning of both of these poems that Bar Maʕdani is following Ibn Sīnā on this theme. The latter had written “a treatise, the Bird, an allegory in which he describes his attainment of the knowledge of the truth” (risālat al-ṭayr. marmūza yaṣif fīhā tawaṣṣula-hu ilá ʕilm al-ḥaqq; see Gohlman, pp. 98-99). Here is the marginal note to the first poem, that to the second being much less legible:

CCM 24, f. 112v, marginal note

Bar Sini [sic], the Muslim [hāgārāyā] philosopher, made a treatise [Syr. eggartā = Arb. risāla], the thought of which he somewhere directs to the subject at hand.

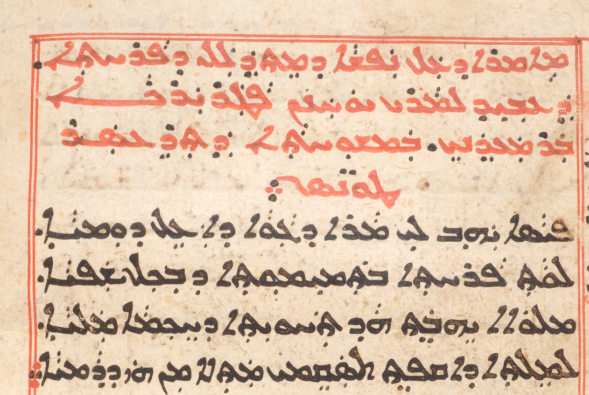

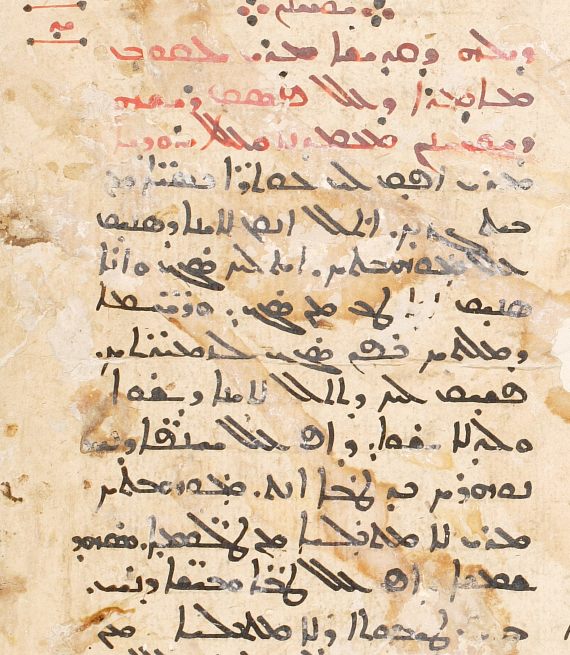

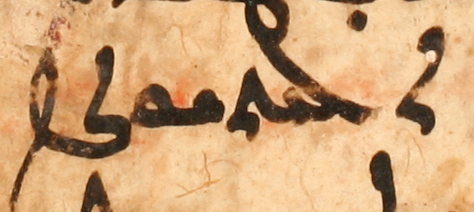

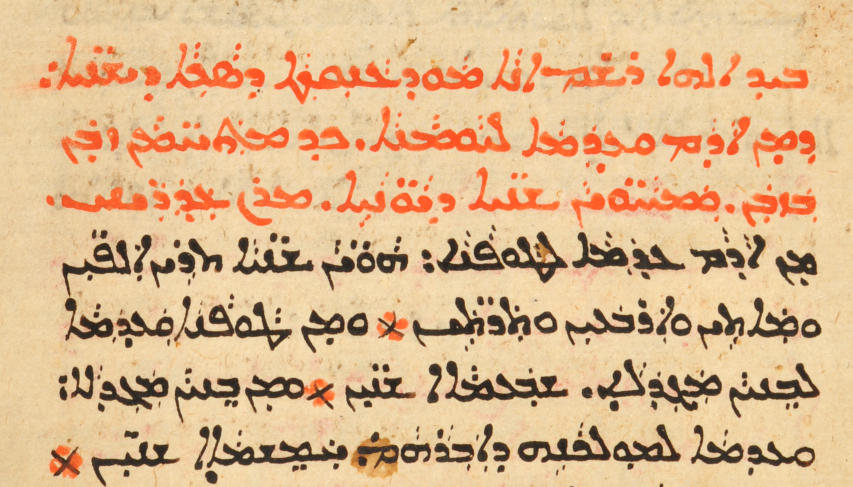

Here are the rubric and first lines of Bar Maʕdani’s first poem on the soul from this manuscript:

CCM 24, f. 112v.

Bibliography (selected!)

Achena, M. and Henri Massé. Le livre de science (Danishnama-yi ‘Ala’i) I: Logique, Métaphysique II: science naturelle, mathématique. Paris, 1986.

Anawati, G. La Métaphysique du Shifa’ I-IV et V-X. Paris, 1978-86.

Furlani, Giuseppe. “Avicenna, Barhebreo, Cartesio.” Rivista degli Studi Orientali 14 (1933): 21-30.

________. ”La psicologia di Barhebreo secondo il libro La Crema della Sapienza.” Rivista degli Studi Orientali 13 (1931-1932): 24-52.

________. “La versione siriaca del Kitâb al-išârât wat-tanbîhât di Avicenna.” Rivista degli Studi Orientali 21 (1945): 89-101.

Goichon, A.-M. “Ibn Sīnā.” In Encylopaedia of Islam, 2d ed., vol. 3, 941-947.

________. Lexique de la langue philosophique d’Avicenne. Paris, 1938.

________. Livre de directives et remarques (al-Isharat wa’l-Tanbihat). 2 vols. Paris, 1951.

Gohlman, William E. The Life of Ibn Sina: A Critical Edition and Annotated Translation. Albany, 1974.

Gutas, Dimitri. Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition. Leiden/Boston, 1988.

Hasse, Dag. Avicenna’s De Anima in the Latin West. London, 2000.

Heath, Peter. Allegory and Philosophy in Avicenna (Ibn Sînâ). Philadelphia, 1992.

Inati, Shams. Ibn Sina on Mysticism (al-Isharat wa’l-Tanbihat namat IX). London, 1998.

________. Remarks and Admonitions Part One: Logic (al-Isharat wa’l-Tanbihat: mantiq). Toronto, 1984.

Janssens, Jules. Bibliography of Works on Ibn Sina. 2 vols. Leiden, 1991-1999.

Janssens, Jules and Daniel de Smet, eds. Avicenna and His Heritage. Leuven, 2001.

Joosse, Nanne Peter. A Syriac Encyclopaedia of Aristotelian Philosophy: Barhebraeus (13th c.), Butyrum Sapientiae, Books of Ethics, Economy, and Politics. Aristoteles Semitico-Latinus 16. Leiden/Boston, 2004.

Mcginnis, Jon. Avicenna, The Physics of The Healing. 2 vols. Provo, 2009.

Marmura, Michael. The Metaphysics of Avicenna (al-Ilahiyyat min Kitab al-Shifa’). Provo, 2004.

________. “Plotting the Course of Avicenna’s Thought.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 111 (1991): 333-42.

Michot, Yahya. “La pandémie avicennienne.” Arabica 40 (1993): 287-344.

Morewedge, Parviz. The Metaphysica of Avicenna (Ilahiyyat-i Danishnama-yi ‘Ala’i). New York, 1972.

Rahman, F. Avicenna’s De Anima (Fi’l-Nafs). London, 1954.

Rashed, Roshdi and Jean Jolivet, eds. Études sur Avicenne. Paris, 1984.

Reisman, D. and Ahmed al-Rahim, eds. Before and After Avicenna. Leiden/Boston, 2003.

N. G. Siraisi, Avicenna in Renaissance Italy: The Canon and Medical Teaching in Italian Universities after 1500. Princeton, 1987.

Takahashi, Hidemi. Aristotelian Meteorology in Syriac: Barhebraeus, Butyrum Sapientiae, Books of Mineralogy and Meteorology. Aristoteles Semitico-Latinus 15. Leiden/Boston, 2004.

________. “The Reception of Ibn Sīnā in Syriac: The Case of Gregory Barhebraeus.”, In Before and After Avicenna (see above), 249-281.

Teule, Herman G.B.”Renaissance, Syriac.” GEDSH 350-351.

________. “The Transmission of Islamic Culture to the World of Syriac Christianity: Barhebreaus’ Translation of Avicenna’s kitâb al-išârât wa l-tanbîhât. First Soundings.” In J.J. van Ginkel, H.L. Murre-van den Berg, and T.M. van Lint, eds. Redefining Christian Identity: Cultural Interaction in the Middle East since the Rise of Islam. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 134. Leuven: Peeters, 2005. Pages 167-184.

________. “Yuḥanon bar Maʿdani.” GEDSH 444.

Watt, John W. Aristotelian Rhetoric in Syriac: Barhebraeus, Butyrum Sapientiae, Book of Rhetoric. Aristoteles Semitico-Latinus 18. Leiden/Boston, 2005.

________, “Graeco-Syriac Tradition and Arabic Philosophy in Bar Hebraeus.” In H.G.B. Teule, C.F. Tauwinkl, R.B. ter Haar Romeny, and J.J. van Ginkel, eds. The Syriac Renaissance. Eastern Christian Studies 9. Leuven/Paris/Walpole, Mass., 2010. Pages 123-133.

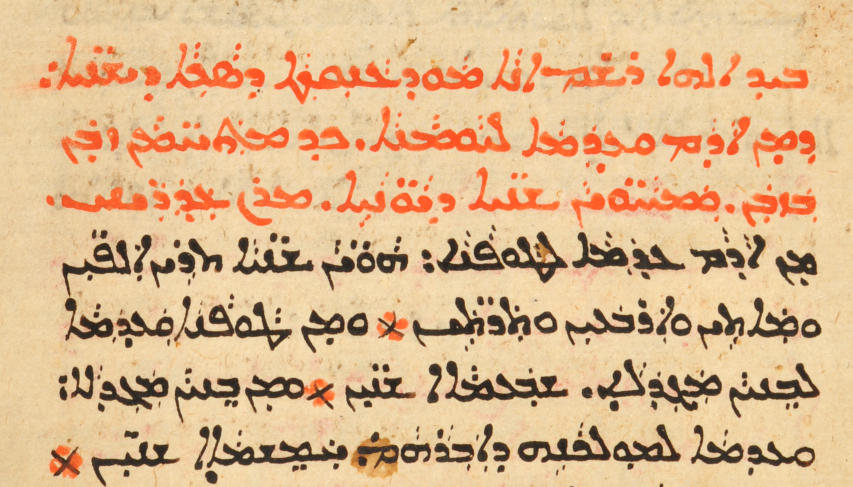

I continue with cataloging the collection of the Chaldean Cathedral of Mardin. In a very important manuscript, some other texts of which I hope to publish in the near future, I’ve come across a short work counting the years from Adam up to the mid-fifteenth century. I’ve just uploaded a document with both the Syriac text and an English translation here, and below just the translation is given.

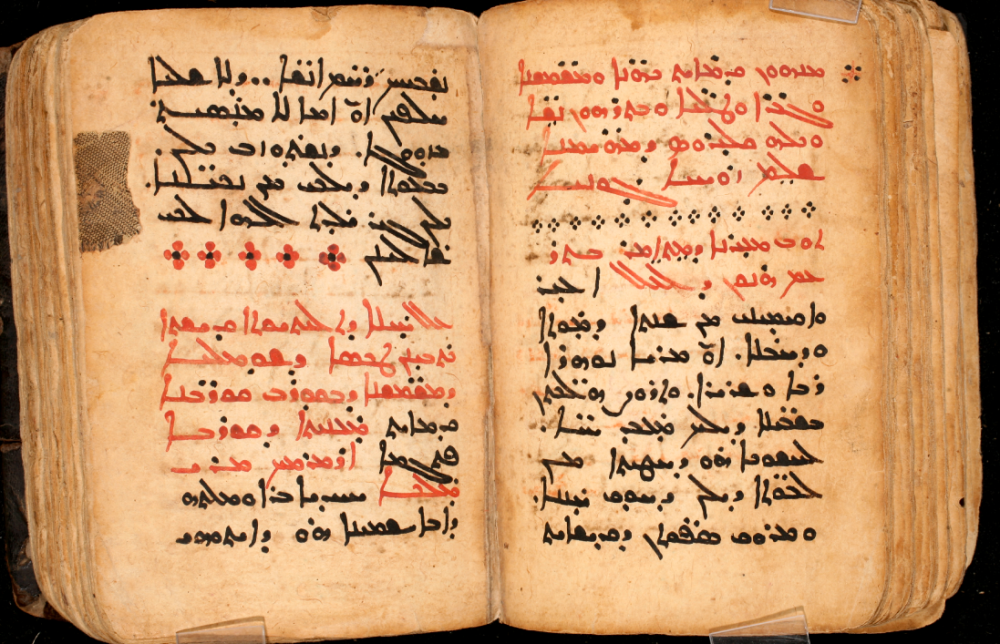

CCM 20, f. 235r

The text comes from an East Syriac manuscript dated to 1770 AG (= 1458/9 CE), Chaldean Cathedral of Mardin (CCM) 20, ff. 235r-235v (olim Diyarbakır 106). Judging from the text itself, it is original to this manuscript (i.e. it’s not a copy). In its details for the years, I have not compared it with other similar texts in Syriac or other languages, but I offer it with an English translation simply as an example of how a fifteenth-century Syriac scribe looked back very briefly across human history as he saw it. In addition, Syriac students might find it to be a short and easy text, especially to practice their knowledge of Syriac numbers.

Translation

With God’s help I note down an index of the sum of years from Adam to today, [the years] sometimes defined, indicating the years of the Greeks. Our Lord, help me!

1 From Adam to the Flood there are 2242 years.

2 From the Flood to the building of the Tower [of Babel], 700 years.

3 From the building of the Tower to the promise [made to] Abraham, 500 years.

4 From the promise [made to] Abraham to the exodus from Egypt, 430 years.

5 [From that time to the time] of Moses, Joshua b. Nun, 67 years.

6 [From that time to the time] the kings, 524 years.

7 [From that time to the time] of the Babylon[ian captivity], 70 years.

8 From the freedom from Babylon to the crucifixion of our savior, 480 years.

9 From the crucifixion of our savior until the Persians ruled, 81 years.

10 From [the time] that the Persians ruled [f. 235v] until the Arabs [ṭayyāyē] ruled, 505 years.

11 From [the time] that the Arabs ruled to the year in which this book was noted down, 862 years.

12 The sum of all the years is 6950 years.

13 The years that the Persians ruled are 550 years.

14 The blessed lady Mary received the good news [i.e. the Annunciation] in the year 303 of the Greeks.

15 Our savior was born in the year 304.

16 He was baptized by John in the year 334.

17 He suffered, died, arose, and ascended to heaven in the year 337 of the Greeks.

18 From the ascension of our Lord to the year in which this book noted down, 1433 years.

Ended is the reckoning and numbering of the years from Adam to the year in which we are.

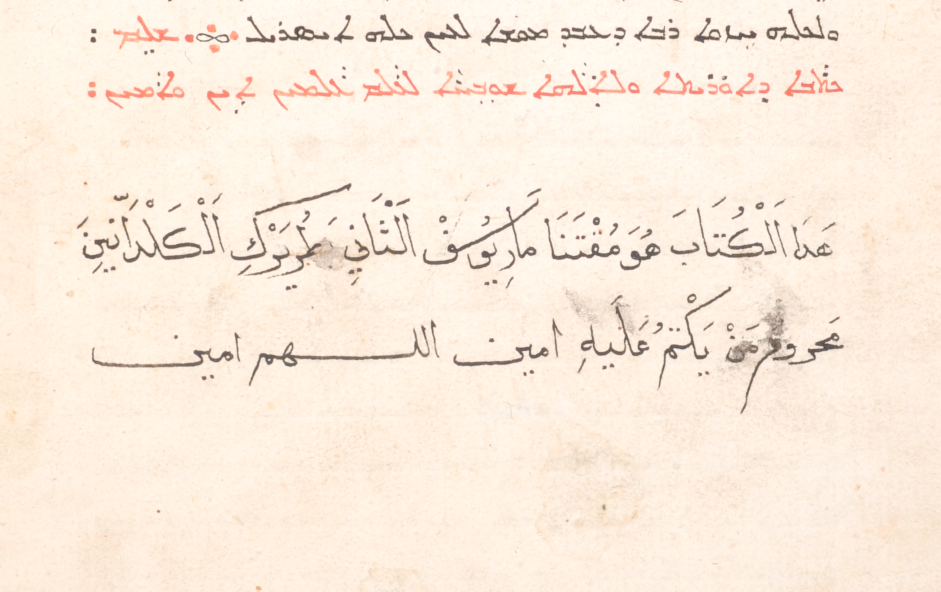

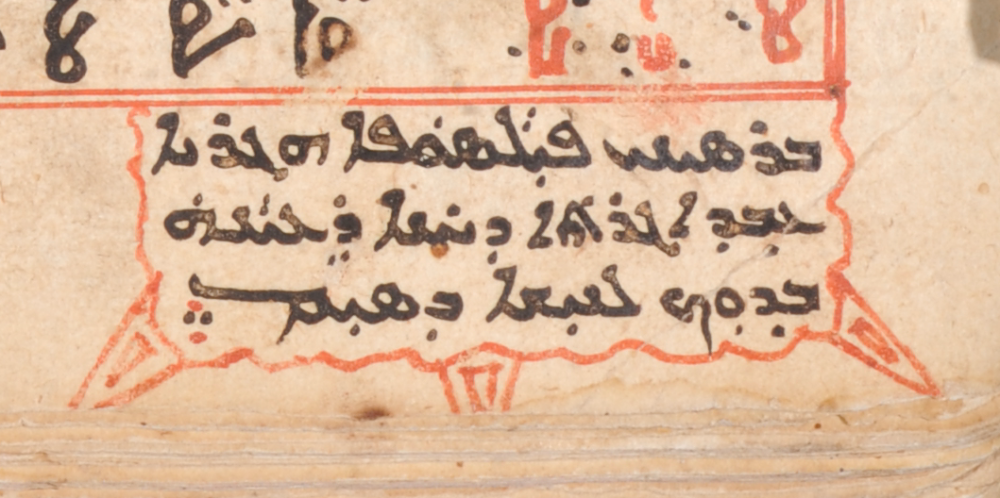

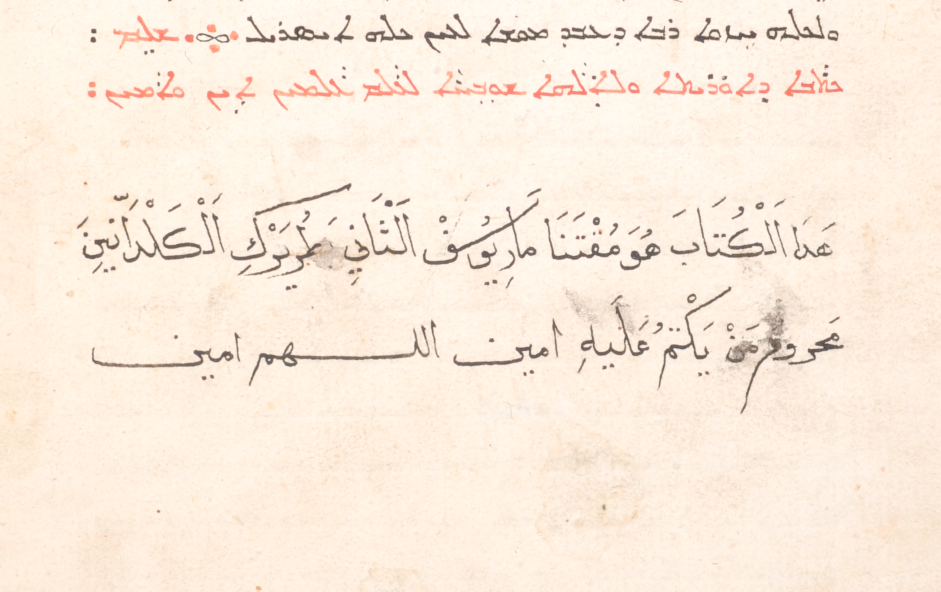

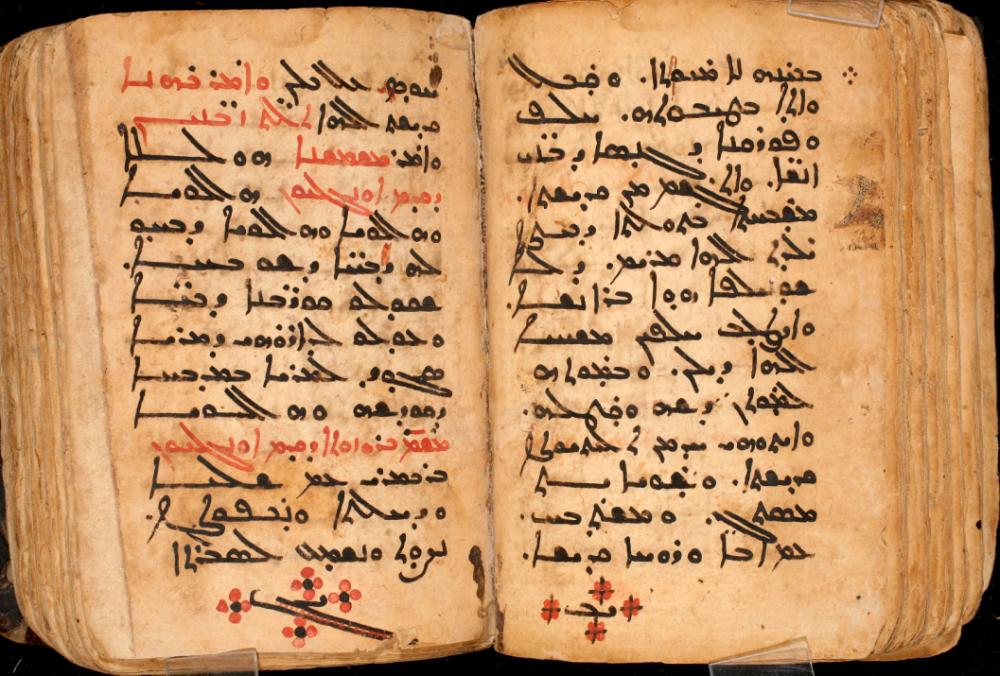

As an addendum to a previous post in which I shared two ownership notes in Syriac for Patr. Yawsep II, here from the same collection is another ownership note, this time in Arabic, and finely written. Like the others, this one also has a curse on any book-thieves. The manuscript is a Syriac Pentateuch — you can see the end of Deuteronomy in the image — in East Syriac script (CCM 40, dated 1651/2).

CCM 40, f. 203v

This book is the property of Mar Yawsep II, Patriarch of the Chaldeans. Whoever conceals it, he is excommunicated! Amen, yes, amen!

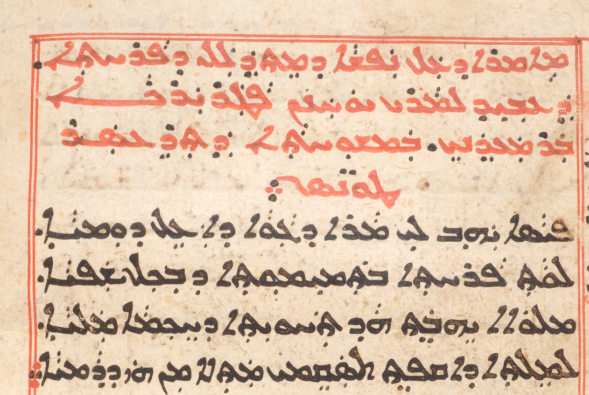

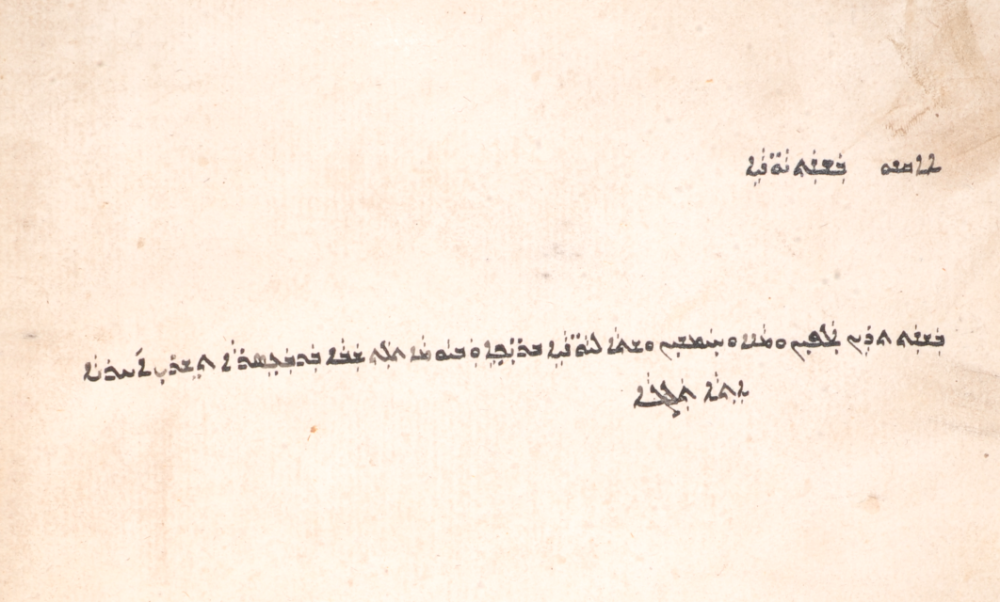

The image below is from the end of CCM 40, a Pentateuch in East Syriac script copied in 1963 AG (= 1651/2 CE). One wonders why the writer of these words was moved to share this meteorological datum here, but here it is in any case, and we’re reminded that every book we look at, whether handwritten or printed, has lived a life before we met it, and other people have often known, read, and marked in that book. Notes like this, as well as colophons and certain other features, make every manuscript unique, no matter how many copies of its text(s) may exist.

CCM 40, f. 206v

In the year 2156 [= 1844 CE] of the blessed Greeks, on Tuesday, on the tenth of Tešri ḥrāyā (November), the snow came.

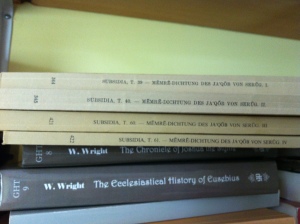

Among the very many contributions of Arthur Vööbus (born in 1909 in Estonia, died 1988), to Syriac studies, most of which touch manuscripts in some way or other, one of his most thorough and still most valuable is the four-volume Handschriftliche Überlieferung der Mēmrē-Dichtung des Jaʿqōb von Serūg (CSCO 344-345, 421-422/Subs. 39-40, 60-61; Louvain, 1973-1980). Jacob of Sarug (or Serugh; ca. 451-521), a prolific luminary of Syriac literature, is especially known for his numerous metrical homilies (mēmrē), the main published collection of which is that edited by the great Paul Bedjan and exquisitely published by Harrassowitz in a fully vocalized East Syriac font (as in Bedjan’s other editions). Still not all of Jacob’s surviving work has been edited, much less translated, but a translation project into English, the results published by Gorgias Press, is underway and hopefully also readers who do not read Syriac will begin to appreciate this author more (subseries Metrical Homilies of Mar Jacob of Sarug, series Texts from Christian Late Antiquity). There are now 304 records on Jacob in the Syriac bibliography of the Hebrew University; on Jacob generally see Brock in GEDSH, 433-435. The aforementioned books by Vööbus, indispensable for any close study of Jacob, present most of what is known concerning the manuscripts — those found in the well-known European collections and those in less accessible places in the Middle East — that have copies of Jacob’s works. Here, as in his other articles and books, we are impressed with the breadth of Vööbus’ manuscript experience and his record-keeping that is in such clear evidence. A perusal of the footnotes in almost any of his contributions reveals a mountain of work never published — how often does he refer to this or that piece “sous presse”, “im Druck”, or “in press” that never appeared? — but into these four volumes he poured years of close attention and study, and every student of Syriac literature is thus in his debt.

Among the very many contributions of Arthur Vööbus (born in 1909 in Estonia, died 1988), to Syriac studies, most of which touch manuscripts in some way or other, one of his most thorough and still most valuable is the four-volume Handschriftliche Überlieferung der Mēmrē-Dichtung des Jaʿqōb von Serūg (CSCO 344-345, 421-422/Subs. 39-40, 60-61; Louvain, 1973-1980). Jacob of Sarug (or Serugh; ca. 451-521), a prolific luminary of Syriac literature, is especially known for his numerous metrical homilies (mēmrē), the main published collection of which is that edited by the great Paul Bedjan and exquisitely published by Harrassowitz in a fully vocalized East Syriac font (as in Bedjan’s other editions). Still not all of Jacob’s surviving work has been edited, much less translated, but a translation project into English, the results published by Gorgias Press, is underway and hopefully also readers who do not read Syriac will begin to appreciate this author more (subseries Metrical Homilies of Mar Jacob of Sarug, series Texts from Christian Late Antiquity). There are now 304 records on Jacob in the Syriac bibliography of the Hebrew University; on Jacob generally see Brock in GEDSH, 433-435. The aforementioned books by Vööbus, indispensable for any close study of Jacob, present most of what is known concerning the manuscripts — those found in the well-known European collections and those in less accessible places in the Middle East — that have copies of Jacob’s works. Here, as in his other articles and books, we are impressed with the breadth of Vööbus’ manuscript experience and his record-keeping that is in such clear evidence. A perusal of the footnotes in almost any of his contributions reveals a mountain of work never published — how often does he refer to this or that piece “sous presse”, “im Druck”, or “in press” that never appeared? — but into these four volumes he poured years of close attention and study, and every student of Syriac literature is thus in his debt.

The work is a whole, but there are clear divisions in it, and not all of the volumes work the same way. There is, naturally, coverage of preliminary considerations at the beginning of vol. 1, and then he turns in that and the next volume to investigate manuscripts more or less particularly dedicated to preserving Jacob’s works (“Sammlungen”), and some of these are indeed hefty with line after line of that poetic bulk. Vols. 3 and 4 focus more on scattered witnesses to Jacob’s work (“Die zerstreuten Mēmrē”), that is, on manuscripts that are not really collections especially of Jacob, but that have one, two, or a few more mēmrē, amid works by other authors. Vols. 1 and 3 provide brief descriptions of the mss, while vols. 2 and 4 list the contents of the mss, with Syriac titles on the left pages, and the title in German translation on the right pages, but unfortunately he gives no incipits, for which, however, we now have Sebastian Brock’s list in vol. 6 of the augmented Gorgias Press reprint of Bedjan’s edition of Jacob’s mēmrē.

Vööbus’ Handschriftliche Überlieferung (HU), then, is obviously a great store of data for Jacob’s poetic œuvre, but it is not always easy to find the information you’re looking for, something I have discovered both while searching for details on a particular mēmrā and while hunting down the mss of particular collections. Something that can be done for each collection is to make a spreadsheet with the appropriate references in it. In its barest form, with shelfmarks and references to vol. and p. of HU, it would thus be useful for anyone with access to a particular collection, but of course the spreadsheet might be expanded to include date, codicological details, contents, bibliography, etc. A significant number of manuscripts for Jacob are present in Mardin in the collection of the Church of the Forty Martyrs (called CFMM at HMML), a massive collection, parts of which were earlier at nearby Dayr al-Zaʿfarān, and here I have made a simple spreadsheet for CFMM mss that Vööbus refers to. (Not all of CFMM has been cataloged at HMML, but much of it has; all of these Jacob mss are available for study at HMML, and copies may be ordered.) Collections of data like this for mss of Jacob’s works might eventually be brought into an open-access online database searchable by contents, date, collection, etc., but for now we must continue to have recourse to these four volumes of Vööbus’ helpful contribution.

Notwithstanding the attention hitherto given to Jacob’s homilies, there remains much work do be done: as mentioned above, not all of the mēmrē have been published, whether by Bedjan or someone else, and really only Vööbus has looked closely at the surviving mss, so that there is not yet a comprehensive picture of how the mss are related. I can say from my work cataloging and from my work in Bedjan’s edition that a new edition is needed, and the more accessible and clear manuscript data is for Jacob’s works, the better prepared the ground will be for that work.

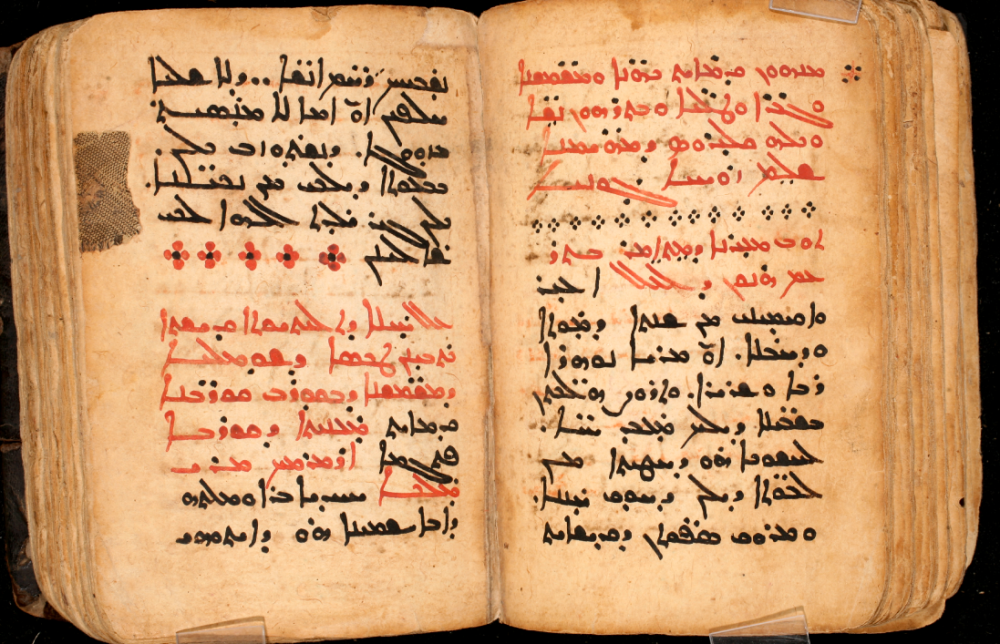

CFMM 132, f. 16r (modern foliation): the beginning of the mēmrā “On the Beheading of John the Baptist” (cf. Bedjan, III 664-687).

In SMMJ 20 (187v), at the end of the Psalms, appears a short hymn on Jesus attributed to Severos. The same text also occurs (probably among others) in DIYR 202, a liturgical manuscript dated 1477, at the beginning of the Rite for the Confirmation of Deacons (77r-78r), but there without any mention of Severos. The handwriting of the latter is more careful, so I give images from that manuscript here.

DIYR 202, ff. 76v-77r

DIYR 202, ff. 77v-78r

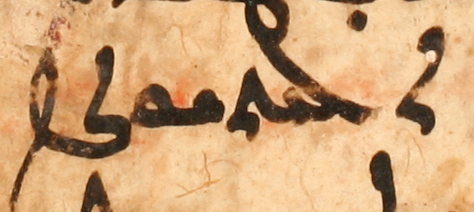

The ending taw-alaf in some cases is written in a unique way that I’ve not noticed before, in which the scribe connects two letters not normally connected.

DIYR 202, f. 77v, line 11 (see also line 5)

It’s not a particularly moving piece, but it’s short and easy, and so it may be a welcome sample for Syriac students to devote a few minutes to.

HMML's copy of the 1636 ed., open to the section corresponding to that shown from the manuscript below.

Church of the Forty Martyrs (Mardin) no. 492, dated Nov 8, 1906, is a late copy of Eliya of Nisibis’ Kitāb al-tarǧamān fī taʿlīm luġat al-suryān (that is, The Book of the Translator, for Instruction in Syriac), his very important Syriac-Arabic lexicon arranged by topic, rather than by the alphabet. The Kitāb al-tarǧamān was published in Rome in 1636 without attribution to Eliya (he is not named in several of the manuscripts either), almost 250 years later by Lagarde (with the Syriac in Hebrew script), and again recently in Iraq. There are a few brief studies on the work, and I discuss it more fully in a paper that has been accepted in the Journal of Semitic Studies, so I’ll not say much more about it generally. Here I only want to highlight the notable manuscript identified above. It is of interest especially for the fact that there is a dedicated slot on every page for Turkish words, even though in many places Syriac and Arabic is all that there is. I have said that there is a “dedicated slot” for Turkish; that is, these words are not merely added in the margin, as in some other manuscripts of Eliya’s book. (In addition to Turkish, Latin and Italian equivalents also show up in some manuscripts.) The image below has the manuscript open to §2.1, with some general vocabulary on humanity and its environment. Syriac is in the right column, Arabic in the center, and Turkish on the left, all written with Syriac letters. The usual arrangement in the manuscripts with only Syriac and Arabic is with the former on the right and the latter on the left (that is, opposite from Obicini’s and Lagarde’s presentations with Syriac following Arabic). It should be noted, too, that this manuscript dates to a time prior to that of the official adoption of a Latin-based alphabet for Turkish, which took place in 1928 as one of Atatürk’s reforms.

CFMM 492, p. 22

Here are the basic meanings listed in this part of the work, along with the Turkish words written according to standard orthography:

- human being insan

- human beings insanlar

- person insan

- people insanlar

- elements aşraf [?!]

- fire ateş

- air, wind rüzgâr

- water su

- earth yer

- mixture mizac

- hot sıcak

- cold soğuk

- wet nem, yaş (note: two words in Turkish, the former really meaning “moisture”, for one in Syriac and Arabic)

- dry kuru

Linguist R.M.W. Dixon has roundly criticized conventional dictionary arrangement, lamenting that, while grammar and other linguistic fields have advanced much in the past few centuries, dictionary-making has not. He recommends, rather than plain alphabetical arrangement, that the order for the lexicon be according to semantic types, and with a kind of index in alphabetical order that points back to this thesaurus. Ten centuries ago, Eliya of Nisibis thought along similar lines for Syriac and Arabic, and some subsequent copyists thought it prudent to tack on other languages (Turkish, Latin, Italian) while tracing this same arrangement.

[Thanks to Reyhan Durmaz for some comments on the Turkish words.]

Bibliography

R.M.W. Dixon, Basic Linguistic Theory, vol. 1, Methodology (Oxford, 2010). See chap. 8, esp. 8.2.

Paul de Lagarde, Praetermissorum libri duo (Göttingen, 1879).

Adam McCollum, “Prolegomena to a New Edition of Eliya of Nisibis’ Kitāb al-tarǧamān fī taʿlīm luġat al-suryān,” Journal of Semitic Studies, forthcoming.

Thomas a Novaria (Obicini), Thesaurus Arabico-Syro-Latinus (Rome, 1636).

Gérard Troupeau, “Le lexique arabe-syriaque d’Elie Bar Shinâyâ,” in J. Hamesse and D. Jacquart (eds.), Lexiques bilingues dans les domaines philosophique et scientifique (Moyen Âge – Renaissance) (Brepols, 2001), 25-30.

Stefan Weninger, “Das ‘Übersetzerbuch’ des Elias von Nisibis (10./11. Jh.) im Zusammenhang der syrischen und

arabischen Lexikographie,” in W. Hüllen, ed., The World in a List of Words (Tübingen: 1994), pp. 55-66.

One of the unendingly amusing parts of colophons (at least those composed by Christians) are the almost grandiloquent means with which scribes tout their now trumpeted humility: gloomy and unfavorable adjective piled upon gloomy and unfavorable adjective, lexical competition with other monastic scribes to find the most picturesque expression for assumed wickedness, &c. A nearly ubiquitous topos goes something like, “…written by the hands of the lowliest of God’s servants, whose name is not worthy to be mentioned…” The scribe nevertheless in most cases goes on to mention his name “on account of the prayers of the brothers”, that is, so that his fellow monk-readers will be able to pray for him (and his family) by name. The scribe of Church of the Forty Martyrs (Mardin) no. 496 (olim Dayr Al-Zaʿfarān 142), an 18th century copy of Bar ʿEbrāyā’s grammatical work called The Book of Splendors (Ktābā d-ṣemḥē), was rather more inventive. In the course of the colophon, written in the dodecasyllabic meter of Jacob of Sarug and with almost every line concluding with the Syriac adverbial ending -āʾit, he says (text in the image below),

If you want to know my name, our brother, read and observe in enlightenment with your great intelligence: Pray to the Lord to grant sincerely in his mercy a good reward to the one who prays lovingly, on whom may the Lord’s mercy be continually.

CFMM 496, p 450

It doesn’t take “great intelligence” to note the rubricated letters in the scribe’s request for prayer. Taking these together, we have the name Ṣlibā, several other examples of which can be found in Wright’s “General Index” to his catalog of the Syriac manuscripts then at the British Museum (p. 1319). While we know no more of his name than Ṣlibā, and that he copied the book in 2026 AG,* we will probably not be mistaken to imagine his having smiled at this playful finishing of his work.

* Also given are 1717 AD and 1127 AH, but these don’t match the AG year exactly.

CFMM 466, f. 296v

Church of the Forty Martyrs (Mardin) ms 466 is a copy of Išoʿ bar ʿAli’s Syriac-Arabic lexicon dated 1857 AG (= 1545/6 CE). The script is a very fine Serṭo — descriptions of scribal hands can tend to sound like you’re talking about wine! — with just the right amount of flourishes for the scribe to show some uniqueness while still making his text simply legible. After the lexicon proper ends, there is a short list (see the image above) of words that have šīn in Syriac but sīn in Arabic, and vice versa; note that a later reader has marked the pair sahrā and šahr with an X, and rightly given the Arabic meaning of sahrā as qamar (“moon”) rather than, strictly speaking, šahr (“month”), although the two sibilant words are surely related, just as “moon” and “month” are in English and other Germanic languages (but not Indo-European more generally).

On the same page as this little comparative list comes the colophon, written sideways, from which we learn both the scribe’s name and the date of copying. Aside from the frequently found terms of scribal self-deprecation, the colophon informs us that ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz completed the work “in a small amount of time in the year 1857 AG in the monastery of the see of Antioch, Dayr Al-Zaʿfarān”, and some of this information is repeated again in a Garšūnī colophon on ff. 300v-301r. This scribe, whose hand penned these lovely letters, was from Mardin, he tells us, specifically the part known as Qāṣur or Qāṣrā (see Payne Smith col. 3708 for references to these toponyms). I was so inspired by the work of ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, that I composed a few humble lines in his honor, to be sung to the tune of Abdul Abulbul Amir:

Of the sons of Mardin there’s scribes and there’s monks,

And many who write in Serṭo.

But of all of those writers, there’s none, I believe,

So precious as ʿAbdulʿazīz!

The note above the colophon is a purchase note in Garšūnī, where we learn that the scribe’s own son, Rabbān Pawlos of Al-Manṣūrīya (from which place we also know a female scribe named Maryam from about the same time period as ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz), bought the book in February of 1886 AG (= 1575 CE) from a certain Rabbān Šemʿon known as Ibn Al-Qarya (?).

CFMM 259, p. 195

This image is of the beginning of Isaac (of Antioch)’s “Homily (Memra) on the Departure (Death) of Children”. The memra begins:

O how bitter is the departure,

How hard and bitter the separation,

That separates a mother from her children,

And a bearer from her beloved ones.

With what voices can we mourn

A beloved, beautiful child,

Who sprouted and grew like a flower,

But quickly withered and vanished?

Most Syriac poets, even Jacob of Sarug, have generally been overshadowed by Ephrem, but lines like these, poignant and emotive, serve as a reminder that there are riches beyond those of Ephrem. (I thought the same recently while reading Qurillona.)

Notice of this homily is recorded in Bickell’s list of incipits (no. 6; in vol. 1 of his ed. of Isaac’s homilies), and according to Sebastian Brock’s list of Isaac’s homilies (JSS 32 [1987]: 279-313), this one is unpublished. There is, however, another memra that begins similarly (no. 177 in Bickell’s list, also included in Brock’s) and that has been published: P. Zingerle, Chrestomathia Syriaca, pp. 387–394 (from Vat. Syr. 92).[1] It turns out that the memra from CFMM 259 above, a text thought to have been unpublished, is in fact not a separate memra from that published in Zingerle’s chrestomathy; it is another version of it with different wording here and there. A comparison even of the short sample given above with the text that Zingerle published shows some of these differences, and there are more. I am not (now, at least) making a full collation, but I note that the reading of CFMM 259 has bearing on Zingerle’s remark on p. 387 about d-pāršā in his text. We are, of course, not unused to the fact of different textual versions, but it is all the easier to get thrown off by the fact when different wording occurs immediately at the beginning of a text!

The manuscript is dated 2220 AG (= 1908/9 CE), and there is a donation note at the beginning dated 1948. A table of contents is supplied at the beginning, but it missed a few of the texts in the manuscript, of which there is a total of thirty. In addition to providing another witness to this homily of Isaac’s, it also contains a number of other notable texts, homiletic, hagiographic (some of which are from Palladios), and apocryphal. Among them:

- Memra on the Cream of Wisdom by John of Manʿim (cf. Barsoum, Scattered Pearls, p. 521)

- The Revelations of the Twelve Apostles, translated from Hebrew into Greek and Greek into Syriac

- The Two Letters that Fell from Heaven (see generally GCAL I 295-296)

- The Story of Sergius Baḥira (text and trans. in B. Roggema, The legend of Sergius Baḥīrā: eastern Christian apologetics and apocalyptic in response to Islam [Brill, 2009].)

- The Story of Maurice the Believing Emperor

- The Story of Taḥsia, the Prostitute that Anba Bessarion Instructed (cf. Bedjan, AMS VII 105-109; also BHO 1137 for Armenian?)

- The Story of Honorios the Emperor

- The Story of Moses the Ethiopian (cf. Bedjan, AMS VII 219-224)

- Memra on Himself, by Bar Qiqi (cf. Scattered Pearls, p. 414)

- The Story of Simeon of the Olives

- The Story of Daniel of Scetis (This text does not seem to exactly match any of those translated by S.P. Brock in T. Vivian, ed., Witness to Holiness: Abba Daniel of Scetis, pp. 181-205.)

- The Story of Daniel of Galaš

- The Story of Mark of Jabal Tarmaq

- Sogitha (dialogue poem) on Joseph and Benjamin (cf. S.P. Brock, Sogyata Mgabbyata [1982], pp. 15-17; cf. Le Muséon 97 (1984): 42.)[2]

The few bibliographic references above are not complete. Some of these texts exist also in other copies at HMML (and elsewhere), either in Syriac or Arabic / Garšūnī.

Notes

[1] Thanks to those members of the Hugoye list who shared copies of Zingerle’s book with me.

[2] Thanks to Kristian Heal for pointing out to me these references for the sogitha.